Addendum 1.

What happened to the treasury of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire after the great divide of the XVII century.

It is obvious that the Czars, or Khans, had an imperial treasury, and strove to expand it in every which way. The treasury contained gold, silver, gemstones, rare works of art etc. After the divide of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire, during the Great Strife and the Reformation mutiny of the XVII century, the treasury is most likely to have fallen prey to pillagers. Today we are unlikely to reconstruct all the details concerning the destiny of the treasury that belonged to the Khans of the Great Horde, or Russia; however, many related facts reveal themselves to a careful researcher. Let us, for instance, consider the background of the famous “historical” diamonds kept in the treasuries and museums of different countries. The reference literature we shall use is as follows: Encyclopaedia Britannica ([1118:1]), “Tales about Gems” by Academician A. E. Fersman (Moscow, Nauka, 1974, marked [876:1]) and “Gemstones” by N. I. Kornilov and Y. P. Solodova (Moscow, Nedra, 1983, marked [430:1]).

We shall be referring to the following large diamonds.

1) “The Diamond Tablet – an amazing individual stone [found in India – Auth.] . . . It is truly one of the so-called portrait stones . . . The stone is amazingly beautiful and pure and masterfully wrought in the old Indian cutting fashion, with two indentations covered in soft gold. This stone is but a shard . . . of some unknown gigantic diamond crystal found among the sands of Golkonda in India . . . Unfortunately, the fate of this diamond is unknown” ([876:1], page 218). It is presumed to have weighed around 242 karats (let us remind the reader that one karat equals 0.2 grammes). A small shard of the diamond, namely, the abovementioned diamond tablet (which weighs about 25 karats) is kept in the Diamond Vault of the Muscovite Kremlin. Incidentally, this fragment is nevertheless the largest “portrait stone” in the world ([876:1], page 219).

2) The “Orlov” diamond, circa 200 karats. Found in India. Named after Count G. G. Orlov. Kept in the Diamond Vault of the Muscovite Kremlin. “It has preserved the ancient Indian cutting shape from the very time of the Great Moguls in India. There are many legends and fairy tales that concern this famous stone” ([876:1], page 219). It is curious that initially the “Orlov” diamond “bore the name of ‘Great Mogul’” ([876:1], page 219).

3) The Diamond of the Great Moguls, initially weighing around 787 karats. Found in India. Its modern whereabouts are unknown ([1118:1]). In general, there is a fair amount of confusion in the application of the name “Great Mogul” to diamonds, which we shall soon witness. Nowadays the name is occasionally applied to different stones than in the epoch of the XVII-XVIII century.

4) Koh-i-noor (or Kuh-e Nur) diamond, around 191 karats. Found in India. “The famous Kuh-e Nur . . . was taken from the King of Lahor by the English troops during the conquest of Punjab; it belonged to King Karna already 3 thousand years before the new era” ([876:1], page 192). Ever since 1849 it has been kept in England; it was put in the royal crown of England in 1937 ([1118:1]).

5) “Shah” diamond, around 89 karats. Found in India. Kept in the Diamond Vault of the Muscovite Kremlin ([1118:1]).

6) “The imperial crown [of the Romanovs – Auth.] contains a stone whose purity and type resemble ‘Orlov’ to a great extent. It is a large diamond . . . of almost 47 karats. An amazing stone of Old India . . . It is exceptionally similar to the ‘Orlov’” ([876:1], page 220).

