Part 1.

Russia as the centre of the “Mongolian” Empire and its role in mediaeval civilization.

Chapter 1.

“Peculiar” geographical names on the maps of the XVIII century.

7. On some maps of the XVIII century Russia and Moscovia are written as names that refer to different region.

We shall refer to the unique antique editions of the XVIII century – the geographical atlases of the world [1018] and [1019]. The first of them was dedicated to “The Prince of Orange”, and its compilation took the effort of a whole team of cartographers in London, Berlin and Amsterdam.

Let us, for instance, turn to the map of Europe dating from 1755 and entitled “4-e Carte de l’Europe divisée en ses Principaux États. 1755” with comments in French, qv in fig. 1.17. What we see in fig. 1.18 appears to be a preliminary version of the same map compiled a year earlier, in 1754.

The detailed map that dates from 1755 (fig. 1.17) depicts Russia (Russie) in the area of the modern Ukraine, whereas the large area to the North and the East is called Moscovia (Moscovie). The city of Moscow is located on the border of Russia and Moscovia – halfway in between. The area adjacent to Moscow is called “Gouvernment de Moscou”, qv in fig. 1.19.

Fig. 1.18. This is what appears to be the preliminary version of the map of Europe created in 1754. Taken from the Atlas of 1755 ([1018]).

Fig. 1.19. Muscovia and Russia are depicted as two different countries. Fragment of a map dating from 1754. Taken from [1018].

Fig. 1.20. The territory referred to as “Kiev Government” is depicted as part of Russia. Map fragment dating from 1754. Taken from [1018].

Fig. 1.21. A part of the modern Prussia is referred to as “Russie”, or Russia. Map fragment dating from 1754. Taken from [1018].

However, this is in good correspondence with our reconstruction, according to which the new dynasty of the Romanovs had only managed to seize a relatively small area adjacent to Moscow, known as Moscovia, after the fragmentation of the gigantic mediaeval Russia (Horde) in the XVII century. Other regions had either still remained independent from the Romanovs, or tried to forget their former ties with Russia.

We see an area around Kiev, within Russia, marked as “Gouvt. de Kiowie”, or “Kiev Government”, qv in figs. 1.19 and 1.20. Therefore, the Kiev region was still known as Russia in the XVIII century. The Ukrainian scientists are therefore correct to refer to the Kiev state as to Russia. However, we all know the old name “Kiev Russia”. So, even in the XVIII century certain geographical maps compiled in the West preserved some information about Russia, or the Horde, of the XIV-XVI century.

As a matter of fact, the very same map refers to the South of the modern Ukraine as “Lesser Tartary” (Petite Tartarie), qv in fig. 1.20. It is significant that inside the “Lesser Tartary” we see the legend “Zaporozhye Cossacks” (Cosaques Zaporiski). In other words, the Cossacks of Zaporozhye lived on the territory of the Lesser Tartary. This is also in perfect concurrence with our reconstruction, according to which the Tartar Horde can be identified as the Cossack Horde. Thus, the fact that the Tartars and the Cossacks were really the same is directly mentioned on the maps of the XVIII century. Later on it was forgotten.

To the west of Lithuania and to the north of Poland, on the coast of the Baltic Sea, the area around Königsberg and Danzig (Dantzick) is marked “Russe”, or “Russia” (figs. 1.19 and 1.21). Modern readers might suggest that the country in question is really Prussia; however, we don’t see the Roman letter P anywhere. The Prussians were still occasionally referred to as Russians in the XVIII century, in other words.

