Chapter 1.

DATING THE NATIVITY OF CHRIST AS THE MIDDLE OF THE XII CENTURY.

3. THE DATING OF THE SHROUD OF TURIN IDEALLY CORRESPONDS WITH THE ASTRONOMICAL DATING OF THE STAR OF BETHLEHEM.

(INDEPENDENT RADIOCARBON DATING OF CHRIST’S LIFE).

3.1. THE DATING.

To recap, the name of the Shroud of Turin is attributed to a piece of linen cloth that survives to this day, in which, it is believed, the body of Jesus Christ was wrapped after the crucifixion.

Let us address a scientific book [163] written by the specialists on the mathematical statistics and concerning the use of statistics in archaeology. With the aid of the method of Bayes estimator, based on one of the radiocarbon measurements of the shroud’s age carried out in Oxford, the authors of the book [163] claim that the linen cloth of which the shroud was made was manufactured between 1050 and 1350 A.D. [163], p.141.

Technically the middle of the XI century would suffice such a dating anyway, but still it is the very end of the confidence interval, which is scarcely probable from the statistic point of view.

If the Star of Bethlehem flared up circa 1140, then Christ’s crucifixion (on the assumption of his age being 30- or 33 years old) should date to the end of the XI century, namely within the interval of 1160-1190. Which is practically in the middle of the above mentioned confidence interval of the radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin: 1050 – 1350. In other words the astronomical dating of the Star of Bethlehem as 1140 wonderfully corresponds with the confidence interval of the radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin. The centre of the latter which is year 1200, which is very close to 1160-1190.

Thus we are getting a wonderful correspondence between the independent radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin and the independent astronomical dating of the Star of Bethlehem.

3.2. THE DETAILS OF THE RADIOCARBON DATING OF THE SHROUD.

In the Scaligerian history the Shroud of Turin is mentioned, for example, under the years of 1350 [165], [180], [47]. It is thought that it was the year when it was shown to the people in the French Mediaeval city of Lirey. This is the earliest from the well documented reports on the Shroud. We would like to note that the Catholic Church knows of several shrouds. But only one of them – the Shroud of Turin – as it turned out, contains a mysterious image, which we will talk about further. We will sometimes call it simply the Shroud. Following various relocations and twists and turns, the Shroud is thought to turn up in Turin in 1578. In a hundred years in 1694 it was placed in the chantry of the Turin Cathedral in a specially made shrine, see fig. 1.13  . The contemporary shrine for preserving the Shroud is shown in fig.1.14

. The contemporary shrine for preserving the Shroud is shown in fig.1.14  .

.

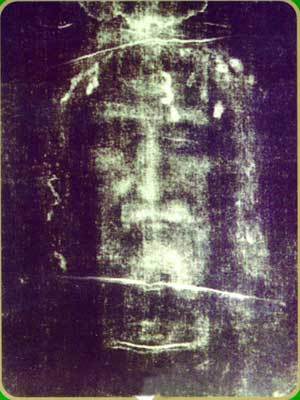

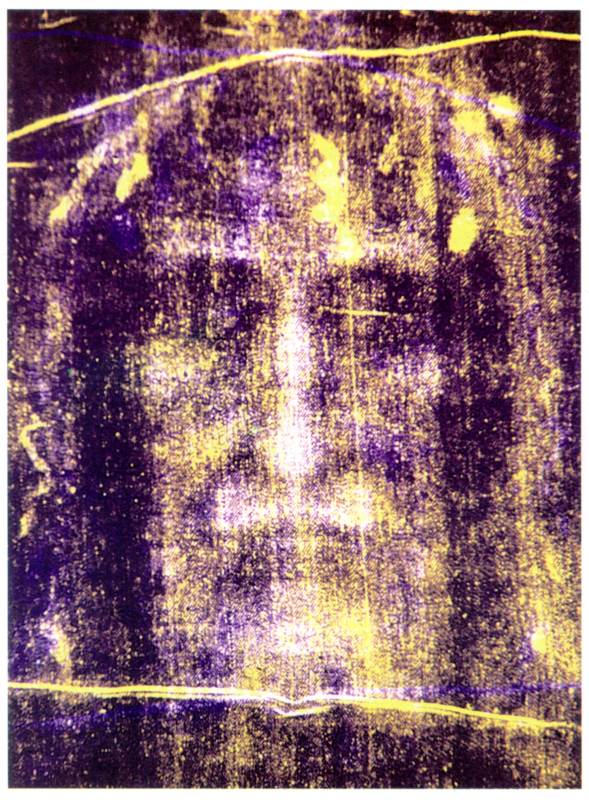

The Shroud of Turin fell under the spotlight following 1898 when a photographer Secundo Pia took the first photographs of it on the instructions of the church authorities [13], [47]. Having developed the photographic plate he discovered with surprise that the negative showed a sharp positive image of a human body from the front and from the back. It appeared that the image of the Shroud was negative. Besides it cannot be seen very well when looking at it without holding up to the light. To remind you, today and already for a long time now, the Shroud was sewn onto another different cloth. This was done to preserve the cloth of the Shroud as it is very thin and quite dilapidated. That is why you cannot look at it against the light and at plain view only some general obscure outline can be seen. The photographic negative however revealed quite a realistic image with various small details.

