Part 1.

Russia as the centre of the “Mongolian” Empire and its role in mediaeval civilization.

Chapter 3.

Vestiges of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire in documents and on the artefacts found in Europe and Asia.

1. The allegedly illegible inscriptions on mediaeval swords.

Inscriptions presumed illegible are by no way an exclusive trait of Russian coins. One finds them on the numerous mediaeval swords found in Europe and particularly on the territory of the former USSR and its immediate neighbours ([254]).

A. N. Kirpichnikov, a famous specialist in the history of mediaeval weapons, reports the following: “In the 1870’s A. L. Lorange, a staff member of the Bergen Museum in Norway, began to study the swords of the Vikings, and was amazed to have found previously undiscovered symbols and lettering upon them . . . By 1957 K. Leppäaho had furbished 250 early mediaeval swords and found dozens of inscriptions and symbols . . . In 1963 A. K. Antejn, a historian and a specialist in metallic artefacts, started his research of swords . . . The scientist found over 80 blades with lettering, symbols and ornamentation in the museums of Latvia and Estonia . . . Over 99 swords found . . . on the territory of the ancient Russia, in Latvia and in the Kazan region of the Volga have been studied [by A. N. Kirpichnikov – Auth.] . . .

Formerly unknown shapes were found on 76 blades . . . The amazing abundance of letters and symbols that were revealed on the objects known quite well and for a long time, is explained by certain peculiarities of the branding process . . . the symbols and the lettering found on the objects of the IX-XIII century . . . were branded while still red hot with the use of iron or damask wire. Even after removing the layer of corrosion from the blade, these shapes are hardly visible at all. It was only after the application of a special etching solution known as the Hein reactive (copper and ammonium chloride) that the surprised observers could see the symbols that appeared on the blades as though they came from the very depths of oblivion” ([385], page 149).

It is presumed that the letters in questions transcribed “the names of the smiths who had forged the blades or their workshops. The craftsmen have been Carolingian and came from the Western Europe – they must have worked in the regions of the Rhine or the Danube . . . Some of the names were unknown previously or very rare. Therefore, the Russian soil has preserved the work of several Occidental smiths who remain forgotten in their homeland” ([385], page 50).

Let us ask the following question: how do we know that these swords were made in the Western Europe, if the names of the craftsmen inscribed on them are unknown in those parts? We shall cite a very vivid example from an article in [385], which illustrates the “method” used by the archaeologists in order to “identify” the origins of such swords. A. N. Kirpichnikov reproduced a photograph, adding the following comment: “this beautiful sword handle, shaped as intertwined monster bodies, allowed to identify the blade as Scandinavian” ([385], page 51).

Thus, the country of origin is identified by the beauty of the sword’s handle. Finely wrought handles must come from Scandinavia or Western Europe, plainer ones may end up classified as Russian.

However, A. N. Kirpichnikov has discovered the lettering that said “Lyudota Koval” on one of these “typically Scandinavian” swords ([385], page 54). The first word is a Slavonic name, and the second, a well-known Slavonic word for “smith”. A. N. Kirpichnikov says the following about the sword in question: “The finely crafted bronze handle with a textured handle looking like tangled monster bodies is similar to the Scandinavian adornments of the XI century. Every research publication refers to it as to a Scandinavian sword discovered in Russia” ([385], page 54).

A. N. Kirpichnikov tells us further: “In the XII century the marking technique changed. The new ornaments were lined in brass, silver and gold. The actual markings changed as well – the smiths’ names . . . were replaced by long chains of letters . . . Most of such inscriptions, including the ones that we found, remain sans interpretation” ([385], page 50).

Where were most of these findings made? We have deliberately forborne from studying this issue in greater depth. The following selection of swords may nonetheless give one an idea about the distribution of the findings – the inscriptions upon them are abbreviated. The data were taken from [254], page 17.

“A complete list of the swords with abbreviated inscriptions comprises 165 items . . . if we are to take into account the sites of the findings, or, in cases when those remain unknown, the places where they are kept, the findings are distributed across the European countries as follows:

USSR – 45 (Latvia – 22, Estonia – 7, Ukraine – 6, Lithuania – 5, Russia – 5), East Germany – 30, Finland – 19, Switzerland – 12, West Germany – 12, Poland – 11, Czechoslovakia – 9, France – 8, Great Britain – 6, Denmark – 5, Norway – 4, Spain – 2, Sweden – 1, Italy – 1)” ([254]), page 17).

As we can see, most of the findings were made in USSR and its closest neighbours and not in Scandinavia.

There are many swords – thousands, no less, that haven’t been furbished to date ([385], page 55). Furthermore, “only a tenth of the four thousand swords dating from the VIII-XIII century kept in various European collections has been studied” ([385], page 55).

What is written on the swords exactly? As we have already found out, modern historians are hardly capable of reading the lettering with confidence. This is easy enough to understand – the inscriptions are in fact strings of letters that whimsically combine Cyrillic and Roman characters as well as other symbols. For instance, in [254] we can only see two more or less sensible interpretations of names: Constantine and Zvenislav ([254]). The first name is international, and the second, typically Slavonic.

