Part 2.

China. The new chronology and conception of Chinese history. Our hypothesis.

Chapter 7.

The Great = “Mongolian” conquest of Japan.

1. The military caste of the Japanese Samurai as the descendants of the XIV-XV century conquerors of Japan originating from the Horde.

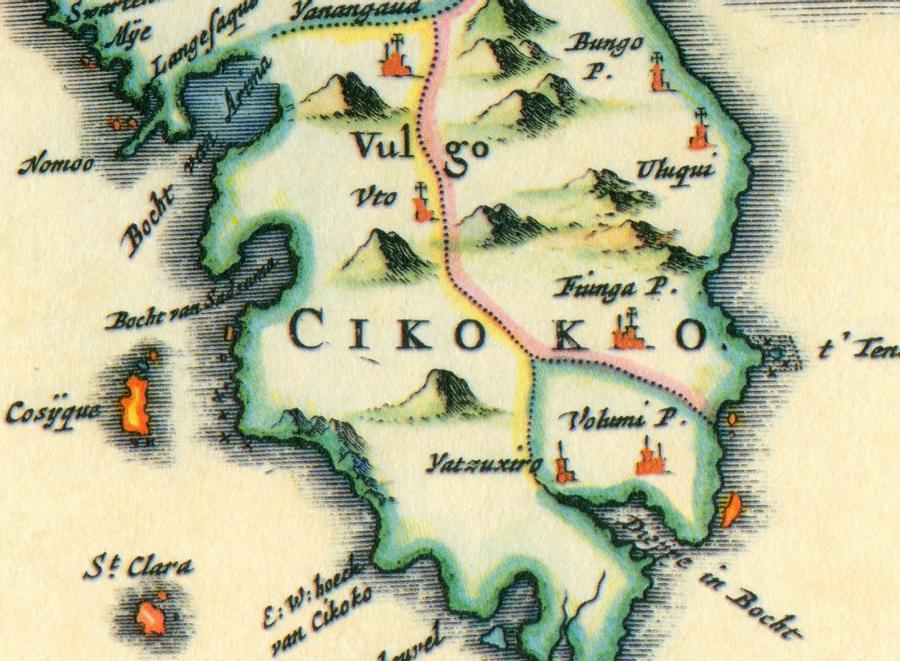

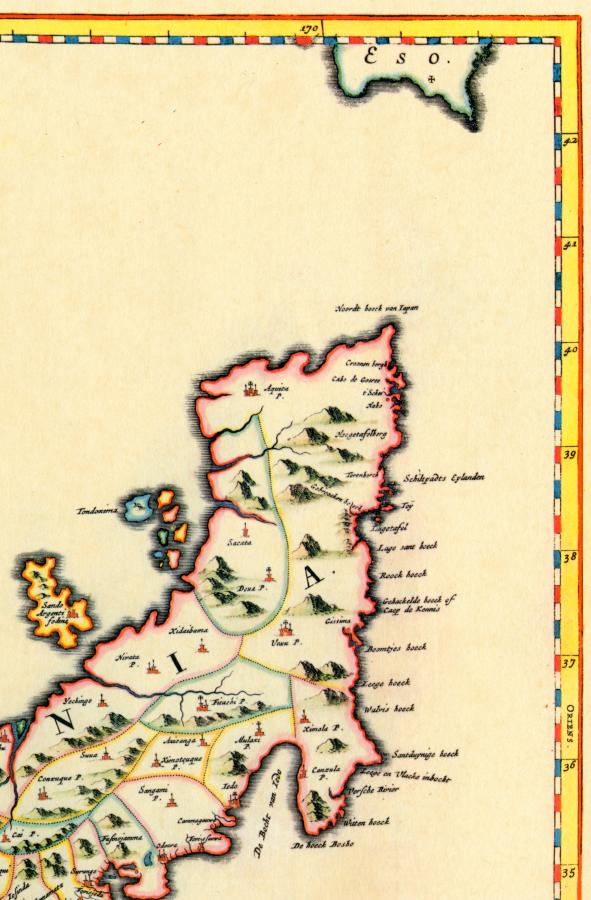

Above we have cited certain data to support the idea that Japan was also conquered by Russia, or the Horde, during the epoch of the Great = “Mongolian” conquest. The military reign of the Samurai = Samarians is most likely to identify as the reign of the Horde established on the Japanese Isles after their conquest. In particular, as we have pointed out above, many representatives of the Horde from Muscovite Tartary and the American Northeast relocated here after the defeat of “Pougachev” in the second half of the XVIII century. Are there any traces of the Great = “Mongolian” conquest of Japan in existence? There are indeed. Let us turn to the old maps of Japan – for instance, the one from the famous atlas of John Blau, presumably published in 1655 ([1035]). See figs. 7.1 and 7.2.