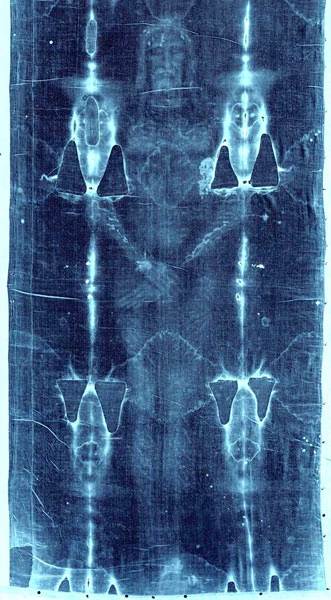

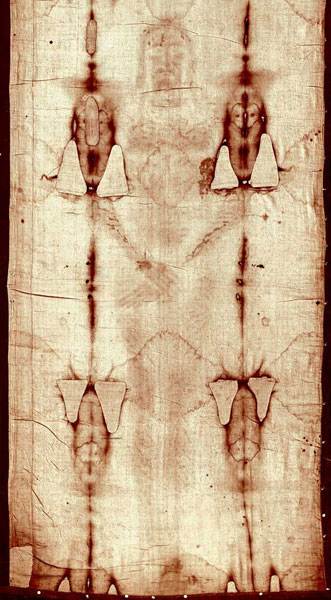

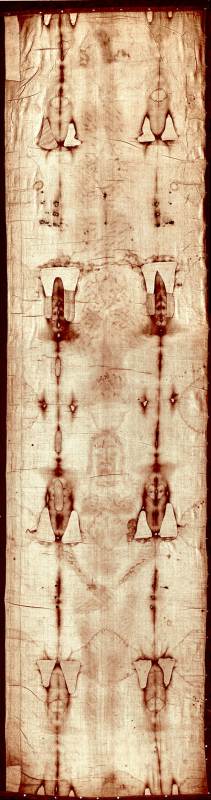

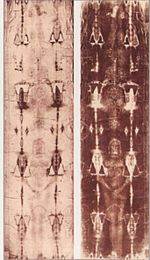

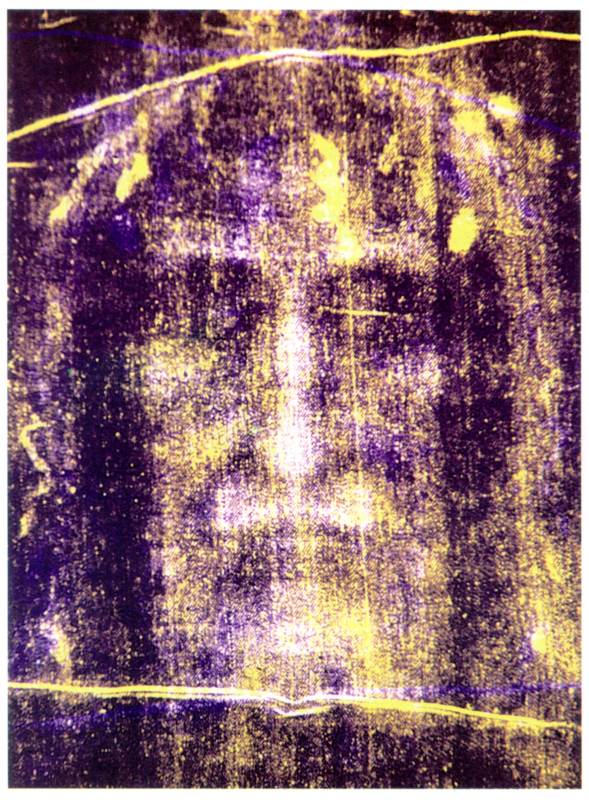

Eventually better quality photographs were taken, see fig.1.15 , fig.1.15a

, fig.1.15a , fig.1.16

, fig.1.16  , fig.1.16a

, fig.1.16a , fig.1.17

, fig.1.17 , fig.1.17a

, fig.1.17a and fig.1.18

and fig.1.18  .

.

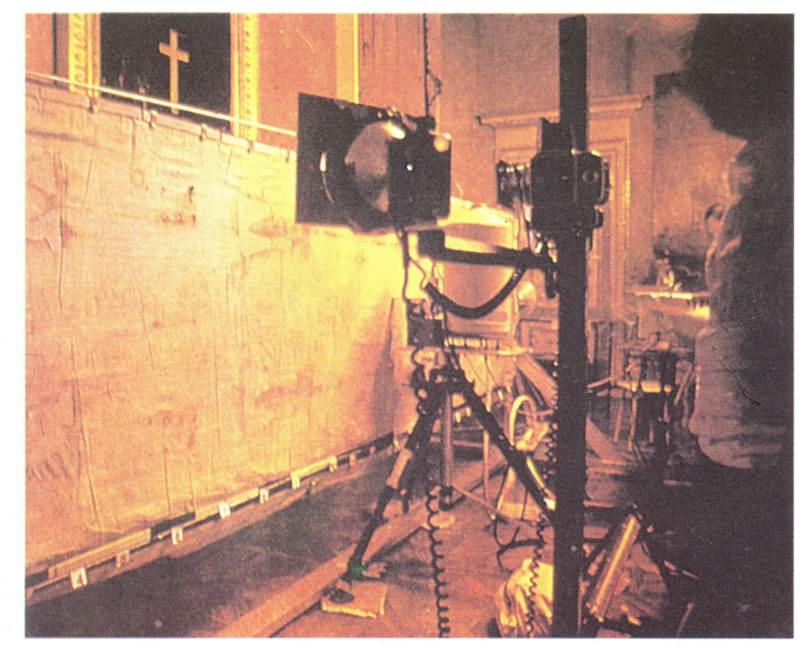

In 1969 for the first time the scientists were allowed access to the Shroud. Earlier the scientific studies of the Shroud were based just on its photographs. Up until 1988 ‘the direct scientific study of the Shroud of Turin was conducted only twice: In 1973 and 1978, and all the conclusions by the scientists on the physical and chemical properties of the cloth, the image and the traces, which are identified as the traces of blood, were based on the results obtained in 1978… There was studied the spectroscopy of the Shroud in a wide range from infrared spectrum to ultraviolet, fluorescence in the x-ray spectrum, there were conducted micro studies and micro photographing including the transmitted and reflected rays (see fig.1.19  – Author). The only objects obtained for the chemical analysis were the finest fibres left on the sticky tape after its dabbing on the Shroud (in fact in 1973 a small piece of the Shroud was after all cut out [165] – Author). The results … can be summed up as follows.

– Author). The only objects obtained for the chemical analysis were the finest fibres left on the sticky tape after its dabbing on the Shroud (in fact in 1973 a small piece of the Shroud was after all cut out [165] – Author). The results … can be summed up as follows.

First of all it was discovered that the image on the Shroud is not a result of the application of any dyes onto the material… the change in the colour of the image was caused by the chemical change of the cellulose molecules, which the material of the Shroud predominantly consists of. The spectroscopy of the cloth in the area of the holy face practically coincides with the spectroscopy of the cloth in the places where it was damaged by the fire… The whole complex of the obtained data informs us that the chemical changes in the structure of the cloth occurred as a result of the reactions of dehydration, oxidizing and disintegration (see fig.1.20  – Author).

– Author).

Secondly, the physical and chemical studies confirmed that the spots on the Shroud were blood. The spectroscopy of these spots is in stark contrast with the spectroscopy in the area of the holy face. It can be seen on the microphotographs, that the traces of blood are left on the Shroud as separate drops, which is different to the consistent discoloration of the cloth in the area of the image. The blood penetrates the depth of the cloth, when the change of the cloth due to the appearance of the image on it occurs only in the thin topmost layer of the Shroud… It was proved that the blood spots appeared on the Shroud before the appearance of the image on it. In those places where the blood remained, it somewhat shielded the cloth from changing its chemical structure. The more refined, but less reliable chemical studies prove that it was human blood of AB group… The intensity of the colour on the Shroud is in a prime functional relationship between the distance between it and the surface of the body. Thus the claim that we have a negative on the Shroud is just the first approach to the truth. Specifically, on the Shroud via the language of the colour intensity the distance between the body and the Shroud is being conveyed…

The problem facing the scientists became the dating of the Shroud as of the XIV century using the radiocarbon method (we will speak about this dating in more detail a little bit further – Author). To explain the dating results there was suggested a hypothesis of changing the isotope abundance of carbon of the Shroud cloth as a result of the nuclear reactions caused by the hard radiation of unknown nature. However the nuclear reactions begin to occur under such high energy under which the cloth of the Shroud becomes completely transparent, and it is impossible to explain the appearance of an image in the upper thin layer around 10 microns thick with such a radiation (therefore there was no mysterious ‘high energy’ here – Author). Consequently there was suggested another explanation: it is conceivable, that the carbon isotope change in the Shroud occurred due to the chemical addition of the ‘younger’ carbon from the atmosphere by the cellulose molecules, which the cloth of the Shroud generally consists of. This could have happened … due to the fire… The building of the cathedral was smoke-logged – the Shroud remained in these conditions for several hours” [13]. See also [47].

However this theory also proved to be insufficient for a substantial shift in the dating of the Shroud backwards, having covered the first centuries A.D. As a matter of fact the effect of absorbing the ‘new’ carbon was discovered, but taking it into account can make the dating older only by not more than 100-150 years [183], p.11-15. The relevant analysis was conducted in the Macromolecular Laboratory (for research on polymers) in Moscow in 1993-1994 (supervisor Dr.Dmitry Kuznetsov) [13]. The studies ‘showed that under the fire conditions cellulose… indeed absorbs carbon from the atmosphere… However shortly the experiments showed, that the volume of the absorbed carbon totals just 10-20 per cent of the amount, which could have changed the dating from the XIV century to the I century [13]. See also [47].