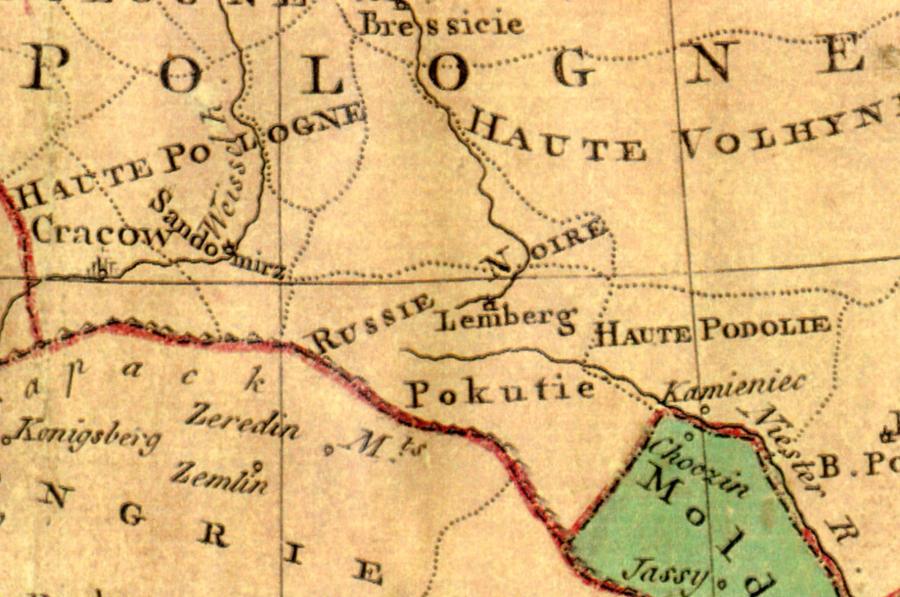

Fig. 1.22.

We see the area of “Russie Noire” (“Black Russia”) next to Lemberg (Lvov).

Map fragment, 1754. Taken from [1018].

In general, one has to point out that the Russians are also referred to as “Russie Noire” – see the region in the south of Poland, right next to Lvov (Lemberg), qv in fig. 1.22. The name “Russia” is thus encountered in a least three different parts of a map of Europe dating from the XVIII century.

Let us turn to another French map of 1754, known as “III-e Carte de l’Europe. 754”, qv in [1018], [1019] and fig. 1.18.

Once again we see three different regions adjacent to each other – Russia, Moscovia and Lesser Tartary. Lesser Tartary is the South of the modern Ukraine, Russia identifies as the rest of the Ukraine, and Moscovia starts from Moscow and reaches the Zapadnaya Dvina in the West, the Arctic Ocean in the North, and the 75th meridian in the East – well beyond the Ural, spanning more than half of Siberia (see fig. 1.18).

8. The name of the Russian Empire in the maps of the XVIII century.

According to Millerian and Romanovian history, the “yoke of the Mongols and the Tartars” ended in 1480, under Ioann III Vassilyevich. One must expect that after liberating themselves from the rule of the hated foreigners who are said to have oppressed Russia for some 240 years, Russians would sigh with relief and do their best to forget the centuries of slavery and terror. At any rate – one would expect them to revive the old, or Russian, names of cities and regions and obliterate the ones coined by the “Tartars and the Mongols”.

The process would be perfectly natural – every enslaved nation, having got rid of a bloody and merciless yoke as a result of a liberating war, is only overjoyed to revive the original names on the map of its own country.

What do we see happen in Russia? If we decided to ask the readers about the name of the Russian Empire in the middle of the XVIII century – repeat, the eighteenth century, the readers, raised on the Romanovian version of Russian history, would instantly reply that it was called precisely that – the Russian Empire.

The answer is correct. Maps of the XVIII century really bear the legend “Russian Empire”. Now let us enquire about whether the Russian Empire could possess any other names in the XVIII century. One should ponder this well; modern textbooks on Russian history report nothing of the sort.

Let us turn to the map of 1754 entitled “II-e Carte de l’Asie”, qv in figs. 1.23 and 1.24, as well as the map reproduced in fig. 1.25. We shall see the gigantic inscription that says “Empire Russienne” that runs across the entire territory of the Russian Empire, up to the Pacific, including Mongolia and the Far East. However, the same enormous territory has a second legend ascribed to it – “Grande Tartarie”, or the Great Tartary; the letters are three times bigger. If we are to recollect that the word “Great” was occasionally read as Megalion, or Mongolia, we shall come up with “Mongol Tartary”. The map in fig. 1.25 is virtually the same, dating from 1754 and entitled “I-e Carte de l’Asie”.

Fig. 1.23. Map of 1754 entitled “II-e Carte de l’Asie” from the Atlas of 1755. Northern part of the map. The legend “Grande Tartarie” (Great Tartary) is set in huge letters that cover the entire territory of the Russian Empire. Taken from [1018].

Fig. 1.24. Map of 1754 entitled “II-e Carte de l’Asie”. Southern part of the map. Taken from [1018].

Thus, as recently as in the XVIII century, the Russian Empire was also known as “Mongol Tartary”. The fact that the two names refer to the same territory is explicitly written on maps of the XVIII century.