In the South of Japan we see two islands under the name of Gotto. It is likely to be derived from the word “Goth” (see fig. 7.3).

Apart from these, we see an island called Cosyque (the word is possibly derived from the word Cossack, qv in fig. 7.4). Nowadays the island in question is called Kyushu ([507], map 97-98). The name KAS (KAZ) must be a slightly distorted version of GUZ, which is a name that used to stand for “Cossack”.

We also see the name Vulgo on a bigger island nearby – a possible derivative of “Volga” or “vlaga” (the Russian for “wet” or “water”), qv in fig. 7.5.

Nearby we see the legend “Cikoko” in large letters (fig. 7.5). We instantly recollect the old name of Scotland, or “Scocia” (see CHRON4, Chapters 15-18). Both names might be derived from the Russian words for “gallop” and “ride” (“skok” and “skakat”). It could have been used for referring to horsemen, or the Cossacks. The name of the famous Japanese city of Osaka might also be a derivative of the word “Cossack”. One of the largest islands in Japan is still called Sikoku ([507], map 97-98).

The name of another famous Japanese city, Kyoto (the old capital of Japan) is virtually identical with the names “Kitia”, “Kitai” and “Scythia”. As a matter of fact, the name of Japan’s current capital, or Tokyo, reads as “Kyoto” if we reverse the order of the syllables. In Japanese, the two names consist of two hieroglyphs each, and only differ in order. Let us remind the reader that the capital was transferred from Kyoto to Tokyo.

Nagoya, the name of another Japanese city, may have appeared on the Japanese Isles as a trace of the famous Nogai horde, since the Nogai Cossacks must also have taken part in the conquest of the Japanese Isles.