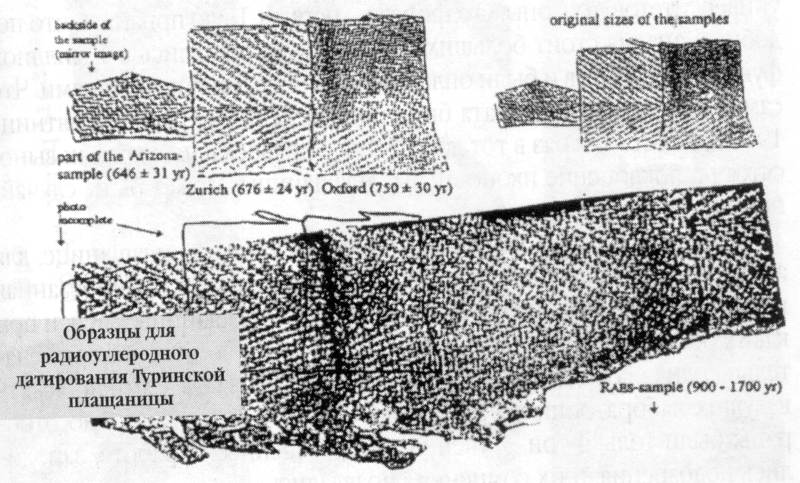

In 1988 the famous radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin was carried out. By that time the methods of the radiocarbon analysis was refined to such an extent that only a small piece of the Shroud was required for the dating. In 1988 a 10 x 70 mm piece was cut off in the bottom left corner of the Shroud. It was then divided into several parts and sent to the three different radiocarbon laboratories – Oxford (England), Arizona (USA) and Zurich (Switzerland). In each laboratory the acquired piece of the Shroud was divided into several parts once again. They underwent various procedures in order to remove any impurities, i.e. pollen, drops of wax, oil, finger prints, etc. Anything that could have got onto the cloth later, over the past centuries, was removed from it [165]. The question whether such procedures could have influenced the radiocarbon dating, generally speaking, is still open, however, significantly different procedures were applied to the different pieces. Therefore most likely there were no artificial shifts in dating in any direction.

Here is the preliminary radiocarbon dating received in all the three laboratories. In other words – this dating was acquired directly from the measurements and did not undergo further ‘calibration’. The fact is that the calibration scale used in such cases is based on the comparison of the radiocarbon dating with the HISTORICAL ones and therefore, generally speaking, is not independent. However, in this case the calibration does not change the dating too much.

The resulting dates were as follows [165]. We cite them in years of A.D., and not in the reverse time scale BP, as it is customary in articles on the radiocarbon analysis. The time scale BP = "before present" counts the dates back from 1950 and does not suit our purposes.

| Arizona: | 1359 plus-minus 30, 1260 plus-minus 35, 1344 plus-minus 41, 1249 plus-minus 33. |

| Oxford: | 1155 plus-minus 65, 1220 plus-minus 45, 1205 plus-minus 55. |

| Zurich: | 1217 plus-minus 61, 1228 plus-minus 56, 1315 plus-minus 57, 1311 plus-minus 45, 1271 plus-minus 51. |

It was exactly these results published in the Nature magazine article [165].

We can see from this table that the boundaries of the measuring accuracy given in it are irrelevant to the confidence interval for the dating of the Shroud, and give only the error estimate of each specific level measuring of the radiocarbon. At the same time the different parts of THE SAME SAMPLE pre-treated using different methods, might give the different shifting in a date, caused by the prior procedures. Besides, to measure the level of the radioactive carbon there were used various methods, which also, generally speaking, could lead to the shifting of the result by unknown variables. In short, besides the error of the definitive measurement, reflected in the table given above – ‘plus-minus a certain amount of years’, - some unknown error enters each measurement the size of which can be roughly estimated by the dispersion of dates. This error appears to be especially great for the measurements in Arizona. Here the dispersion in dates amounts to 110 years. For Oxford – 65 years and for Zurich – 98 years. At the same time when having only 3-4 observations in each case, it is necessary to increase such estimations at least by 2-3 times to evaluate the true accuracy.

So what do the authors of the Nature magazine article do [165]? They average out the dating and their error estimation according to some special methodology by Ward and Wilson used by the archaeologists (Ward G.K., Wilson S.R. Archaeometry 20, 19-31, 1978). Consequently the get a result: 1259 plus-minus 31 years. It is stated that it is a 68% confidence interval, which after ‘calibrating’ using the specific archaeological and historical scale turned into the interval between 1273 and 1288 [165]. For the higher 95% confidence level the ‘calibrated’ date turned out as following: 1262-1384. Respectively, after rounding off: 1260-1390 (with a probability of 95%). Which was frequently and loudly repeated on the pages of the popular world press.

In regards to the calibration, there was used the so called scale of Stuiver-Pearson largely based on dendrochronology and the historical Scaligerian dating. For example, it appears that according to the scale of Stuiver-Pearson several DIFFERENT calibrated dates can correspond to one and the same non-calibrated radiocarbon date! From which the historians are provided with choices and they can choose the ‘correct one' at their own discretion.

A sharp contradiction between the data given in the Nature magazine article and the conclusions based on it catches the eye of any mathematical statistician. A detailed review and critical analysis of the article from ‘Nature’ can be found for example in the articles by Remi Van Haelst) [183]. They give the revised calculations and show that the test results in Arizona form the invariable heterogeneous sample. Besides, based both on the statistical analysis of the data from ‘Nature’ and the information acquired from the private conversations with the specialists who participated in the dating of the Shroud of Turin, Van Haelst make a conclusion, rather plausible from our point of view, that the measurements were slightly ‘pulled up’ towards the middle of the XIV century.

In particular the matter is as follows. Van Haelst mentions the article ‘Natuur en Techiek’ by Dr.Bottema from the University of Groningen in Holland. It states that in Oxford the Shroud of Turin was dated as 1150 A.D. The article cited a photograph of the sample of the Shroud examined in Oxford, which was not published before then. In Van Haelst’s opinion it meant that Dr.Bottema had received some ‘secret information’ on the dating of the Shroud from a former member of the Oxford team. Thus the main point of Van Haelst’s criticism (not just in the case with Oxford, but also with both Arizona and Zurich) can be summarised as the fact that the date of the TWELFTH century was attempted to be ‘pulled up’ to the fourteenth century. Let us clarify why it was done.

From the ‘historical point of view’ the appropriate dating for the Shroud could be either the I century (i.e. the epoch of Christ according to the Scaligerian chronology) or the XIV century, when, as it was said before, the Shroud was exhibited for the first time in Western Europe. Let us stress that the last date was taken again from the very same Scaligerian chronology. In the first case the historians would claim that the Shroud was an original and the body of the crucified Christ was in indeed wrapped into it. In the second case – i.e. if the dating was the XIV century – they would state just as well that the Shroud is an ingenious fake made exactly in the XIV century. And consequently they would suggest the following reconstruction obvious to everyone. It is clear, they would say, that such an amazing fake should have become so famous. It would have been shown to the people straight away, but not kept under wraps for three hundred years somewhere. In fact, that’s exactly the way it is! You see, the Shroud is mentioned in the chronicles of precisely the XIV century (dating according to Scaliger). A complete match with the radiocarbon dating! Thus in both cases the Scaligerian chronology would have been ‘successfully confirmed’. So the historians would have been happy with either variant. But in any other case there would have appeared a contradiction with the Scaligerian version. And the historians did not want that.