Can this really be true? Romanovian history assures us that the “terrible yoke of the Tartars and the Mongols” was lifted some 300 years before the compilation of this map at least. Could it really be that three centuries did not suffice in order to make foreigners forget the “Tartar and Mongol” name of Russia?

There is nothing mysterious about this fact. The “Mongol” empire of the Tartars, also known as the Great Russian Empire in the pre-Romanovian epoch, had existed for several centuries before the Romanovs enslaved Russia in the early XVII century. After the deposition of the old dynasty, which we shall be referring to as the Horde Dynasty, the process of re-writing Russian history in the pro-Romanovian vein commenced as a political necessity.

This editing process resulted in the creation of a political fairy tale about the “vicious” Mongols and Tartars, who had enslaved Russia in the days of yore. The old Russian word “Horde” (army) was demonised by Romanovian historians, eager to please. All of it happened gradually, step by step.

Nevertheless, the name of the famous Great Empire, or the “Mongolian” Empire of the Russians and the Tartars, was kept for centuries to come, since the entire world had known Russia under this very name for many centuries.

It took the Romanovs an enormous amount of time to create a layer of plaster over the authentic history of Russia. This must have been made relatively quickly in Russia. Yet the foreigners didn’t part with the habit of using the old name for referring to Russia for a long time. As we have just seen, they carried on writing the old name alongside the new (Great Tartary and Russian Empire).

The old name eventually went out of use, with nothing but the “Russian Empire” remaining in its place. This is how the last traces of the “Mongol and Tartar” dynasty of Horde Russia were obliterated. Russians would refer to it as the Cossack Dynasty of Great Russia, or the Great Cossack Dynasty. Bear in mind that “Mongol Tartary” was the name used by foreigners, and apparently hadn’t existed in the Russian language. The name “Mongolia” must be of the same origin as the Russian words “mnogo”, “moshch” and “mnozhestvo”, translating as “many”, “might” and “multitude”, respectively.

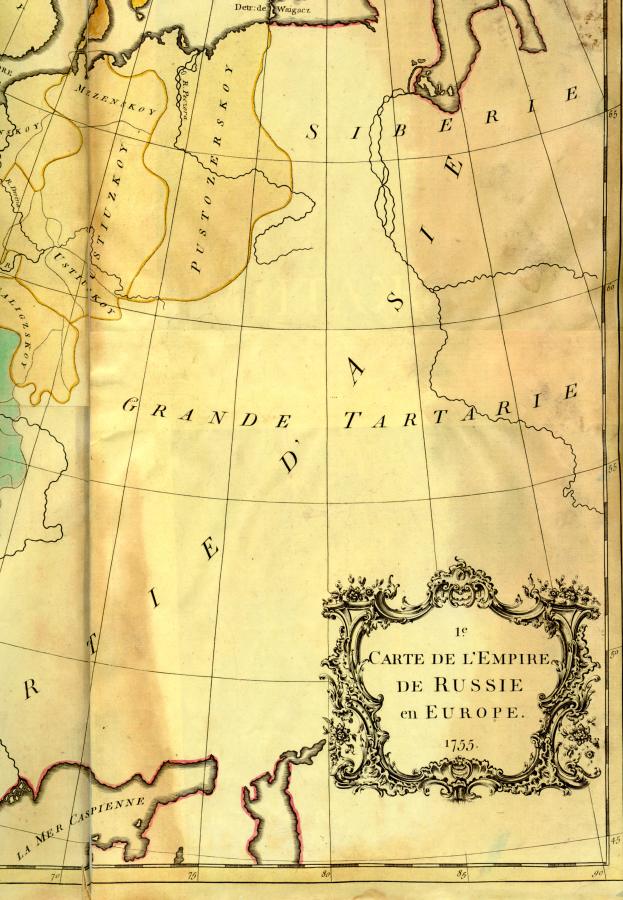

We see the same to be the case with a number of other maps dating from the XVIII century. For instance, there is the “First Map of the Russian Empire and Europe” (“I-e Carte de l’Empire de Russie et l’Europe. 1755.” See figs. 1.26 and 1.27. The legend “Grande Tartarie” is written all across the Russian Empire (translated as “Mongol Tartary”).