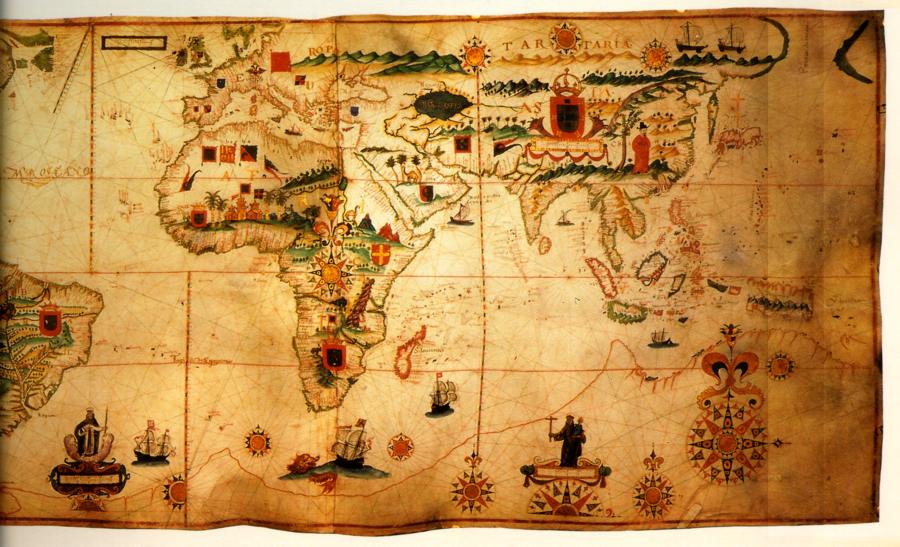

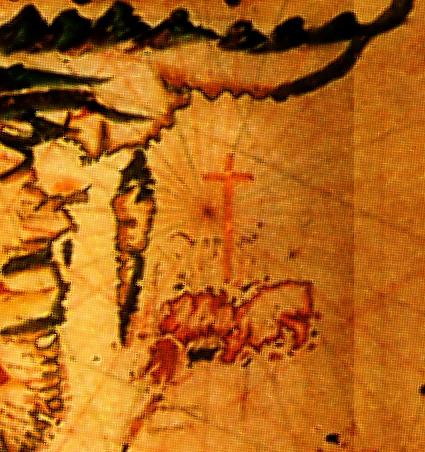

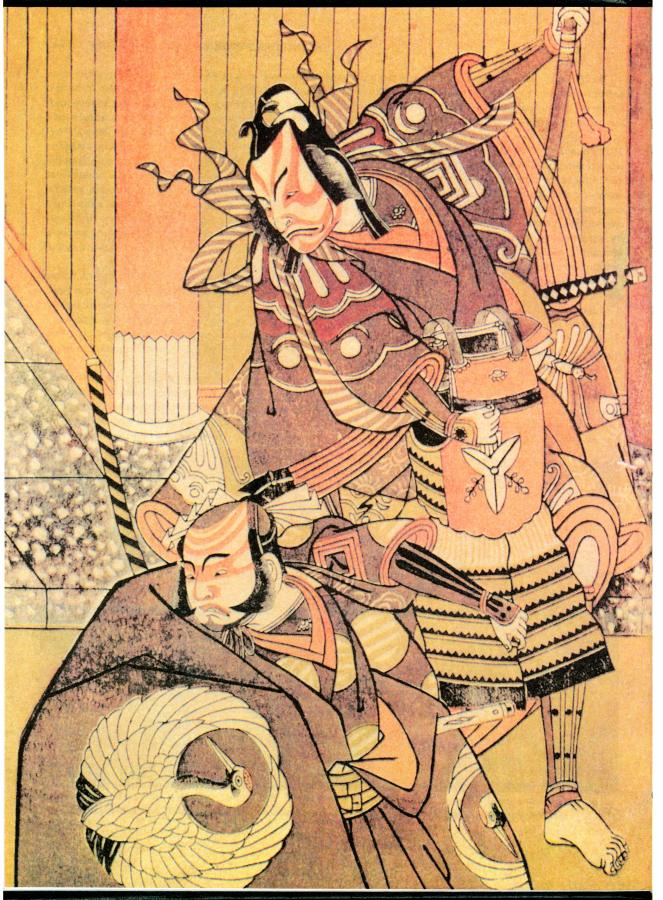

Let us now turn to another old map, which dates from the alleged year 1623 (of Portuguese origin – see [1027], map 14, and fig. 7.6). One’s attention is instantly drawn to the Japanese Isles and the gigantic Christian cross upon them, qv in figs. 7.7 and 7.8. This fact blatantly contradicts Scaligerian history – basically, it tells us that the Portuguese cartographers of 1623 considered Japan a Christian country in the first half of the XVII century. Scaligerian history tells us nothing of this sort. The fact that Japan was a Christian country in the XVII century is explained perfectly well by our reconstruction, according to which the military dynasty of the Samurai = Samarians, or the “Mongols” hailing from Russia, or the Horde, had still reigned in Japan in the early XVII century. They had still worn Ottoman crescents on their helmets, and adhered to the Christian religion. Photographs of Ottoman crescents on the helmets of the mediaeval Samurai can be seen in figs. 7.9, 7.10, 7.11 and 7.12. The Ottoman = Ataman crescents also decorated the clothes of the Samurai, qv in figs. 7.13 and 7.14. One must also pay attention to the Samurai coat of arms in the bottom left corner of the engraving in fig. 7.15. It is a version of the imperial eagle, or the star (cross) and crescent symbol. A most symbolic circumstance is that this ancient military crest of the Samurai (fig. 7.16) is placed on the title pages of both volumes of the famous Harper’s Encyclopaedia of Military history (the Russian edition is known as the World History of Wars – [264]) as a generalised symbol of war.

All of the abovementioned facts are also most likely to testify to the fact that the Japanese Isles were also caught in the wave of the Great = “Mongolian” conquest of the XV-XVI century.

Actually, our visual concept of the Japanese Samurai in the epoch when they were still a secluded military ruling caste in Japan. According to modern art and cinema, they had looked just like the modern Japanese – perfectly Asian, in other words. Let us remind the reader that there was a revolution in Japan in 1867-1868. It resulted in the fall of the Samurai power; their remnants became mixed with the rest of the populace ([797], pages 849 and 1571). Nowadays the descendants of the Samurai look just like the rest of the Japanese. However, this appears to be untrue. Before their assimilation, the Samurai appear to have belonged to the European race. This conclusion was made from the following circumstance.