Other incomprehensible sequences of characters are usually interpreted in the following manner. Each character is presumed to stand for the first letter of some Latin word, which implies that the entire inscription is an acronym. However, this point of view makes it rather easy to interpret any sequence of symbols in any given language.

Also, the researchers are for some reason certain that most swords hail from the Western Europe, hence the tendency to interpret symbols and series of symbols within the confines of the Latin language. Interpreting (or misinterpreting) said symbols as Romanic characters, the researchers transform them into lengthy texts of a religious nature.

Let us cite a typical example from [254], which is the inscription on a sword found near the village of Monastyrishche in Voronezh Oblast, qv in fig. 3.1. The photograph was taken from A. N. Kirpichnikov’s article in [385]. The interpretation suggested by Dbroglav is as follows. First he converts the symbols into Romanic characters, coming up with NRED – [C] DLT as a result. Then he gives the following Latin interpretation of this alleged acronym: N [omine] Re [demptoris] D [omini] (C [hristi]) L [igni] T [rinitas]. See [254], Table VII (“NR” group).

The translation is as follows: “In the Name of the Redeemer – the Lord and the Cross of Our Lord Christ. The Trinity” ([254], Table VIII).

The letters in round brackets were added by Dbroglav. We have already related our sceptical opinion of this “interpretation method” applied to incomprehensible inscriptions as suggested by the learned historians. We are of the opinion that the problem of interpreting obscure inscriptions found on swords and coins is of the greatest interest – possibly also of tremendous complexity. It needs to be formulated explicitly and solved. Basically, it can be rendered to a well-known problem of decipherment; such problems are successfully solved by experts in this field, who also use mathematical methods.

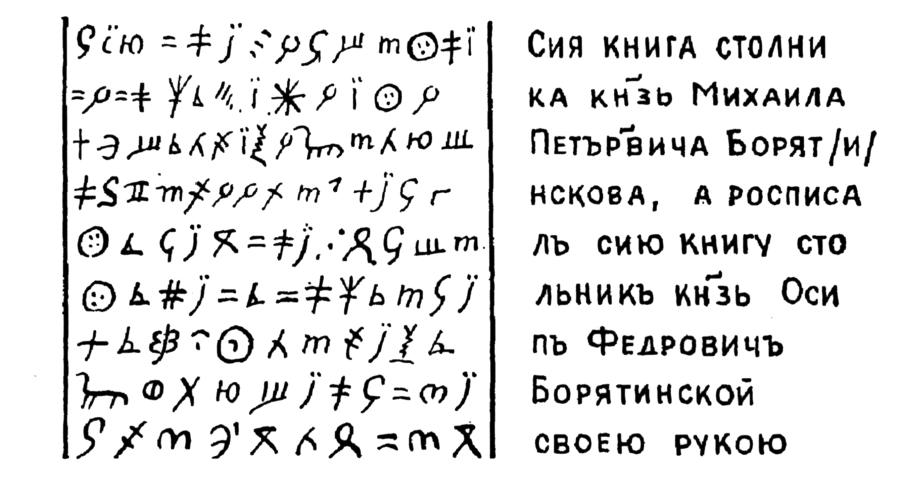

We haven’t conducted a study of the actual problem. Nevertheless, we must voice a certain consideration that might be of use in the future. The so-called “cryptographic writing”, or letterings employing letters that strike us as uncanny nowadays, appears to have been very common before the XVII century, in Russia as well. There are indubitable interpretations of some such inscriptions in existence, including the one found in a Russian book of the XVII century that was deciphered by N. Konstantinov ([425]). We already mentioned it in CHRON4, Chapter 13:6. This Russian inscription had also been considered indecipherable by historians for many years. We reproduce it once again in fig. 3.2, and in 3.3 one sees the symbol decipherment table suggested by N. Konstantinov ([425]).

Let us apply the same table to the lettering on the sword that we have just mentioned. We shall come up with the following: SIKER (or SIKERA), a division mark, and another word that reads as VOPE or NOVE. The second part of the inscription remains obscure – however, the first word is clearly “sekira”, which is the Russian for a special type of sword. This goes to say, the inscription is in Russian and not in Latin; also, the sword was found in the Voronezh Oblast.

Now we shall proceed with applying this method to all the drawn copies of the inscriptions found on swords as reproduced in the article of A. N. Kirpichnikov. There are four of them. The first one has just been discussed (see figs. 3.1 and 3.4). A. N. Kirpichnikov provides a reproduction of the sword’s reverse side, whereupon we see a tamga (fig. 3.4) – the “Tartar” symbol that we already know well enough and have discussed in detail.

The remaining three contain the names of the mysterious Western European smiths, presumably in Latin. Bear in mind that they have never been known to anyone in the Western Europe, qv above.