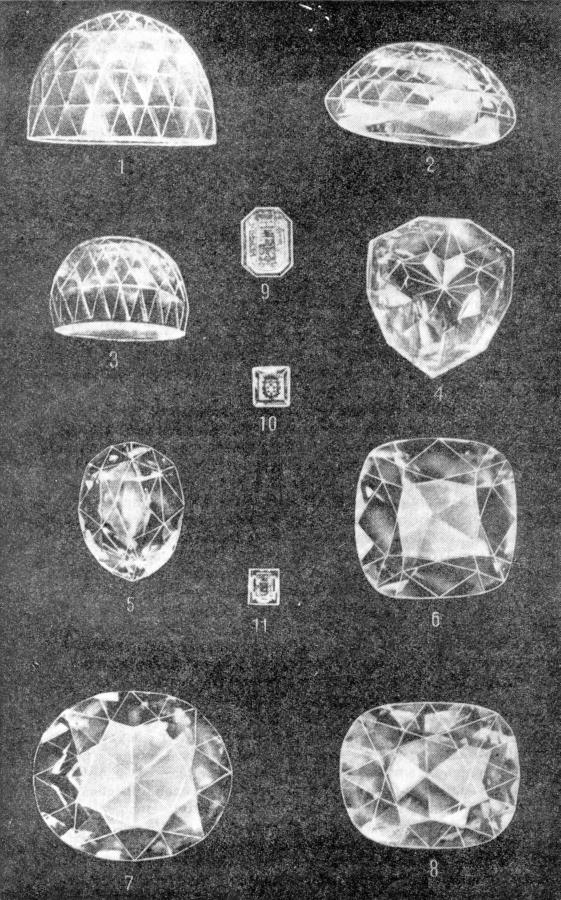

In fig. d1.1 one sees some of the world’s most famous diamonds ([876:1], page 197).

The history of the diamonds listed above is considered nebulous and full of contradictions nowadays. We shall shortly see why.

The “Orlov” diamond was discovered in India. This is what the Encyclopaedia Britannica tells us: “According to the legend, the diamond initially represented the eye of an idol that stood in a temple of the Brahmans in Misor. It was purloined by a French deserter who ran away to Madras. Others claim that the veracious history of the “Orlov” diamond can only be traced as far back as the middle of the XVIII century, which is when the stone was owned by Nader Shah, King of Persia (the assumption is that the diamond in question was the very diamond of the Great Moguls, presumed lost for a long time).

After the murder of Nader Shah, the stone was stolen and sold to Shaffrass, an Armenian millionaire. At any rate, the diamond was bought by Count Grigoriy Grigoryevich Orlov in 1774, who gave it to Empress Catherine the Great in a futile attempt to regain her favour. The Empress put the stone on the Sceptre of the Romanovs; nowadays it is kept in the Muscovite Diamond Vault” ([1118:1]). It is presumed that the stone’s “original weight must have equalled some 300 karats; the diamond in question was one of the two natural fragments of the large stone of the Great Moguls” ([876:1], page 219). It is also reported to be “the largest known diamond from India” ([876:1], page 220). On the other hand, A. E. Fersman claims that Count Orlov bought the “Orlov” diamond in 1772 ([876:1], page 220), and not in 1774, as the Encyclopaedia Britannica claims. There is obviously some confusion here.

“The diamond of the Great Moguls is the largest ever found in India. It was found as an uncut stone weighing 787 karats in the mines of Golkonda in 1650” ([1118:1]). In 1665 it was sighted by Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, a French gemstone dealer. “The present whereabouts of this stone are unknown; some are convinced that either ‘Orlov’ or ‘Koh-i-Noor” were cut from this stone after its loss, which followed the murder of Nader Shah, its owner, in 1747” ([1118:1]).

The “Shah” is a diamond that weighs around 89 karats, “with three inscriptions in the ancient Persian language engraved upon it, which indicate that it was discovered in 1591 - most likely, in the mines of Golkonda in India” (see fig. d1.2). The inscriptions refer to Nezam Shah Borhan II, 1591; Jahan Shah, son of Jahangir Shah, 1641, and Fath Ali Shah, 1829” ([1118:1]). Let us note that A. E. Fersman suggests a somewhat different interpretation of the third inscription found on the diamond in question: “1591 is the first engraved date; the stone was owned by Borhan Nezam Shah II in Ahmad Nagar; . . . 1641 is th

As we see, the Orlov diamond (qv in fig. d1.3) came into the scope of Romanovian history in 1774 or 1772, which is when it became the property Count Orlov. Let us now recollect that the “Pougachev War” was fought in 1773-1775. That is to say, the last “Mongolian” state was conquered by the Romanovs (in Siberia) and the USA (in America) as late as in 1775, as per our reconstruction. Therefore, the Romanovian nobleman G. G. Orlov came into the possession of the diamond right in the epoch of the last war fought against the Horde. It is likely that during the Great Strife of the XVII century a part of the Russian = “Mongolian” treasury was taken to the East by the Khans – to Siberia, or Muscovite Tartary, in other words, away from the Romanovs. However, about a century later the Romanovs invaded Siberia and the pillaging began. It is likely that other large “Mongolian” diamonds also ended up as part of the loot – the diamond of the Great Moguls, the “Orlov” diamond and others.