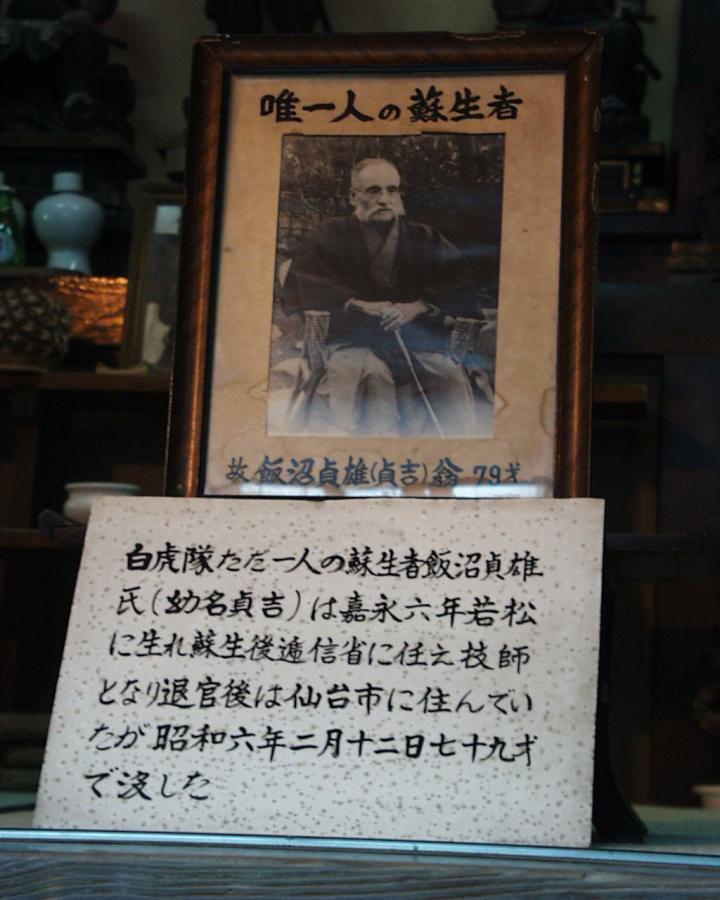

In 1993-1997 the authors of the present book visited Japan several times, including its central part and the famous Aizu Valley. The city of Aizu-Wakamatsu, which is located at the very centre of the valley, was the Samurai stronghold during the war of 1867-1868. The city has a memorial commemorating several young Samurai, all of which (with a single exception) were killed during the war. One of them, who had still been a young boy, stayed alive until the middle of the XX century. There is a photograph of this Samurai in the local museum, taken when he was already an elderly man. The person we see in the photograph is distinctly European, with sideburns and large facial features – there is nothing remotely Asian about him (see figs. 7.17 and 7.18). Next to the photograph we see a painting of the Samurai (including this character) on the battlefield, defending this very location. It was obviously painted by a contemporary Japanese artist, whose knowledge of Japanese history already came from modern textbooks and films. Therefore, all the Samurai are depicted as typical Asians. Museum visitors usually only look at this painting – few of them pay any attention to the small but authentic photograph of the Samurai.

This is how history often becomes counterfeit – often without any malicious intent. Incidentally, one still encounters Japanese with purely European features in Aizu Valley – we have witnessed this ourselves many a time. In the Aizu Museum of History one learns that, according to archaeological excavations, there were two races inhabiting the region of Aizu – European and Asian. It is quite natural that archaeologists try to date the graves of the “Japanese Europeans” to deep antiquity; however, many of them might be relatively recent and date from the first half of the XIX century, for instance.

2. Mediaeval Japan could have been a Christian country. Traces of Russia, or the Horde, in Japan.

Could the very name Aizu be derived from the name Jesus? After having seen the huge cross over the Japanese Isles on an old Portuguese map, this explanation becomes perfectly natural. This area was populated by Christians.

There is another related fact, which testifies to the above postulation rather eloquently. The northernmost large island in Japan is called Hokkaido today. What was its name in the XVII century? Let us open the abovementioned Atlas of Blau dating from 1655 and take a look at the map that depicts China and Japan, qv in fig. 7.19. We can plainly see that Isle Hokkaido was known as Ieso in that epoch – we believe the name to stand for “Jesus”.