Inscription #2 is reproduced in fig. 3.5. A. N. Kirpichnikov suggests to read it as “CEROLT”. There is no such word in the Latin dictionary ([237]). Therefore, it is suggested to consider the word to be the name of a craftsman. Let us note that this “method” allows interpreting any incomprehensible acoustic pattern as an old and forgotten name. However, the application of N. Konstantinov’s table yields the word “SORDTSE”. The letter “Ts” is missing from the table, but we have reconstructed it from the context. This doesn’t contradict N. Konstantinov’s table. The resulting word is the archaic version of the Russian word for “heart” (“serdtse”) – it is perfectly apropos on a sword. On the reverse of the sword we see the Russian (or Tartar) tamga once again.

Inscription #3. See fig. 3.6. A. N. Kirpichnikov suggests to read it as a sequence of Romanic characters once again, which yields “ULEN”. There is no such word in Latin ([237]); name-wise, it resembles the Slavic name Oulian the most. Konstantinov’s table yields “ISON” or “YASON” (resembles “yasniy”, or “clear” – also a fitting word to put on a sword.

Inscription #4. It can be seen in fig. 3.7. A. N. Kirpichnikov suggests reading the characters as Romanic, coming up with “LEITPRIT”. This word doesn’t exist in the Latin language ([237]). The application of Konstantinov’s table gives us “TSESTARIE” (or “TSESTANIE”). It resembles the archaic Russian word “tsestit”, or “to clean” (see M. Fasmer’s dictionary, [866]). The inscription can therefore translate as “clean”, or “pure” – “pure steel”, “clean weapon” or something along those lines. On the reverse we see the symbol that stands for the letter “B”, according to the table.

We do not imply our interpretation to be correct. Four brief inscriptions hardly suffice for any conclusions at all, especially seeing how we had to decipher sequences of barely understandable symbols. We are simply trying to attract the readers’ attention to the problem and point out the possible uniformity of the “cryptographic” inscriptions on coins, swords, books etc. It is most likely to have nothing “cryptographic” about it, simply being an old forgotten alphabet used in Russia, and, possibly, other places as well – Western Europe, for instance, up until the XVII century or even later.

Fig. 3.9. A close-in of a tamga as used by the “Mongol” Horde

on the hilt of an ancient Viking sword. Taken from [264], Volume 1, page 488.

Finally, let us quote from A. N. Kirpichnikov’s article: “In Russian science the swords . . . provoked a revolution in scientific thought. The majority of the debates concerned the origins of the swords – some regarded them as weapons used by the Norman invaders, who had conquered the Eastern Europe and colonized the Slavs. Others objected, and justifiably so, that the swords were used all across Europe by Normans as well as the Slavs [in Part 3 we shall learn about the two identifying as the same nation – Auth.]. The debates became more heated over the course of time – the findings of swords classified as “Varangian” led a number of scientists to the hypothesis that the first state of the Eastern Slavs, or Kiev Russia, was founded by the Normans” ([385], page 51).

It is possible that the Varangian (Norman) swords were forged in Tula, or Zlatoust (a city in the Ural region). In fig. 3.8 we see a handle of a Viking sword with a “Mongolian” tamga, qv in fig. 3.9.

2. Italian and German swords with Arabic lettering.

Fig. 3.10. Italian sword with Arabic lettering. ROM Museum of History,

Toronto, Canada. Photograph taken in 1999.

In July 1999 about a dozen of Italian and German swords of the XIII-XIV century were exhibited in the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada. Two of them can be seen in figs. 3.10 and 3.11. One cannot help noticing that Italian and German swords are decorated with Arabic lettering, for some reason lacking so much as a single word in either German or Italian (at least, we haven’t found anything of the kind).

Historians have noticed this circumstance a long time ago – it is rather odd as seen from the Scaligerian viewpoint, after all. After some consideration, they came up with an “explanation”, which was put on the notice plate next to the swords. The suggestion is that “the Arabic lettering indicates that the sword in question was stored in the arsenal of Alexandria, Egypt”. In other words, the Italian and German swords somehow ended up in the Egyptian city of Alexandria, where they were taken to the Arsenal and decorated with Arabic lettering. This strikes us as odd – the lettering was most likely made during the forging of the swords, on hot steel. It must indicate the same as the Arabic lettering on the ancient Russian armaments, as discussed in CHRON4, Chapter 13:10 – namely, that in the XIV-XVI century the idiom known as Arabic today counted among the languages spoken all across the Great = “Mongolian” Empire, which had comprised Italy and Germany.

3. The reason why the coronation mantle of the Holy Roman Empire is covered in Arabic lettering exclusively.

In fig. 3.12 one sees the famous coronation mantle of the Holy Roman Empire. We have found a representation thereof in the section of [336], Volume 6 (inset between pages 122 and 123) entitled “The Regalia of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation” – the book is a rare oeuvre of the XIX century. German historians wrote the following: “The royal German regalia, or insignia, are the garments usually worn by the German king or emperor during coronation or on other festive occasions as symbols of his royal power . . . some of them have gone missing; however, most of the objects, including the most important ones, have survived until the present day” ([336], Volume 6, pages 122-123).