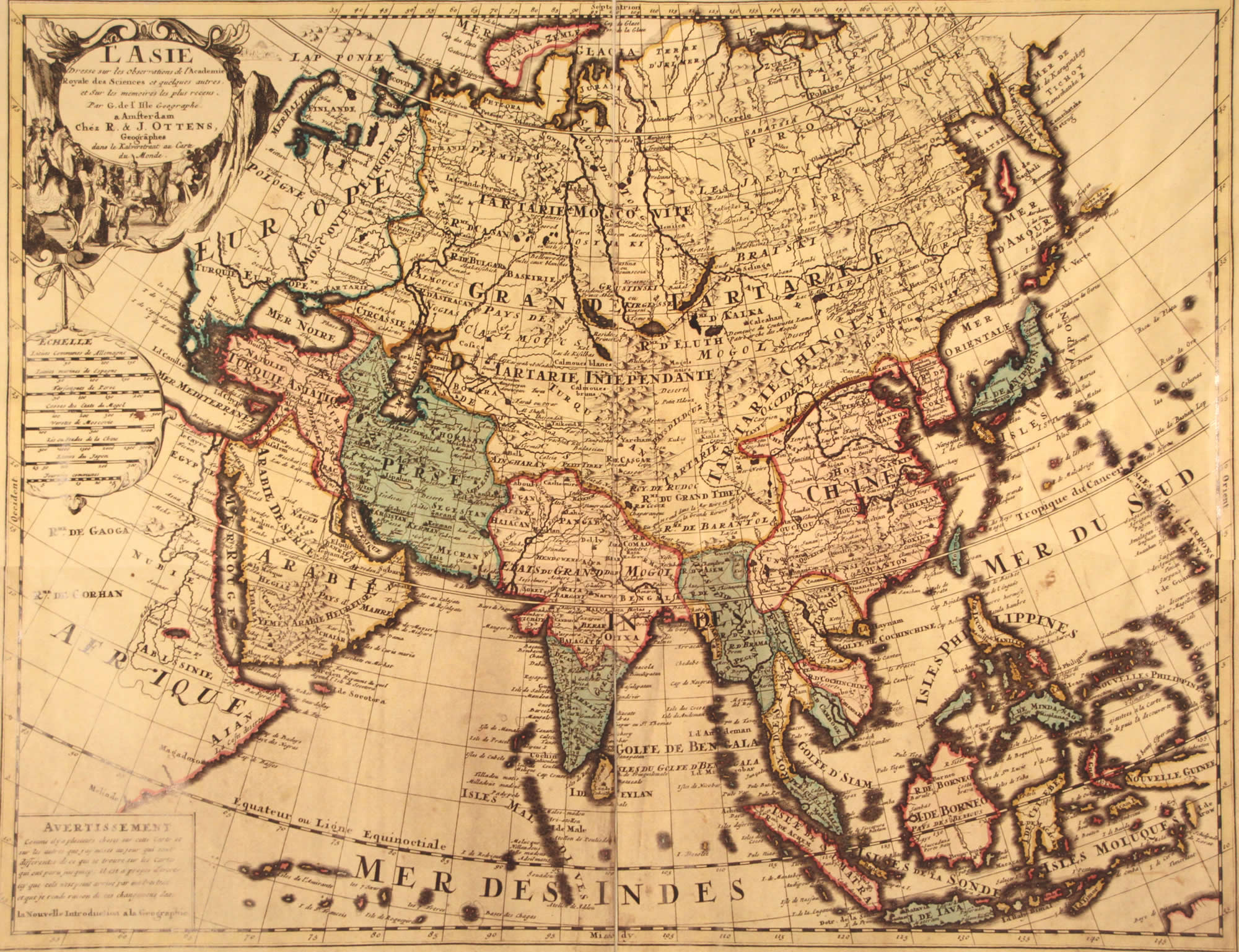

Next we have another map of the XVIII century under the following title: “L’Asie dressé sur les observations de l’Academie Royale des Sciences et quelques autres, et sur les memoires les plus recents. Amsterdam. Par G. de l’Isle. Geographie à Amsterdam. Chez R. & J. Ottens (see figs. 1.28 and 1.29). The exact date of its compilation is unfortunately missing.

Fig. 1.26. Map of Europe and the Russian Empire entitled “I-e Carte de l’Empire de Russie en Europe. 1755”. The words “Grande Tartarie” (Great Tartary) are stretched across the entire territory of the country. Taken from [1018].