However the very first radiocarbon measurements of a sample from the Shroud conducted in Arizona clearly showed, that it is impossible to date the Shroud as the I century A.D. But the acquired dates ‘did not fit’ the XIV century either. As we saw in [183] in fact it appeared to be the XII century. This caused bewilderment. The following way out was found. As the XII century is not that far from the XIV century, taking into account possible errors and acceptable stretches, then, after considering the matter, it was decided to ‘pull up’ the desired date to the XIV century (it was unfeasible to pull it up towards the I century). We’ll repeat that the problem most likely lay in the fact that the initially acquired radiocarbon dating of the twelfth century looked ‘wrong’ from the historical point of view. Which would cast a shadow either upon the Scaligerian history, or the accuracy of the radiocarbon method. None of it was desirable.

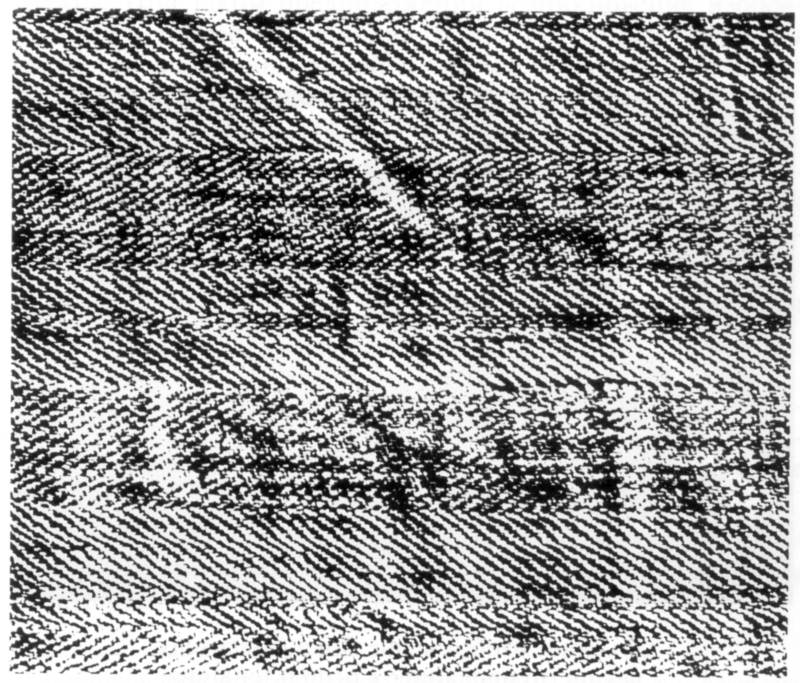

The analysis of the scientific articles dedicated to the radiocarbon dating of the Shroud, among other things, dispels the widespread myth that the three laboratories independently worked with the samples of the Shroud ‘in the dark’. I.e. not knowing which of the several reference samples they had been presented with was in fact taken from the Shroud and which were not. The truth is, that the particulars of the fabric of the Shroud – weaving (see fig.1.21  , fig.1.22

, fig.1.22  ), colour, etc. – were widely and well known. There were countless discussions in press. Therefore in order to make the samples truly unrecognisable they should have been reduced to fragments, cut into tiny pieces. And instead of a piece of cloth they should have sent to the laboratories sort of strands of thread. Such a possibility was discussed, but was declined. As this could have reduced the accuracy of the radiocarbon dating [165]. A decision was made to send off the samples whole, see fig.1.23

), colour, etc. – were widely and well known. There were countless discussions in press. Therefore in order to make the samples truly unrecognisable they should have been reduced to fragments, cut into tiny pieces. And instead of a piece of cloth they should have sent to the laboratories sort of strands of thread. Such a possibility was discussed, but was declined. As this could have reduced the accuracy of the radiocarbon dating [165]. A decision was made to send off the samples whole, see fig.1.23  . Realising that in the laboratories they would very well understand which of the sent samples was the fragment of the Shroud. So they enthusiastically described ‘sealing in the foil’ and ‘encoding of the samples’ – all of this is just promotional showcasing. Though truth be told they say the employees who were actually providing evaluation, apparently ‘did not know’ which of the samples was taken from the Shroud and which was not. So they suggest that we should think, that the laboratory management decided to test the qualification level of their own members of staff in the situation where an ‘incorrect’ result could have considerably harmed the reputation of the facility. It is difficult to believe in such a version of the events.

. Realising that in the laboratories they would very well understand which of the sent samples was the fragment of the Shroud. So they enthusiastically described ‘sealing in the foil’ and ‘encoding of the samples’ – all of this is just promotional showcasing. Though truth be told they say the employees who were actually providing evaluation, apparently ‘did not know’ which of the samples was taken from the Shroud and which was not. So they suggest that we should think, that the laboratory management decided to test the qualification level of their own members of staff in the situation where an ‘incorrect’ result could have considerably harmed the reputation of the facility. It is difficult to believe in such a version of the events.

To clarify, besides the fragments of the Shroud each laboratory was given three more samples [165].

1) A piece of linen from the Egyptian tomb at Qasr Ibrim in Namibia. The tomb was discovered in 1964. It was dated by the historians and the archaeologists. Specifically, based on the Islamic embroidered pattern and the Christian ink inscriptions the given linen fabric, as the tomb on the whole, was dated to the XI-XII cc. A.D.

2) A piece of linen from the collection of the Department of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum. This linen was taken from the mummy of ‘Cleopatra from Thebes’ and was dated by the staff of the British Museum as the beginning of the II century A.D.

3) Threads removed from the robe of St.Louis d’Anjou which is held in the Basilica of Saint Maximin, Var, in France. On the basis of the ‘stylistic details and historical evidence’ it was dated by the historians to 1290-1310.

Oxford, Arizona and Zurich LABORATORIES WERE INFORMED IN ADVANCE of all the three specified dates ‘established’ by the historians [165]. Usually this significant fact is hushed up. Thus the PHYSICISTS WERE INFORMED IN ADVANCE OF THE RESULT for the three ‘references samples’. Needless to say, the laboratories successfully ‘confirmed’ it.

Here, consequently, we come across a TYPICAL PRACTICE in the matter of the radiocarbon dating of the archaeological samples. The historical items and samples are usually sent to the radiocarbon laboratories accompanied by the provisional date sought by the historians. I.e. the archaeologists inform the physicists of the answer they need from them. The only thing left for physicists to do is to ‘scientifically verify’ the date provisionally acquired by the archaeologists. That is exactly what they do choosing from the obtained spectrum of the widely scattered radiocarbon dates only those, closest to the ‘required historical’ ones. Thus the physicists ‘approve’ of the Scaligerian history and the historians ‘help’ the physicists not to ‘make a mistake’. Unfortunately the practice is exactly like this.

But this most likely means, that in the case with the Shroud of Turin the dating of the ‘reference’ samples was carried out only for appearances, for publicity purposes. As the physicists already knew the ‘correct’ age in advance. They only didn’t not know the age of the Shroud. But as we saw earlier there existed two most desirable ‘dates’ of the Shroud for the historians: either the I century (then allegedly it was the original) or the XIV century (then, they say, it’s a fake). The other dates were ‘considerably worse’. Most likely the physicists knew this.

We would like to note that the laboratory measurements themselves were conducted in all likelihood with the due diligence and with sufficient care. The stretches appeared mainly at the stage of the interpretation of the results, their ‘calibration’, adjustment, etc.