Fig. 3.12. Coronation mantle of the Holy Roman Empire.

From the Scaligerian viewpoint it is truly amazing that

the only lettering found on the item is Arabic.

Taken from [336], Volume 6, inset between pages 122 and 123.

Fig. 3.16. Mantle of Charlemagne.

Kept in the Aachen Cathedral. Decorated with Ottoman = Ataman

crescents and crosses. Taken from [1231], page 19.

Fig. 3.17. A close-in of the Imperial eagle on the mantle

of Charlemagne. We see Ottoman = Ataman crescents

on the eagle’s chest. Taken from [1231], page 19.

It is most amazing as regarded from the Scaligerian viewpoint that there’s an Arabic inscription on the coronation mantle of the Holy Roman Empire. There’s no other lettering anywhere upon it. Thus, the mediaeval rulers of the Holy Roman Empire wore a ceremonial mantle covered in Arabic lettering – not “German” (see figs. 3.13, 3.14 and 3.15).

Scaligerite historians are trying to find some sort of an “explanation” to this fact, which naturally strikes them as surprising – they do it in the following clumsy manner: “According to the Arabic inscription found near the fringe of the mantle, it was made in the 528th year of Hejirah, or 1133 A. D. [allegedly – Auth.] in the “happy town of Palermo” for Roger I, King of Normandy; it must have been taken away from the Norman trophies of Henry VI after some of the imperial regalia had perished in the storm of Vittoria and placed in the imperial treasury” ([336], Volume 6, pages 122-123). In other words, we are told that the emperors solemnly started to use this “foreign Arabic mantle” instead of their own “perished German regalia” – it hadn’t occurred to them to make a new German mantle, or, perhaps, the emperors of the Holy Roman Empire didn’t have the money necessary to make a new coronation mantle to replace the one that perished, preferring to wear a second-hand import instead.

We believe the picture to be crystal clear – what we see is the very same effect as we have noticed in case of the countless “Arabic inscriptions” on the ancient Russian weapons. It is most likely that the coronation mantle of the Holy Roman Empire had been worn by the local rulers of Germany, a province of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire, regnant on behalf of the main Russian Czar, or Khan of the Horde. The mantle was obviously covered in “Mongol” lettering as a symbol of the “Mongolian” Empire, which was subsequently declared “exclusively Arabic” by the historians. However, back in those days the most important documents and inscriptions were written in Slavic as well as in “Arabic”.

Incidentally, historians also report that the precious regalia of the Holy Roman Empire include “the so-called sabre of Charlemagne, an oriental antique” ([336], Volume 6, pages 122-123). Although it isn’t depicted in [336], one gets the obvious idea that this sabre might be decorated with Arabic lettering, likewise the Russian weapons of the Middle Ages.

Let us now regard the luxurious ceremonial mantle of Charlemagne (fig. 3.16). It is nowadays kept in the treasury of the Aachen Cathedral in Germany. It is presumed to have been made around 1200 ([1231], page 19), although Scaligerian history presumes Charlemagne to have lived several centuries earlier. Therefore, historians make the following evasive comment in this respect: “The mantle has been worshipped in the Cathedral of Metz as the Mantle of Charlemagne ever since the XVII century” ([1231], page 19). It is most noteworthy that Charlemagne’s mantle is decorated with crosses and Ottoman (Ataman) crescents. The large crescents were placed on the chest of the imperial eagle in particular, qv in fig. 3.17.

4. Church Slavonic inscription in the glagolitsa script in the Catholic Cathedral of St. Vitus in Prague.

Fig. 3.18. Photograph of the Orthodox cross with a Church Slavonic inscription rendered in the glagolitsa script from the Catholic Cathedral of St. Vitus in Prague. Photograph taken by G. A. Khroustalyov in 1999.

In fig. 3.18 we reproduce a modern photograph made in the Catholic cathIn fig. 3.18 we reproduce a modern photograph made in the Catholic cathedral of St. Vitus (Prague) by G. A. Khroustalyov in 1999. Deep in the inner reaches of the cathedral, to the left from the main entrance, one sees an Orthodox cross carved in wood with an inscription upon it, which is, oddly enough, in Church Slavonic (see fig. 3.19). The script used is the glagolitsa (see fig.3.20), which is somewhat older than the Cyrillic alphabet. The inscription translates as “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God”.

This is how the Gospel according to John begins [the original contains the Church Slavonic version of the phrase – Trans.] – thus, we see a Church Slavonic inscription in a Catholic cathedral in Prague. However, we are told that Prague has always been a Catholic city, ditto the Cathedral of St. Vitus, which theoretically means that all the inscriptions found therein should be in Latin.

From our reconstruction’s point of view, there is nothing odd about the Church Slavonic inscriptions in the Catholic cathedrals of the Western Europe. There must have been much more of them before the XVII century – as we can see, some have even survived until our day and age.

Let us formulate the following theory about the name of Prague’s main cathedral. It is possible that St. Vitus of Prague can be identified as Batu-Khan. As we point out in CHRON4 and CHRON5, the name Vatican may also be a derivative of Batu-Khan. The same root could have transformed into Vitus. As for the frequent flexion of B and V, it is a known fact in linguistics.