Fig. 1.27. Eastern part of the map entitled “2-e Carte de l’Empire de Russie en Europe. 1755”. Russia is called “Grande Tartarie”, or “Mongol Tartary”, in other words. Taken from [1018].

Fig. 1.28. Map of Asia dating from the XVIII century. An enormous part of Eurasia that includes many other countries besides Russia is referred to as “Grande Tartarie”. Western part of the map. “L'Asie dressé sur les observations de l'Academie Royale des Sciences et quelques autres, et Sur les memoires les plus recens. Amsterdam. Par G. de l'Isle Geographie a Amsterdam. Chez R. & J. Ottens”. Taken from [1019].

Fig. 1.30. Central part of a map of Asia dating from the XVIII century. We see several Tartaries here. Taken from [1019].

To the West of the Volga we see “European Moscovia” (“Moscovie Europeane”). The entire territory of the Russian Empire to the East of the Volga is marked “Grande Tartarie” in large letters – Great (“Mongolian”) Tartary, in other words (see fig. 1.30). It is significant that we see “Muscovite Tartars” residing in Great Tartary. The area marked “Tartarie Muscovite” is quite large, much bigger than many countries of the Western Europe, and covers a significant part of Siberia, qv in fig. 1.30.

By the way, we see other “Tartar regions” on the territory of the Russian Empire, or Great Tartary – Independent Tartary (Tartarie Independante), Chinese Tartary (Tartarie Chinoise), a Tartary right next to Tibet and “Lesser Tartary” comprising the Crimea, the South and the East of the Ukraine.

Fig. 1.31. Fragment of a map of Asia dating from the XVIII century. We see India as part of the Kingdom of the Great Moguls. Taken from [1019].

To the West of the Volga we see “European Moscovia” (“Moscovie Europeane”). The entire territory of the Russian Empire to the East of the Volga is marked “Grande Tartarie” in large letters – Great (“Mongolian”) Tartary, in other words (see fig. 1.30). It is significant that we see “Muscovite Tartars” residing in Great Tartary. The area marked “Tartarie Muscovite” is quite large, much bigger than many countries of the Western Europe, and covers a significant part of Siberia, qv in fig. 1.30.

By the way, we see other “Tartar regions” on the territory of the Russian Empire, or Great Tartary – Independent Tartary (Tartarie Independante), Chinese Tartary (Tartarie Chinoise), a Tartary right next to Tibet and “Lesser Tartary” comprising the Crimea, the South and the East of the Ukraine.

The North of India is called “The State of the Great Moguls”, qv in fig. 1.31. The Moguls are the same as the “Mongols”, or the Great Ones. In CHRON4 we cited the evidence of certain mediaeval chroniclers, who mentioned that the Russian language “might have been used” in many parts of India. This must have been the gigantic region known as “États du Grand Mogol” comprising almost all of India, up to the 20th degree of northern latitude.

It is noteworthy that Great Tartary included Chinese Tartary, qv in fig. 1.29. It covered a part of the modern China as well as the “Great Tibet”. We shall relate the history of China, its real events and chronology in the chapters to follow, coming back to these remarkable maps of the XVIII century.