CONCLUSION. Based on the radiocarbon dating of the Shroud in the laboratories of Oxford, Arizona and Zurich, it is possible to reach a conclusion that the DESIRED DATE OF THE MAKING OF THE SHROUD MOST PROBABLY LIES BETWEEN 1090 AND 1390. These are the end points of the obtained intervals of dating inclusive of the possible errors in measurements. Most probable is the dating interval by Oxford as it has the lowest variation. Namely from the 1090 to 1265. THE DATING OF THE SHROUD TO THE I CENTURY IS IMPOSSIBLE. All the experts concur with that [165], [183].

The obtaining of the exact confidence interval in the described situation appears to be problematic, as the nature of errors, causing such a considerable scatter of separate dating in each of the laboratories, is unclear. This being said the selection is not that big: 4 measurements in Arizona, 3 in Oxford and 5 in Zurich. The measurements carried out in Arizona are admittedly patchy and it is not statistically justifiable to join them into one selection. The Oxford measurements (there are three of them) and the Zurich ones with the least probability (there are five of them) can be considered to be homogeneous.

As a result we obtain another independent confirmation, that the star which flared up in the middle of the XII century in the place of the Crab Nebula is indeed the Star of Bethlehem. If the star flared up circa 1150, then the Crucifixion should have been taken place at the end of the XII century, in 30-40 years. And in fact, the end of the XII century is covered well by the interval of the radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin.

3.3.’THE COMMON’ RADIOCARBON DATING OF THE HISTORICAL MONUMENTS.

A question might arise: why, while not trusting the radiocarbon dating on the whole, see the details in [MET1] and CHRON1, ch.1:15, we, nevertheless, describe in such detail the radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin. The answer is as follows. Certainly, the radioactive method is highly inaccurate. Various reasons, which are not fully determined yet, might influence it. However, if required, it is still possible to use for dating. Subject to rigid following of the scientific norms and scrupulous evaluation of accuracy. In reality nothing of the kind is being done, see [MET1] and CHRON1, ch.1:15. The dating of the Shroud of Turin is the rarest exception. The typical practice, as we have already said, consists of the following. An archaeologist having recovered from the ground some samples sends them to the physics laboratory for radiocarbon dating. But not just like that, he also provides his findings with the approximate dates received on ‘historical grounds’. Thus the archaeologist actually in advance informs the physicists of the answer he would want to receive. If he really sincerely wanted to learn the true age of the findings, he should have sent several (preferably dozens) of samples of the very same layer to DIFFERENT laboratories WITHOUT PRELIMINARY DATES. And then compare the received results. But usually none of this is done. The physicists in their turn, having received ‘the historically correct answer’ in advance, most likely chose from the greatly scattered radiocarbon dating the one, which corresponds with it best. Thus it results in a vicious circle.

3.4. THE SUDARIUM (NOT-MADE-BY-HAND IMAGE OF OUR SAVIOUR) AND THE SHROUD.

The researchers have noticed long ago that the Shroud can be traced back well in Western European history, but not in the history of the Eastern-European countries. Though, as it’s widely thought, it was brought from Constantinople, i.e. from the East. It is strange, that in the history of the Eastern Church there is almost no information about Christ’s Shroud. Some might object that in every Russian church there is a Shroud of its own and there specific ceremonies connected with it. Which exist only in the Russian church – they do not have them in the West. It is true. But there no legends about Christ’s Shroud itself in Russia today – where it was kept, whom and when it was shown to, etc. On the other hand, both in Byzantine and in Russia ‘another relic is well known and revered – Not–Made-by-Hand Image or Mandylion in Greek (from the Arabic ‘sudarium’) from Edessa (Holy Mandylion of Edessa). In Russian it secured ‘[13] the name of ‘Ubrus’ (Sudarium). Many researchers had long come to conclusion that UBRUS AND SHROUD IS THE VERY SAME OBJECT. We would like to note, that the word ‘Ubrus’ in the Old Russian language apparently meant the same thing as the shroud, i.e. a scarf, a towel, etc. I.e. a wide long piece of cloth [41], [42], [43].

A question may arise – why do we see on the Shroud the depiction of Christ in full length, but on the Sudarium - only his holy face? The answer is most likely as follows. The Shroud was kept folded in a way, so that the visible part can show only Christ’s holy face. And there is an indirect explanation to this.