5. The peculiar title of Alexei Mikhailovich Romanov, a Russian Czar of the XVII century, as inscribed on his seal.

Fig. 3.22. A close-in of the inscription on the seal

of Czar Alexei Mikhailovich with the words

“Lord and Sole Ruler of our Father’s

and Forefathers’ Lands of the Eastern and Western Infidels”.

Taken from [960], page 20.

A. S. Chistyakov’s book entitled “The History of Peter the Great” contains a reproduction of an old seal used by Czar Alexei Mikhailovich, the father of Peter the Great ([960], page 20, fig. 3.21). There is a long string of text placed along its rim, which translates as follows:

“We, the Great Ruler by God’s Mercy, Czar and Great Prince Alexei Mikhailovich, Liege of the Entire Greater, Lesser and White Russia, Heir, Lord and Sole Ruler of our Father’s and Forefathers’ Lands of the Eastern and Western Infidels”.

The inscription is of the greatest interest indeed. Apparently, Alexei Mikhailovich ruled over the Eastern and even the Western states and lands apart from the Lesser and White Russia – lands of the infidels, as it were, which is what his seal of state claims (see fig. 3.22). Apart from religious differences, this word is also likely to mean that the countries in question had no longer been part of the Empire. He is also said to be the owner of said lands by inheritance, since, according to the seal, they had once belonged to his “father and forefathers”. This title must date back to the pre-Romanovian Czars (or Khans) of Russia, or the Horde – the epoch when the Great = “Mongolian” Empire spread from the British Isles to Japan, and even America, qv in CHRON4, Chapter 12, and CHRON6, Chapter 14.

The modern version of Russian history makes this version of the seal look very strange and extremely pompous. What exactly is Alexei Mikhailovich referring to when he claims on his seal of state, no less, that his forefathers reigned over many “infidel” lands to the west and the east of Russia? The Scaligerian and Millerian version of history makes these claims sound outrageous. Historians will naturally suggest some “theory” to explain this – namely, that Alexei Mikhailovich was a great eccentric, fully aware of the fact that his ancestors had never reigned over such a multitude of remote territories, but the alleged custom of the epoch stipulated making unjustified claims of this kind.

Our reconstruction explains this perfectly well – indeed, in the epoch of Alexei Mikhailovich the memory of the lands recently owned by the Czars (or Khans) of the pre-Romanovian epoch had still been very much alive.

Another thing to say about the seal of Alexei Romanov is that we see six cities to the left and to the right of the bicephalous eagles – in the right part of fig. 3.21 they are marked V, Z and S, and in the left – V (or Ts, the reproduction isn’t quite clear), M, and R. One wonders about what cities these might be exactly.

Below, to the left and right of the eagle, we see armed warriors. They appear to be divided – one army is depicted on the left, and the other, on the right. This could be a reference to the Western and the Eastern Hordes of the Empire. Underneath the eagle’s paws we see two ornaments that resemble the Ottoman (Ataman) star and crescent symbol to a great extent.

6. Stone effigies on ancient Russian grave-mounds. The “stone maids of the Polovtsy”.

According to historian G. Fyodorov-Davydov, “ancient stone effigies can be found in nearly every historical museum of the Russian south: in Rostov, Novocherkassk, Azov, Krasnodar, Stavropol and the cities of the Crimea. They are abundant – hundreds of stone statues . . . They are just as monumental and mysterious as the enigmatic idols of the Easter Island . . . Researchers are still debating the identity of their creators, as well as the purpose of their making” ([871], page 74).

Apparently, “these stone idols had originally stood on grave-mounds and hills, and were then taken to peasants’ plots of lands and to landowners’ estates, later to be exhibited in museums or installed in provincial parks for amusement” ([871], page 74).