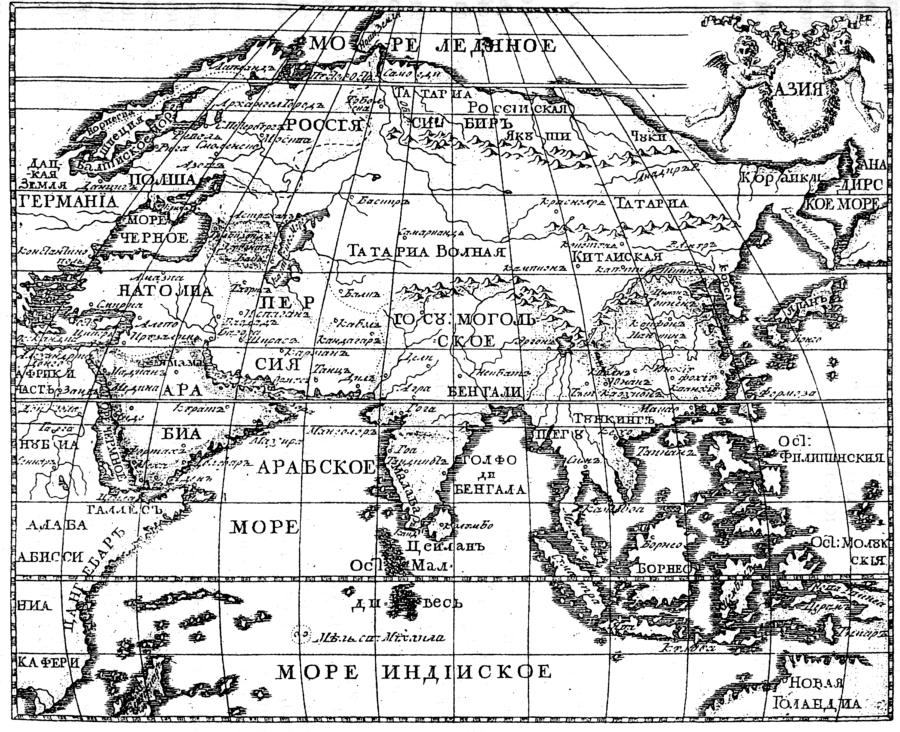

The “Tartar” geographical terminology had been used on Russian maps up until the XVIII century. For instance, in fig. 1.32 we see a map of Asia taken from the “first Russian atlas of world geography” originally known as “The Atlas Compiled for Prudent Use by the Youth, and All Readers of Chronicles and Historical Book” published by the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg in 1737 (map 18 of [679], page 48). We see numerous Tartaries on the map – Tartary, Independent Tartary and Russian Tartary, qv in fig. 1.32. A. V. Postnikov, the compiler of the atlas ([679]) couldn’t restrain himself from the following sceptical comment: “Apparently, the sources of the maps were foreign maps of low quality in different languages” ([679], page 48)

Fig. 1.32. Russian map of Asia dating from 1737 that still indicates several Tartaries. Taken from [679], page 48.

Fig. 1.32a. Fragment of the Russian map entitled “A View of the Earth Globe” dating from the middle of the XVIII century.

Apart from Great Tartary, we also see Free Tartary and Chinese Tartary. Taken from [306:1].

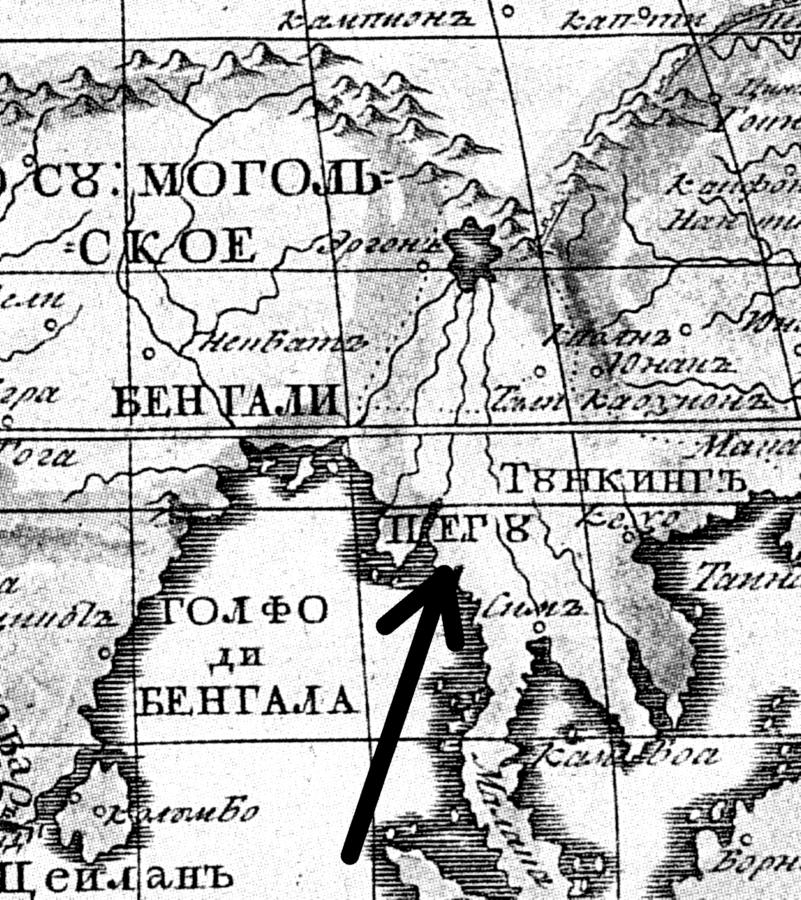

Fig. 1.33. Fragment of a map of Asia dating from 1737, which indicates an area called Pegu. The name is likely to be derived from “pegaya orda” (“Dapple Horde”). The name “Pakistan” could be of the same origin as well. Taken from [679], page 48.