It has to be pointed out that all the famous diamonds mentioned above were associated with “India” in one way or another, or the Horde (Russia) of the XIV-XVI century, as we are beginning to realise. Russia was also formerly known as India, qv in CHRON5, Chapter 8:6.6. It was the name used by foreigners for referring to Russia. As we learn from the historians themselves, all such “Indian gems” fell into the hands of the Romanovs and the Reformist rulers of the Western Europe in the XVII century, which is the very epoch of the Strife and the fragmentation of the Horde. Romanovian history doesn’t even make any secret of the fact that the treasures in question were captured in the wars fought on the territory of “India” and “Persia” in the “orient”. Everything is correct – the Romanovs, the West European rulers and the USA were dividing the legacy of Russia, or the Horde, between them, including one of the richest treasuries in the world.

The gigantic diamond of the Great Moguls (or Great Mongols), weighing 787 karats, no less, must have been cut into several fragments so that it could be shared between several victors and then claimed “lost”. The fact that all these diamonds had recently belonged to the Russian Czars, or Khans of the Horde, was obviously concealed. As a result, the pre-XVII century history of these diamonds in its Romanovian version became convoluted and mysterious.

It becomes clear why the largest collection of gemstones in the world, or the Diamond Vault of the Muscovite Kremlin, was established by the Romanovs in the XVIII century ([876:1], pages 203-204). The first steps in this direction were taken by Peter the Great. Later on, “a large wealth of gems was accumulated under Catherine the Great. The court was served by a whole group of master jewellers, starting with the famous Jerome Posier and Louis-David Duval, who created many historical works of art and immortalised their names on the gems of the Diamond Vault” ([876:1], page 204). This must have been the time when the Romanovian jewellers was busy transforming the treasures purloined from the Horde in accordance with the new specifications, removing the “Mongolian” symbols, changing the frames of the gemstones and so on.

A large amount of valuable items formerly belonging to the Horde was captured by the Romanovs in the XVIII century on the territory of Muscovite Tartary – in the Ural region and in Siberia. This makes it clear why this is the very epoch when Catherine the Great (1729-1796) finally got the opportunity to “lay her hands on the Russian gemstones”, as A. E. Fersman is telling us ([876:1], page 204). “Special expeditions of gem-hunters were sent to the Ural region and to Siberia; millions of roubles were spent on the adornment of palaces with Russian marble and jacinth . . .” ([876:1], page 204). The Romanovs were ecstatically spending away the enormous legacy of the Horde, and putting the gems of the legitimate royal dynasty up for display as if they were theirs by right.

The expeditions that Catherine sent to Siberia and the Ural didn’t merely occupy themselves with the exploration of gem mines that became accessible, but also with the collection of all valuables they could find on the territory of the Muscovite Tartary. It also becomes clear why the famous Hermitage in St. Petersburg was founded under Catherine, in the year of 1765 ([876:1], page 223). This new capital of Russia, which was designed to replace “Moscow, the vicious Horde city” became the storage location for the treasures captured in the newly conquered Russian lands (the modern building of the Hermitage was built in the early XIX century, qv in [876:1], page 223).

Apparently, the rapid hoarding of treasures in the Hermitage began immediately after the “Pougachev war” – as we realise today, the treasures in question belonged to the Horde. Furthermore, it turns out that “the vogue for gems and diamonds in particular us described in a number of memoirs and notes dating from Catherine’s epoch; the vaults of the Hermitage were being filled at the highest rate between 1775 [right after the defeat of ‘Pougachev’ in 1774, that is – Auth.] and 1795” ([876:1], page 226).

The amount of treasures captured from the Horde must have been truly enormous – only to think it took twenty years to hoard them together at the Hermitage. Obviously, the valuable objects didn’t come from the Muscovite Tartary alone – this is, for example, what Catherine wrote to Grimm in this respect: “The silverware is in the shed they call a museum, likewise its kin of gold, silver and precious stones hailing from every corner of the world [and apparently collected by the Khans of the Horde – Auth.], likewise jacinth and agate galore, brought from Siberia; the mice and yours truly come there to admire all this splendour” (quotation given in accordance with [876:1], page 226).

The Empress was very proud indeed, and must have enjoyed her walks through empty halls filled with spoils of war. There was so much piled up that the countless Horde’s diamonds were used virtually everywhere: “Diamond jewellery became very fashionable – diamonds adorned earrings, buckles for shoes and belts, cufflinks, buttons, bracelets, ribbons, bunches of flowers, snuffboxes and combs . . . This is the very time [the second half of the XVIII century, that is – Auth.] when the best master jewellers lived on the Millionnaya Street of St. Petersburg, many of which took orders from the royal court” ([430:1], page 16). “Diamonds became especially popular in Russia under Catherine the Great. They adorned key-rings, buckles, snuffboxes, walking-sticks, shoes, garments etc” ([430:1], pages 76-77).