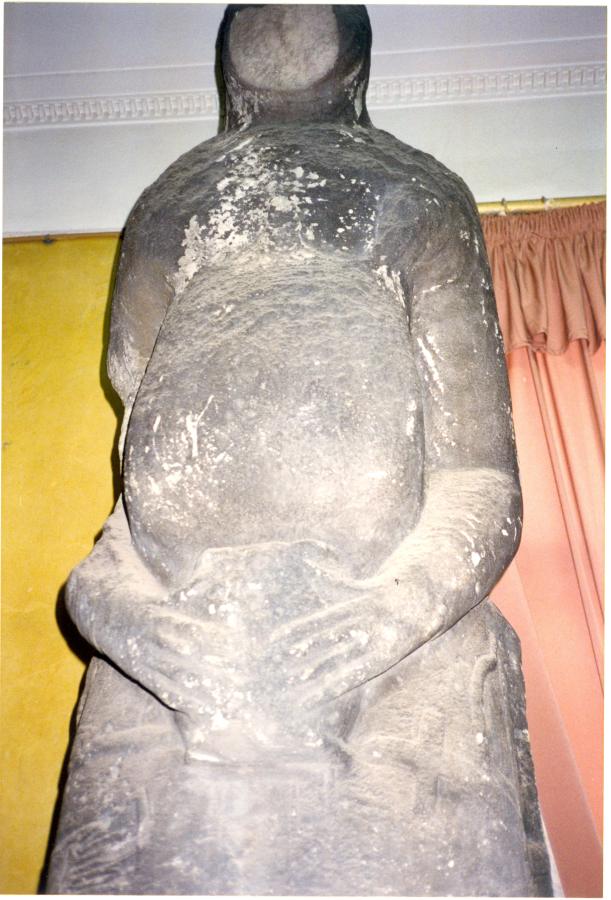

“In the XVIII century they were called ‘stone men’ or ‘stone maids’” ([871], page 74). Such statues weren’t only found in the south – discoveries were also made in the vicinity of Moscow (in Kuntsevo and in Zenino, according to the “Readings of the Imperial Society of History and Russian Antique Studies at the University of Moscow, 1870, Volume III). Kuntsevo lay to the west of Moscow, and Zenino – 21 verst (1 verst = 1.3 miles) as of 1870. One of the effigies stands in the reception hall of the Russian National Library and can be seen by anyone (see figs. 3.23 and 3.24). It was brought to Moscow by request of the Imperial Society of History and Russian Antique Studies (as mentioned above) in 1839.

Fig. 3.23. Stone statue of a warrior originating from the Horde and known

as “Stone Maid of the Polovtsy” courtesy of modern historians.

Currently located in the reception hall of the State Library of Russia, Moscow.

Photograph taken by A. T. Fomenko in 1995.

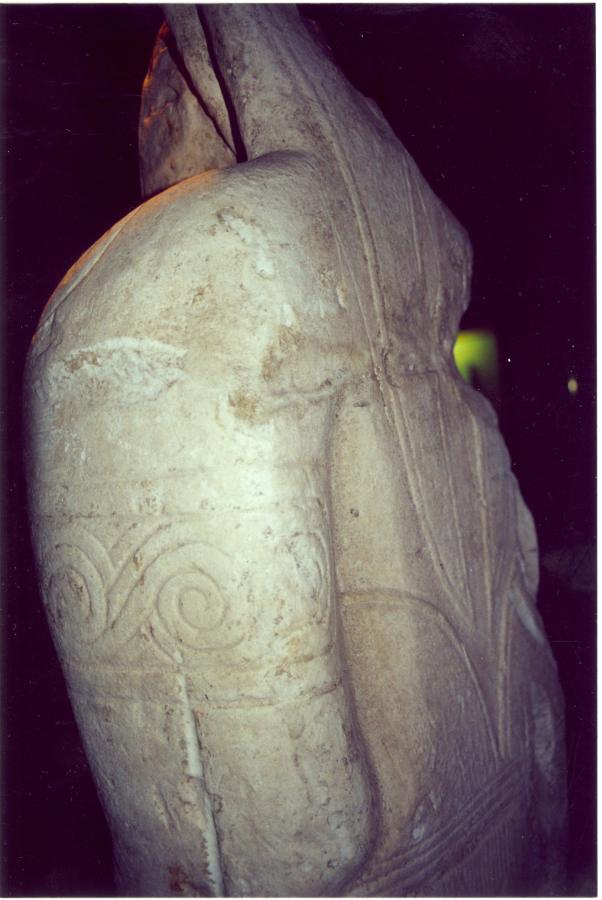

Fig. 3.26. Russian military Cross of St. Andrew (X-cross) on the back of the Horde stone statue

. Photograph taken in 1995.

A distinctive characteristic of these effigies is “the vessel, cup or horn that they hold pressed against their stomachs” ([871], page 76). The statue exhibited in the hall of the Russian National Library is no exception (see fig. 3.25). There is a large X-shaped cross on its back (see fig. 3.26). This cross is known as the Cross of St. Andrew. Ever since the epoch of Peter the Great, banners with such crosses have been used by the Russian navy ([797], page 58). By the way, on the side of this male effigy we see a scimitar as well as a bow and a quiver of arrows (see fig. 3.27). These armaments were indeed typical for Russian warriors – up until the XVII century.

Ever since the epoch of the Romanovs, historians have adhered to the opinion that these statues were vestiges of the conquest of Russia by the foreign tribes of the Polovtsy. A historian writes: “For the Russians, these stone monsters symbolised the dominancy of the Polovtsy over the steppes, which is why they were very prone to destroying and defacing these statues” ([872], page 76). We are already well familiar with this trend of systematic defacement, which has affected the Russian sarcophagi, the Egyptian statues, carvings in stone etc. Who could have been offended by them? Hardly the local populace.

The modern opinion is that the Polovtsy, or the invaders who built the statues, had come to Russia from afar – the Mongolian steppes, Tuva and Altai ([871], page 75). We are told that as the Polovtsy moved further west, these “stone maids” spread all across Russia.