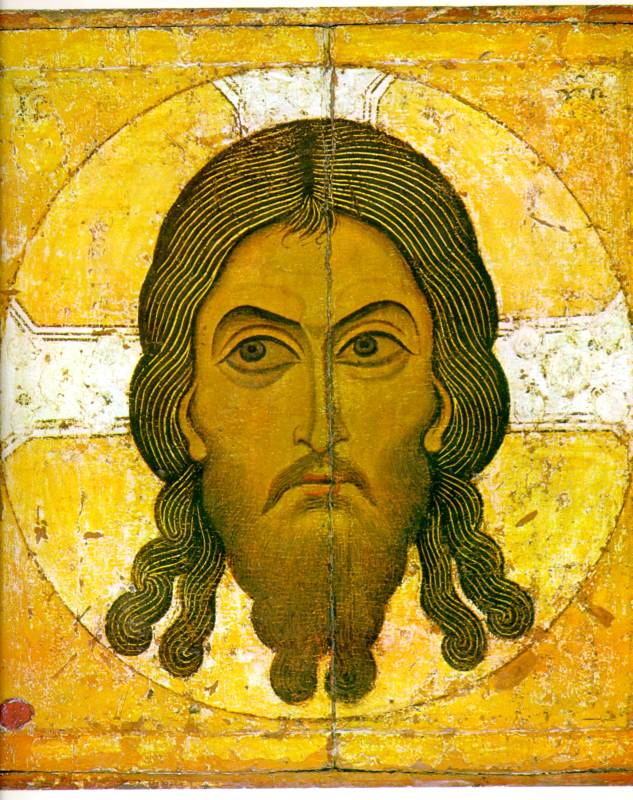

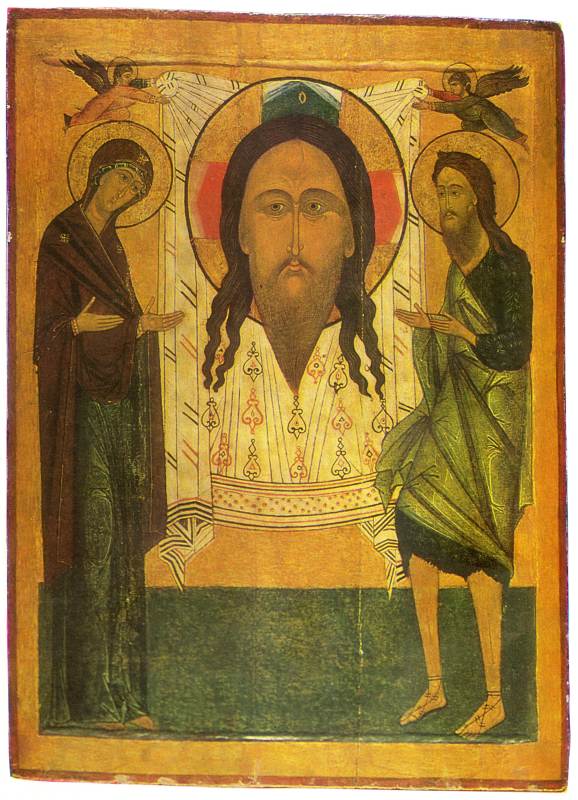

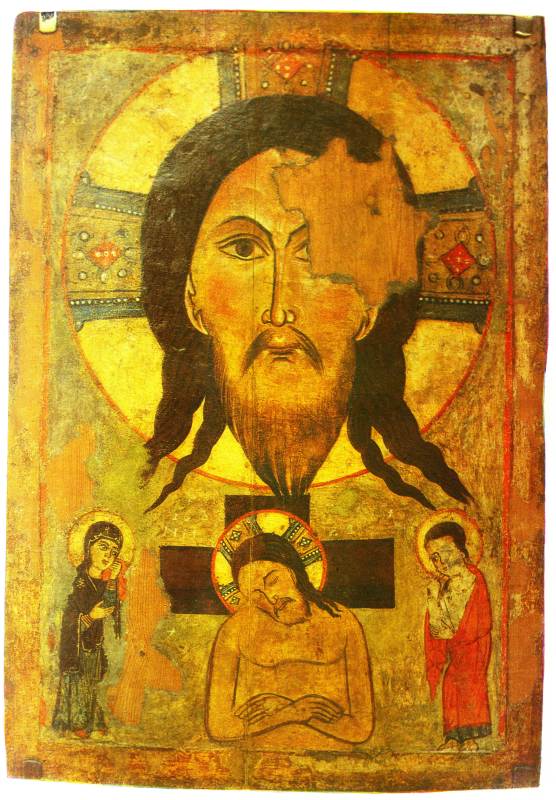

It appears, that the Image Not-Made-by-Hand or Sudarium ‘was also called by another Greek word TETRADIPLON. The meaning of this - word is ‘folded four times’ - was unclear. If we address the Shroud of Turin, then the meaning of this name will become clear. In the wake of the fire… we can determine, that the four meter Shroud was folded four times in such a way, so that the holy face was in the centre and on the surface of the folded Shroud’ [13].’ Also see [47]. So we can see, that looking at the former folding lines surviving on the Shroud it is possible to learn, that the Shroud was kept in such a way, that only the image of the holy face of Christ was visible. I.e. Image Not-Made-by-Hand. Which is so WELL-KNOWN IN RUSSIA. It is depicted in every Russian church, an important celebration in the Russian church is devoted to it. Icon of Christ, Our Saviour Not Made By Hand is one of the most well-known icons in Russia, see, for example, fig.1.24  . We present two more Russian icons depicting Christ, Our Saviour c in fig.1.25

. We present two more Russian icons depicting Christ, Our Saviour c in fig.1.25  and fig.1.26

and fig.1.26  .

.

We should pay attention to Christ’s hair in the image of the Saviour Not-Made-by-Hand that is depicted braided and falling on the shoulders to the left and to the right. But then Christ’s hair as depicted on the Shroud of Turin also lies in long strands and falls on his shoulders. For example, Giovanni Novelli notes: ’On the Shroud there is depicted a bearded man. His hair is long, FORM A KNOT AT THE BACK, AS IF FROM A DISHEVELLED BRAID’ [47], p.11. It could be, that this particular characteristic of depicting Christ – braided hair – reflected the reality.

From the point of view of the new chronology the story of the Shroud of Turin, i.e. the Not-Made-by-Hand Holy Image, most probably, looked like this. Most likely the Shroud = Not-Made-by-Hand Holy Image originates from the XII century. I.e. IS THE ORIGINAL. It is that very Shroud, which the body of Christ was enveloped in in 1185 A.D. (more detail about this date will follow further). Then after some time it turned up in Russia. There it was held folded so that on its surface only the holy face, which was depicted on many Russian icons, was visible. As the Shroud was located in Russia, the icons of the Holy Image Not-Made-by-Hand were mainly painted by the Russian artists. In the West such images were quite rare. The Western artists imagined the story of the Shroud somewhat differently. See, for example, the A.Durer engraving in fig.1.27  . In Russia the icon of the Saviour Not-Made-by-Hand (The Icon of Christ of Edessa) was also used as a military holy banner. We quote: ‘Such Icon of the Saviour adorned the banners of Yaroslav, Tver’ and Moscow princes, acted as the defender of the Russian land and protector of the Russian army. Under its banners the Battle of Kulikovo took place’ [63], p.97.

. In Russia the icon of the Saviour Not-Made-by-Hand (The Icon of Christ of Edessa) was also used as a military holy banner. We quote: ‘Such Icon of the Saviour adorned the banners of Yaroslav, Tver’ and Moscow princes, acted as the defender of the Russian land and protector of the Russian army. Under its banners the Battle of Kulikovo took place’ [63], p.97.

As the Shroud was held in Russia it becomes clear why it was exactly there that a particular ceremony of the Adoration of the Holy Shroud during the Holy Week originated. It is entirely absent in the Catholic Church [13]. This church ceremony involves carrying the Shroud out of the church and the religious procession with it in the evening on Good Friday. But most likely the real Shroud was not usually disturbed. Instead of the original its many copies kept in each church were used. The original of the Shroud, judging by the folds on it, was carefully preserved folded up. So that only the holy face of Christ was visible. That is why it was called the Not-Made-by-Hand Image or the Sudarium (Vernicle). During the Time of Troubles at the beginning of the XVII century, when Moscow treasures were ransacked in the atmosphere of the rebellion and occupation, many things found themselves in the West. Including, among other things, the Shroud which was moved away. It is quite probable that it was in XVII century that the Shroud found itself in a fire and burnt through in several places. The traces of the fire can be seen even today. The usual suggestion is that of the fire in Savoy in 1532 [180] which is only a hypothesis by the scientists. The same as the hypothesis that the Shroud emerged in Turin in Italy in 1578.

It is possible that there was some kind of Shroud in Turin. As there are several of the alleged shrouds known in the West. But the present Shroud emerged in Turin, according to our opinion, ONLY IN THE XVII CENTURY. In fact it is known that it was housed in a special shrine and placed in the cathedral of the city of Turin ONLY IN 1694 [165]. In relation to the new chronology this date – the end of the XVII century – speaks volumes. It was then, after crushing Razin and after the Turkish defeat at the Battle of Vienna, when it became clear, that the time of the Great Empire becomes a thing of the past. Russia-Horde was to be feared no longer. It was possible at last to bring from the coffers into the daylight the seized treasures and sacred relics. Including the Shroud. Not fearing that the former owners would return and reclaim everything.

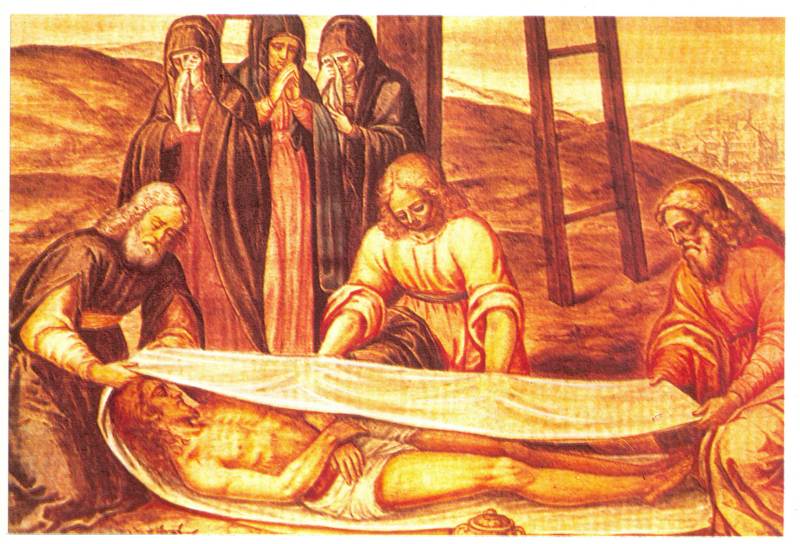

In fig.1.28  there is presented an old image ‘The Holy shroud from the Sabauda Gallery’ – watercolour on silk ‘originally attributed to Dalmatian miniaturist Giulio Clovio(1498-1578), but eventually it emerged that its author Giovanni Battista della Rovere created it most probably between 1623 and 1630 being inspired by a theory concerning the formation of the image created by Emanuele Filiberto Pingone, the historiographer of the House of Savoy, presented by him in his book ‘Sindon’’ [47], p.2. it is understandable why this water-colour was created exactly in the XVII century. As we already said, it was in the epoch of the Time of Troubles that the Shroud most likely was moved out from Russia to Western Europe.