The above also explains the events of the epochs that followed, which are rather odd as regarded from the viewpoint of the Romanovian historians. It turns out that this splendorous but rather brief spell of rapid wealth accumulation under Catherine the Great was followed by a truly enigmatic decline. According to A. E. Fersman, “after Catherine the Great, the old traditions started to fall into oblivion. The former magnificence and splendour of Catherine’s court obviously weren’t abandoned at once, and the use of gold, silver and precious stones continued – however, a period of decline followed soon enough. Patronage for master jewellers was replaced by petty commercial schemes. Jewellery was no longer an art that enjoyed the support of the state. Less and less gems were bought . . . The apogee of this decline of style and art was reached under Alexander II. Throughout the entire XIX century, we see nothing but constant deterioration afflicting jewellery as an art as well as the Diamond Vault . . . The latter did not grow at all - on the contrary, the depletion of the vaults carried on endlessly . . .” ([876:1], page 204).

Everything is perfectly clear. Having thoughtlessly squandered the enormous wealth of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire, and being rather inept in the exploration of the precious stone mines in Siberia and the Ural region, the Romanovs became impoverished – after all, many professional secrets of the Horde’s craftsmen may also have become lost after the fall of Muscovite Tartary. We are being evasively told about “constant deterioration afflicting jewellery as an art”. Everything is perfectly clear – there was nothing left to rob (as compared to the epoch of the reckless robbery and the share-out of the “Mongolian” Empire’s treasury). New jewellery made by the Romanovian jewellers already after the epoch of Catherine was a lot less masterful than that made by the jewellers of the Horde. According to A. E. Fersman, “the coarse and heavy items dating from the epoch of Alexander II as compared to the fine jewellery of the middle of the XVIII century attain historical, artistic and material worth in our days as a relic of decadence . . .” ([876:1], page 295).

“Under the last Romanovs beautiful old items of the XVIII century perish recycled . . . Old jewellery is destroyed, gems are taken out of their frames . . . Much of the old jewellery was undone by merciless hands and transformed into the embodiment of heavy Teutonic kitsch and decline of style as well as artistic intuition” ([876:1], page 204).

Moreover, the jewellery of the Horde started to flow towards the Western Europe and America en masse: the Romanovs sold a great deal, which is also easy enough to understand, seeing as how the “Mongolian” jewellery was valued especially high in the West, which must have kept the memory of the Horde’s riches alive - the treasure that the Westerners once craved. Apparently, the Western Reformist victors of the XVII-XIX century must have considered it a particular honour to adorn their collection with a “Mongolian” item of some kind as a symbol of victory over the “Russian bear”, once feared and respected.

The result is as follows: failing to comprehend the historical picture in its entirety, A. E. Fersman is surprised to write the following: <<There is another facet to the history of the Diamond Vault that has to be pointed out – an almost complete absence of Russian gems in its vaults. Where are the purple amethysts glowing crimson red in the evening, brought from the Ural by the expeditions Catherine sent for this specific purpose? Where is the sublime schorl, lifeless under artificial light – the stone that the academies raved about in the late XVIII century, worn as a symbol of love for one’s motherland? Finally, where are the Russian emeralds? Where is alexandrite, everybody’s favourite?

The archives reveal the real reason behind this: a most dismal lack of taste that led to the inability of valuing Russian gems . . . These historical stones “perished” – some were cut into pieces, others sold at auctions. In the year of 1906 alone more than 1 million golden roubles’ worth of gems from the Chamber Section was sold, including unique items – beautiful Russian emeralds, ancient amethysts of Catherine the Great and many other valuables whose historical, scientific and material worth was either unknown to, or ignored by, ‘His Majesty’s Cabinet of Ministers’. This is how we see the destiny of the Diamond Vault – it reflects the course of Russian history itself>> ([876:1], page 205).

Let us conclude with a very typical detail. Modern geologists interested in history point out a strange fact, formulated with precision by A. E. Fersman: “The Russian diamond industry only dates as far back as to the first half of the XIX century, and one finds it hard to believe the authors from the days of yore claiming that Russian, or Scythian, diamonds were known to the ancient Greeks” ([876:1], page 198). It turns out that the “ancient” authors claimed there were diamonds in Russia, or Scythia, whereas the modern geologists, all too ready to trust the Scaligerite and Romanovian historians, are convinced that the Russians didn’t have any diamond industry before the XIX century.