We are of the opinion that the “stone maid mystery” is nonexistent – it only results from the fact that the Romanovs replaced many of the ancient Russian customs, including the funereal rites, by new ones, which has led to the false assumption that the latter have existed in Russia since times immemorial. Moreover, many of the Russian chronicles were either written or heavily edited under the Romanovs. Many of the documents were destroyed. The remaining meagre selection of chronicles was declared mind-bogglingly ancient. It has become conventional to consider any custom left outside the scope of these “Romanovian antiquities” foreign and untypical for Russia; every remaining trace of such customs was declared to have been left by foreign invaders.

Here is a typical example of such thinking. It is known that most of the stone effigies considered herein were found in Russia. However, “one encounters them in the East as well – in the vast steppes of Kazakhstan, Altai, Mongolia and Tuva” ([871], page 75). This leads the learned historians to the conclusion that Russia was conquered by invaders from Mongolia, the most distant of these lands, who are said to have conquered Kazakhstan, Altai etc “en route”. Consider this: “In the beginning of the second millennium the Polovtsy made a breakthrough to the West. They marched through Kazakhstan quickly, and came to the Volga region in the middle of the XI century” ([871], page 75).

Our reconstruction arranges things in the correct order. The direction of the expansion had been the reverse, and it was started by the Russians, who had also conquered territories in the East. This becomes obvious from the following simple observation alone.

It turns out that the stone effigies of the “Polovtsy” found in the steppes of Kazakhstan, Altai, Mongolia and Tuva are “male as a rule . . . often with a drooping moustache [characteristic for the Cossacks, as a matter of fact – Auth.]” ([871], page 75). However in Russia “more than 70 per cent of the earliest Western statues [found in Russia and not in the East – Auth.] of the Polovtsy are female. We are confronted with a mystery that still defies a scientific explanation [sic! – Auth.]” ([871], page 76).

We have to admit that there is nothing mysterious about this fact – it simply reveals the location of the homeland of the warriors who erected these statues. It is obvious that in their homeland (Russia) the statues on grave-mounds were of both sexes, since the land had been inhabited by both men and women. However, very few women took part in the military campaigns. The male warriors died and were buried on the spot, without transporting the bodies back to the distant motherland. Therefore, the statues erected in the conquered territories must have been almost exclusively male, which is exactly the case with Kazakhstan, Altai, Tuva, Mongolia etc. Actually, the suggestion that the statues were built by the “Polovtsy” might be derived from the fact that they were built in the fields (cf. the Russian adjective for “field” – polevoy).

Therefore, we are of the opinion that the stone effigies of the “Polovtsy” are simply the ancient Russian memorial monuments.

Actually, one cannot fail to pay attention to the bizarre fact that the parts of the statues that actually got chiselled off are the faces – we see this to be the case with the statue in the Russian National Library as well as the photographs of the statues available to us. Why the faces? Could it be that they looked explicitly Slavic?

We have a direct mediaeval piece of evidence about the “Mongolian” (or Russian, as we realise today) origins of the statues’ makers. According to G. Fyodorov-Davydov, “William of Rubruck, a monk from the Western Europe who travelled to the faraway Karakorum in central Mongolia [or central Russia, according to our reconstruction – Auth.], the capital of the Mongol khan, in the middle of the XIII century, leaves some interesting evidence . . . Among other things, Rubruck reports the following: ‘The Komans mount large mounds over the deceased and install statues upon them, facing east and holding chalices near their stomachs’” ([871], page 75).

It is hard to disagree with the historians’ opinion that Rubruck is referring to the very “stone maids of the Polovtsy”, taking the chalices into account. As for the “Mongolian Komans”, they are most likely to identify as horsemen, seeing as how the archaic Russian word for “horse” was “komon” (see the “Tale of Igor’s Campaign”, for instance).

Stone effigies of the Scythians weren’t just found in the East – they also exist in Europe. In fig. 3.28 one sees a male statue carved in stone, which is “the idol of the Scythian sanctuary . . . installed upon the ancient grave-mound of Tsygantcha over the Novoye Selo ford across Lower Danube” ([975], page 736).