there is presented an old image ‘The Holy shroud from the Sabauda Gallery’ – watercolour on silk ‘originally attributed to Dalmatian miniaturist Giulio Clovio(1498-1578), but eventually it emerged that its author Giovanni Battista della Rovere created it most probably between 1623 and 1630 being inspired by a theory concerning the formation of the image created by Emanuele Filiberto Pingone, the historiographer of the House of Savoy, presented by him in his book ‘Sindon’’ [47], p.2. it is understandable why this water-colour was created exactly in the XVII century. As we already said, it was in the epoch of the Time of Troubles that the Shroud most likely was moved out from Russia to Western Europe.

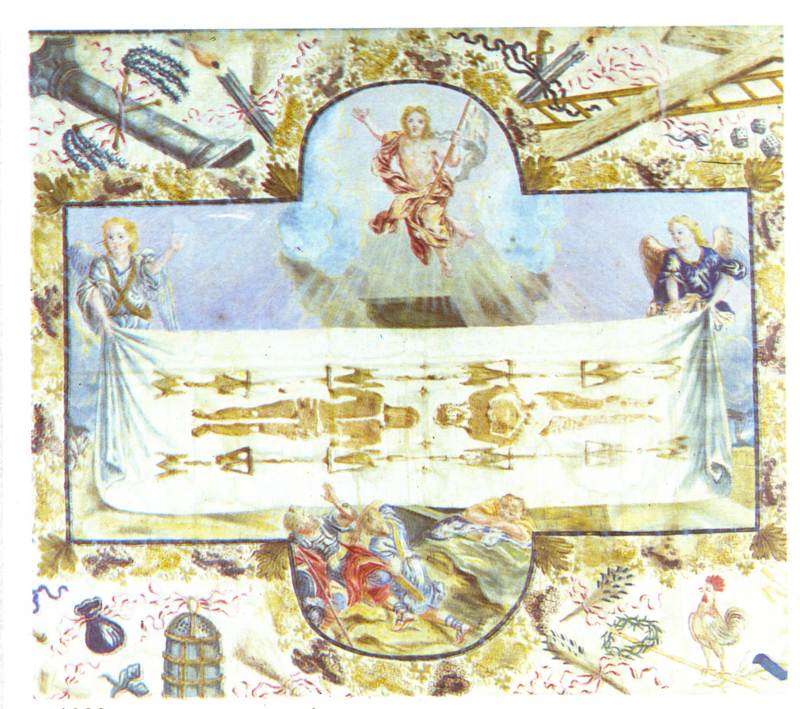

In fig.1.29  is presented another Western European depiction of the Shroud dated to XVII century. Here the artist portrayed a double imprint of Christ’s body, as on the Shroud of Turin.

is presented another Western European depiction of the Shroud dated to XVII century. Here the artist portrayed a double imprint of Christ’s body, as on the Shroud of Turin.

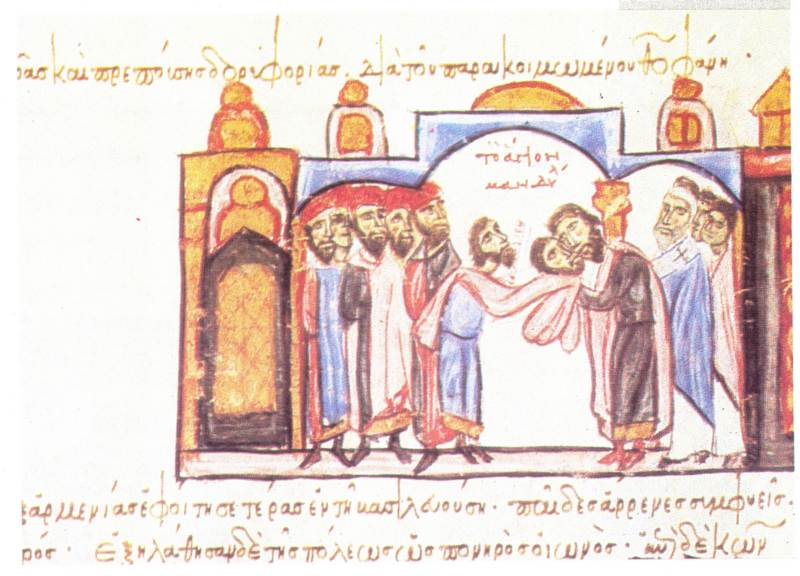

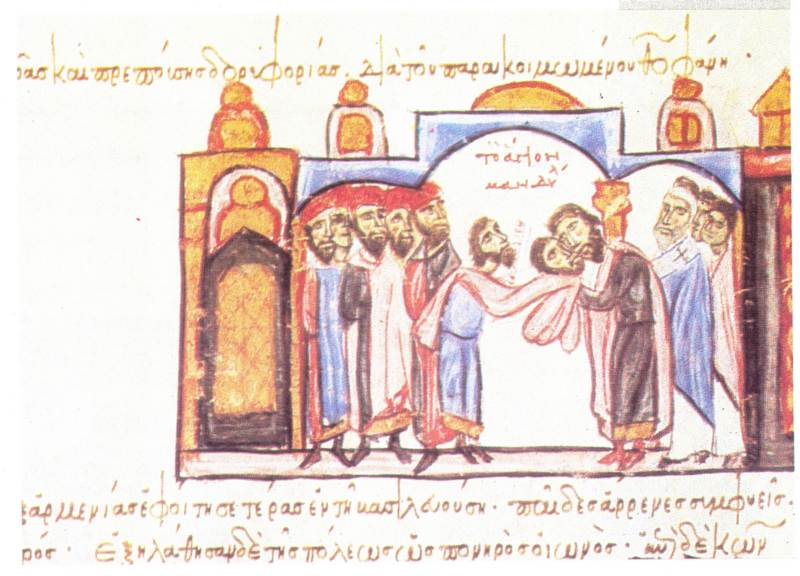

In fig.1.30  is presented a miniature of allegedly the XIII century showing the ‘return of the Holy Shroud to Constantinople (allegedly in 944 – Author)… In the beginning of the iconoclastic period (allegedly in 726 – Author) the Shroud was carried to Edessa. Here is shown the moment of passing it over to the Byzantine emperor Roman I Lakapin [47�], p.16.

is presented a miniature of allegedly the XIII century showing the ‘return of the Holy Shroud to Constantinople (allegedly in 944 – Author)… In the beginning of the iconoclastic period (allegedly in 726 – Author) the Shroud was carried to Edessa. Here is shown the moment of passing it over to the Byzantine emperor Roman I Lakapin [47�], p.16.