Which party is correct? As we realise today, the “ancient” authors described everything accurately and wrote their works in the epoch of the XV-XVII century. Moreover, Russia, or the Horde, was known as “India” in the West (the word derives from the Russian word “inde”, which translates as “far away”. Historians are unanimous about the legendary mediaeval India being exceptionally rich in gold and diamonds. Historians and geologists report the following: “The largest and most famous stones, such as Koh-i-Noor, Regent, Orlov, Derianoor, Sanci, Shah, Hope, Florentine, Dresden Green etc come from the Indian mines” ([430:1], page 73).

The mythical “ancient India” was virtually drowning in gems. “Emeralds adorned the luxurious attires of the Great Moguls [Great Mongols, in other words – rulers of the Empire or their vicegerents – Auth.], who blinded the enslaved nations by the brilliance of shining gems” ([876:1], page 208). Furthermore, it is reported that in the alleged XIII century (the epoch of the XV-XVI century in reality) “European markets were drowned in Indian diamonds; jewellers found it problematic to cut this beautiful stone” ([876:1], page 189).

We must emphasise that in the epoch of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire valuable objects produced in different parts of the Empire (in Asia, Europe, America and so on) were considered imperial property belonging to the court of the Khans that ruled the entire Empire. Regional segregation was to come much later, in the XVII century, which is when the Empire fell apart and tension started to grow between its former fragments, leading to armed confrontation.

As we have already explained, in the XVII century historians took the name “India” away from Russia, or the Horde, and made it correspond to a tiny part of the former Great = “Mongolian” Empire, namely, modern India. As a result, mediaeval Russia automatically became “void of diamonds” and “rather poor”, whereas the mediaeval Hindustan Peninsula transformed into a mysterious land of unbelievable luxury. The true state of events was turned upside down. Our reconstruction aims at restoring the correct picture of the past.

It is curious that the “ancient” and mediaeval sources keep on telling the story about the strange method of diamond mining in the “mysterious India”. However, a closer look at the original sources reveals that they were referring to Scythia initially – which is perfectly correct, since in the Middle Ages the name “India” stood for Russia, or the Horde, also known as Scythia (which also used to comprise the territory of the modern India, by the way).

G. Vermoush tells us the following: <<One of its [the legend’s – Auth.] initial versions was related in sufficient detail in the IV century [the XIV century the earliest, most probably – Auth.] in a work of Epiphanios, Bishop of Cyprus, dedicated to the twelve holy gems (the ones that adorned the ring of Aaron) . . . This is what he writes: ‘There is a valley here, in the deserts of Great Scythia, deep as any abyss . . .’>> (page 47).

Further it is written that the gemstones can be found at the bottom of the valley, where people throw pieces of fresh animal carcasses, still warm, which the stones stick to. The eagles that fly above the abyss descend and grab the meat, then fly back upwards and devour eat. After that, people come to the feeding place of the birds and collect the diamonds that remained here. This strange story probably describes some real technology of diamond mining that was misunderstood by the mediaeval European travellers and became a bizarre legend. For the time being, we aren’t concerned with the nature of this technology, but rather the fact that the diamonds came from Great Scythia, also known as India. As G. Vermoush tells us further, the second group of legends concerned with diamond mining locates the same events in China (page 47-48). As we realise today, this is correct as well, since Scythia was also known as China (“Kitai”).

Let us point out the following linguistic element.

In "ancient India" the weight of precious stones, in particular diamonds, was measured in units, called "rati" (p.92 of G.Vermush's book). Later, in the XVII-XVIII centuries, this name was transformed into a word known today "carat", and the exact equivalent, connecting "rati" and "carat" was, as it is considered, lost (!?). Since "ancient India" is Rus-Horde of the XIV-XVI centuries, it is possible that the name "rati" reflected Russian word SERIES, ORDA, ORDER, that is, as if an indication of the metropolis The Horde Empire, from where the jewelery was mainly supplied to all ends of the world. And the word "carat, "is, perhaps, only a slight distortion of the Western European word HORDE, that is, the same words ORDA. Nevertheless, today's historians assure us that the Latin word KARAT denoted the seed of the baobab exclusively. (p.92 of the book by G. Vermush). It is understandable now why another old unit of measurement weight of precious stones in "India" was MANGELIN (p.92 of the book G.Vermusha). That is, naturally, the MONGOLIAN unit of weight.