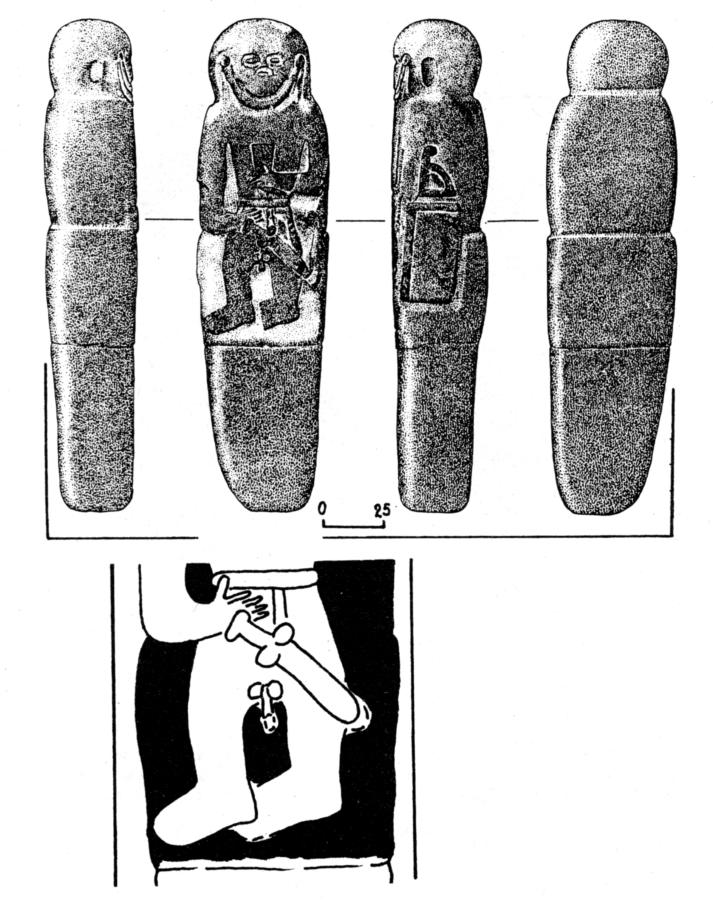

In figs. 3.29, 3.30, 3.31 and 3.32 we see a stone statue of a female, which is kept in the State Hermitage of St. Petersburg. We find the following legend on the notice plate: “An effigy of the Polovtsy, XII century, Krasnodar region”. The face of the statue is disfigured; it is holding a chalice against its stomach and has a hood that falls over its back.

Fig. 3.28. Stone statue of a Scythian warrior with a sword. Tsygantcha Mound, Lower Danube. Archaeologists date it to the V-IV century B. C. As we realize today, they are wrong. Taken from [975], page 736, ill. 57.

Fig. 3.29. A stone effigy made by the Polovtsy.

Front view. The Hermitage, St. Petersburg. Photograph taken in 2000.

Fig. 3.30. A stone effigy made by the Polovtsy.

Side view. The Hermitage, St. Petersburg. Photograph taken in 2000.

Fig. 3.31. A stone effigy made by the Polovtsy . Rear view.

The Hermitage, St. Petersburg. Photograph taken in 2000.

Fig. 3.32. A stone effigy made by the Polovtsy. Head of the statue.

The Hermitage, St. Petersburg. Photograph taken in 2000.

In fig. 3.32a we see a stone statue from the National Museum of History in Moscow. It is a female figure with a “chalice” held close to its stomach. A propos, there is no notice plate anywhere near it, so we know nothing of where the statue was discovered. Could it be Moscow? The absence of plates can be explained by the fact that, according to Scaligerian and Millerian history, the Polovtsy never lived in the region of Moscow, therefore it is somewhat incongruous to make such findings here.

>In fig. 3.32b we see ancient stone statues built by the Horde in the Altai region of Xinjiang, China.

Fig. 3.32a. Ancient Scythian stone effigy exhibited

in the Moscow State Museum of History.

The statue is female, and holds an object that is

considered to be a chalice pressed against its stomach.

There is a hat on the head of the statue;

it also appears to have braids.

Fig. 3.33. Ancient stone

effigy of the deity Chac Mool.

America, Yucatan.

The statue is virtually identical

to the ones made by the Polovtsy,

or the Scythians

(they look as human figures

holding chalices against their stomachs). Taken from [1056], page 9.

Fig. 3.34. Ancient stone effigy of the deity Chac Mool

at the entrance of the Warrior Temple in Chichen-Itza.

Human figure with a chalice held at stomach level.

Taken from [1056], page 34.

Fig. 3.35. A close-in of a statue that portrays

a deity worshipped by the Mayans and the Toltecs.

The primary motif is the same as in case of the Scythian statues.

The statue holds a chalice near its stomach.

Taken from [1056], page 34.

Let us point out the detail that characterises most of these Scythian effigies – they all hold some object near their stomach, which is considered to be a chalice. It is most noteworthy that some of the statues found on the American continent (the “ancient” Toltec and Mayan territories, for instance) look strikingly similar. In fig. 3.33 we see a photograph of one such statue from Yucatan (Merida Museum). It is presumed that such stone effigies were made by the Mayans and the Toltecs ([1056], page 9). The human figure here is reclined and holding a large flat chalice against its stomach. Another ancient Toltec effigy of stone can be seen in fig. 3.34 – it is also shaped as a reclining human figure, the god Chac Mool that holds a chalice pressed to its stomach (fig. 3.35). The statue is located in Chichen Itza, near the entrance to the large “Warrior Temple” ([1056], pages 34-35). Let us point out that these statues were treated with respect in America – as deities, no less.

The positions of the Scythian and American statues are different; however, the main motif, or the chalice held near the stomach, is the same for both types. The reason such duplicates exist is very simple – we see traces of a common culture that emerged as a result of the XV century conquest of the Americas by Russia (or the Horde) and the Ottoman (Ataman) empire. The colonists had brought their customs with them. See CHRON4 and CHRON6 for more details.