However, in the old manuscript itself the name of the emperor is by no means Roman Lakapin. According to one interpretation it reads (‘Lazapen’[47], p.9, according to another – ‘Laoesn’ or ‘Laoese’,see the photograph of the manuscript in [47a], p.16. The last one reminds us of the name of Theodore Lascaris, the famous emperor of the XIII century, the founder of the Empire of Nicaea. The name LASCARIS, i.e. LAS-CARIS, LAS-CIR might stand for CZAR LAS or CZAR LAOES. We’ll point out that the time of ruling of Theodore Lascaris - the first half of the XIII century – perfectly corresponds to the dating of Christ’s life to the XII century. It is most likely that it was in the XIII century when the Shroud was returned to Constantinople. It has disappeared from there possibly not long before then – during the infamous sacking of Czar-Grad by the Crusaders in 1204 [117]. When, as it is well known, a large amount of Christian relics were carried away.

Let us get back to the miniature in fig.1.30  . The Shroud is presented here as a long linen cloth on which the artist specially highlighted Christ’s holy face. The emperor kisses it. Giovanni Novelli notes: ‘Contrary to the legend about Akbar, the King of Edessa, in which ‘Mandylion’ (i.e. the Shroud – Author) is the size of a small napkin, the image from the manuscript depicts it in full length making it look like the Shroud’ [47], p.9. In fact there is no contradiction here. We have already explained that the four meter Shroud was most likely kept folded so, that on the outside, only on the surface the holy face of Christ was visible. That is why many authors mistakenly thought that the Shroud resembled a ‘small napkin’.

. The Shroud is presented here as a long linen cloth on which the artist specially highlighted Christ’s holy face. The emperor kisses it. Giovanni Novelli notes: ‘Contrary to the legend about Akbar, the King of Edessa, in which ‘Mandylion’ (i.e. the Shroud – Author) is the size of a small napkin, the image from the manuscript depicts it in full length making it look like the Shroud’ [47], p.9. In fact there is no contradiction here. We have already explained that the four meter Shroud was most likely kept folded so, that on the outside, only on the surface the holy face of Christ was visible. That is why many authors mistakenly thought that the Shroud resembled a ‘small napkin’.

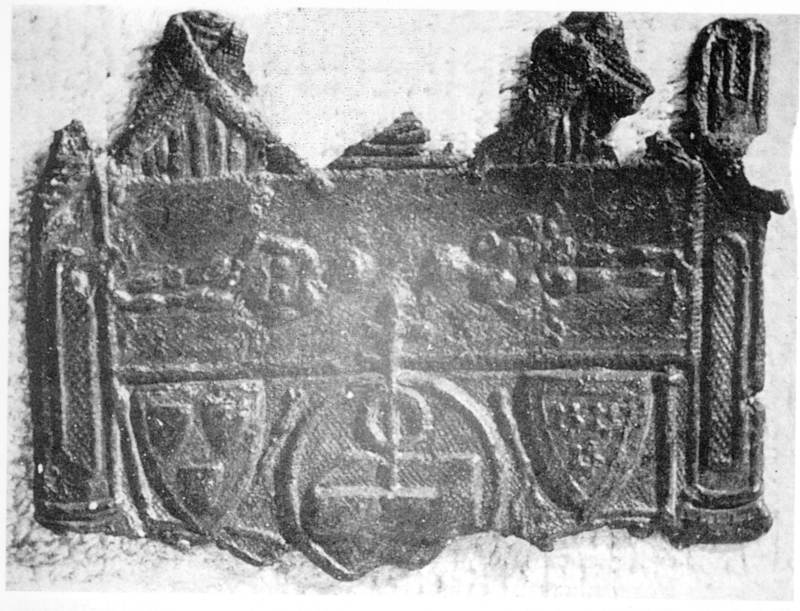

Fig.1.31 shows a lead medallion which they believe to be found in Seine river in France in the XIX century. In its upper part we can see the image of the Shroud and a double body image of Christ on it. It is believed that ‘this medal represents the coat of arms of Geoffroi de Charny, who the Shroud belonged to’ [47], p.31.

shows a lead medallion which they believe to be found in Seine river in France in the XIX century. In its upper part we can see the image of the Shroud and a double body image of Christ on it. It is believed that ‘this medal represents the coat of arms of Geoffroi de Charny, who the Shroud belonged to’ [47], p.31.

Giovanni Novelli wrote: ‘An extraordinary and controversial exhibition among other things concerning the Shroud opened in the British Museum from the 9th March to the 2nd September 1990 under the name of ‘Fakes? The Art of deception. Among the 350 presented exhibits, which turned out to be forgeries of the archaeological findings… the central ‘scientific’ part stood out. There at the place of honour was placed the largest object of the exhibition – the life size projection slide of the Shroud of Turin in a horizontal position on the table lit from underneath 4,5 x 1,2 m in size. The inscription represented the period when the Shroud appeared - 1260-1390 A.D., without any other comments!’ [47], p.44.

Further Giovanni Novelli reports: ‘1997, 12 April. The fire (causing suspicion) destroyed Guarini Chapel which has just been restored. The Shroud was saved and placed by the Official Custodian (of the Shroud), cardinal Saldarini into a secure vault’ [47], p.48. Thus we cannot rule out a possibility) that today someone is trying to destroy the precious original.

3.5. THE DIMENSIONS OF THE SHROUD AND THE HEIGHT OF CHRIST.

The Shroud is a gold and yellow handmade linen cloth. It is 4,43m long and 110cm wide [168]; [47], p.3. The height of the human body imprinted on the Shroud is approximately 178cm [47], p.4. It is not difficult to calculate it having measured the imprint on the Shroud.

We would like to note, that the 178cm height even today is considered quite tall. And this is in the age of ‘acceleration’, when a person’s height significantly increased. As early as in the beginning of the XIX century men were on average much shorter – approximately 150-160 cm. In particular the Encyclopaedia [90], v.7, column 429, published in the late 20s – early 30s, says that the average male height reaches 165cm. It means that 165cm is the maximum average height among various nations. Today this figure is considerably higher. Besides, if you look at the Mediaeval suits of armour it becomes apparent that the typical male height during that time was around 150 cm. The scientists found out long ago that human height increases over the centuries. That is why Christ’s height of 178cm must have been perceived by his contemporaries as very tall. In fact, as we will find out further, the records of Christ’s huge height survived in the original sources. Though the Gospels say nothing of it.

Today some people try to use the unusualness of the height for an ancient person on the Shroud as proof of it’s being a fake. Such a thought was presented, for example, in a BBC TV documentary, which was broadcast on Russian television in December 2003, not long before Christmas. However, as we will see below, the great height of the person on the Shroud is, on the contrary an argument in favour of its authenticity.

3.6. THE DAMAGED EYE OF CHRIST ON THE SHROUD.

The Image on the Shroud shows that the right eye of Christ was seriously damaged. We quote: ’There are signs of beating and swellings, one of which almost entirely deformed the right eye’ [47], p.16. When looking at the photograph what strikes us is that the right eye as if cut by a deep vertical wound, see. fig.1.17  . Moreover, various researchers pointed out ‘a torn RIGHT EYELID and a large swelling bellow the RIGHT eye… on closer examination we can see a long blood bruise on the RIGHT cheek’. See an article ‘Holy image on the cloth’ on the site at www.shroud.orthodoxy.ru, specially dedicated to the Shroud of Turin.

. Moreover, various researchers pointed out ‘a torn RIGHT EYELID and a large swelling bellow the RIGHT eye… on closer examination we can see a long blood bruise on the RIGHT cheek’. See an article ‘Holy image on the cloth’ on the site at www.shroud.orthodoxy.ru, specially dedicated to the Shroud of Turin.

The Gospels say nothing about it. However we will see yet again the direct proof that one of Christ’s eyes was in fact damaged (put out) immediately before the crucifixion. See below.