Great Tartary is also marked on a Russian map dating from the middle of the XVIII century, a fragment of which is reproduced in fig. 1.32a.

Incidentally, a map of 1737 reproduced in fig. 1.32 refers to the area of Burma (Myanmar) as to “Pegu”, qv in fig. 1.33. Could this be a relic of the “Motley Horde”, or “Pegaya Orda”, described in Chapter 6 of CHRON5, whose name became reflected in those of Peking and Pakistan?

9. The former identity of Lithuania.

Let us turn to Y. Y. Shiryaev’s collection of geographical maps entitled Byelorussia: White Russia, Black Russia and Lithuania on Maps ([977]).

1) It turns out that up until the XIX century Lithuania was the name used for the territory known as Byelorussia today, whereas the modern Lithuania was known as Zhemaytia or Zhmud.

2) It turns out that the Lithuanian language had not been used as the official language of the Great Principality of Lithuania – the populace spoke Russian, or Old Byelorussian (a western dialect of the Old Russian language).

Let us quote what Y. Y. Shiryaev has to say on the subject: “The Great Principality of Lithuania was formed on the territory of Byelorussia in 1240. Its capital was the city of Novogrudok . . . The greater part of the modern Lithuania, or its western half, was known as Zhemaytia (Zhmud) or Samogitia (Latin name) and not as Lithuania. It had been an autonomous principality and part of the Great Principality of Lithuania, as one see from many of the ancient maps reproduced in the book. Its citizens were called Zhmudins.

The modern name [or Lithuania as used for referring to the modern state of Lithuania – Auth.] has only been used starting with the second half of the XIX century. The official language of the Great Principality of Lithuania had been Old Byelorussian – up until the end of the XVII century, and it was eventually replaced by Polish. One must note that Lithuanian had never been an official language in the entire history of the principality. The Great Principality of Lithuania wasn’t only considered Slavic in language and culture, but also due to the fact that the majority of the populace had been Slavic” ([977], page 5).

When did the change of historical names occur? Y. Y. Shiryaev gives an explicit answer to this question. “In the XIX century the course of events has led to a shift of historical conceptions and the names of ethnic groups and territories. Thus, the former ethnic territory of Zhemaytia became known as Lithuania, whereas the traditional toponym ‘Lithuania’, formerly identified with the North-Western Byelorussia (including the area around Vilna) has completely lost its ethnic and historical content” ([977], page 5).

It would be hard to formulate it more clearly. This is explained perfectly well by our conception, according to which Lithuania is the former name of White Russia, also known as Moscovia.

Fig. 1.34. Fragment of an ancient map allegedly dating from 1507. “Map of Central Europe by M. Beneventano and B. Vanovski (reworked by Nicholas of Cusa) from Ptolemy’s ‘Geography’, 1507” ([977], page 114). Taken from [977], Map 2, page 21.

This fact is confirmed by old maps. On a map dating from the alleged year 1507, which is reproduced in Y. Y. Shiryaev’s book, we see the explicit legend: Russia Alba sive Moscovia (“White Russia, alias Moscovia”), qv in fig. 1.34, right part of the map. However, V. Ostrovskiy, a modern commentator, translates this perfectly clear inscription as “Greek Orthodox faith, or Moscovia”, for some bizarre reason.

This outrageous translation can be seen in V. Ostrovskiy’s book ([1323]; quotation given by [977], page 9). Ah, the things one does to save Scaligerian and Romanovian history!

Further on, our reconstruction implies that the city of Novogrudok, or the capital of the Great Principality of Lithuania founded in 1240, is most likely to identify as the very Novgorod the Great, or Yaroslavl. After all, 1240 is the actual year when the “Mongolian” conquest began, according to Scaligerian and Romanovian history.

The name Samogitia as used in the old maps is of similar origins – “samo-gotia”, or “The Actual Land of the Goths”. Another explanation is possible – Samogitia = Land of the Goths, since the Polish word for “land” (ziemia) may have easily transformed into “samo”. We have already mentioned that the Goths and the Tartars are the same nation historically, qv in the book of Herberstein ([161]).