Let us now consider another map from the same atlas of Blau (fig. 7.20). It shows the southern part of the modern Isle Hokkaido; however, the island is called Esu, which is a rather apparent modification of Jesus. Moreover, the XVII century cartographer drew a Christian cross right next to this name – obviously, to leave no doubts that the name in question is a reference to Jesus (see fig. 7.20).

Therefore, the gigantic Christian cross that we see drawn over Japan in a number of mediaeval maps, qv above, is there for a reason. Further events are easy enough to reconstruct. After the social and political changes that took place in Japan, all the Christian names, including that of Jesus, which was used for referring to the large island in the North, were replaced – for such names as “Hokkaido”, for instance, in order to purge mediaeval Christianity from Japanese history for good.

Obviously enough, modern historians are of the opinion that there have never been any Christians in these parts – solely the Buddhists. However, let us consider the photograph of the Buddhist temple banner from the “Samurai Household” Museum in Aizu-Wakamatsu, qv in fig. 7.21. We see a deity with a halo on top, and twelve figures underneath – eleven of them with halos of saints. The twelfth has no halo; moreover, the figure is depicted in an explicitly negative fashion – it has a contorted evil grimace and so on. The figures obviously represent Jesus Christ and his twelve apostles. Eleven have got halos around their heads; the twelfth is Judas, who has obviously got no halo, being the betrayer of Christ. Thus, what we see on the ancient Buddhist banner is obviously an Evangelical Christian theme, although modern Buddhists may well be unaware of this fact.

Obviously enough, modern historians are of the opinion that there have never been any Christians in these parts – solely the Buddhists. However, let us consider the photograph of the Buddhist temple banner from the “Samurai Household” Museum in Aizu-Wakamatsu, qv in fig. 7.21. We see a deity with a halo on top, and twelve figures underneath – eleven of them with halos of saints. The twelfth has no halo; moreover, the figure is depicted in an explicitly negative fashion – it has a contorted evil grimace and so on (see fig. 7.22). The figures obviously represent Jesus Christ and his twelve apostles. Eleven have got halos around their heads; the twelfth is Judas, who has obviously got no halo, being the betrayer of Christ. Thus, what we see on the ancient Buddhist banner is obviously an Evangelical Christian theme, although modern Buddhists may well be unaware of this fact.

Now let us consider the “Japanese Mythology” section of the encyclopaedia entitled Myths of the World ([533], Volume 2, page 685). Deities in Japanese mythology are called Kani – apparently, “khany”, or “Khans” ([533], Volume 2, page 685). There were three primary deities, or Khans, in Japan initially.

The first deity, or Khan, was called Ame-No Minakanushi, or MN-MN-KHAN (possibly, “Mongol Khan”).

The second was known as Takamimusubi, or T-KHANN-SUB (“T Siberian Khan”?)

The name of the third deity was Kamimusubi, or KHNN-SUB (“Siberian Khan”?)

Next we are told of the main female deity in Japan, with the beautiful name of Amaterasu – possibly, “mat russov”, or “Mother of the Russians”. She receives “the domain of the ‘high heaven’s plain’ as her own and becomes the primary deity of the pantheon” ([533], Volume 2, page 685). We see Siberian Khans and “Mother of the Russians” as the mythical figures who stand at the source of Japanese history, acting as the founders of the Japanese kingdom. This fact is explained well by our reconstruction – Japanese myths have preserved the memory of the “Mongolian conquest” of the XIV-XV century, which also reached Japan.

It is possible that the second wave of the “Mongol and Chinese” (or the Great Scythian) colonization of Japan dates from the XVI – early XVII century. According to our reconstruction, the fragmentation of the gigantic “Mongolian” Empire had already started, which made Japan, already firmly in command of the Horde, one of such fragments in the XVII century (although by no means a separatist state – it remained true to the spirit of the Horde Empire). As a result, in the early XVII century many ethnically European Cossacks from the Horde (the Oriental Dapple Horde first and foremost) joined their brethren in the faraway Japanese Isles in the Far East, fleeing from the invasion of the pro-Western Romanovs. The last representatives of the Horde, unwilling to submit to the usurpers, left the continent for good. Japanese chronicles report the arrival of a new ruler named Tokugawa Ieyasu in Japan around this time (1542-1616) – see [1167:1], page 20. It is possible that the chronicles are really describing the advent of a new wave of Christian Cossacks under the banners of Jesus Christ, or the Samurai (Samarian) Crusaders.

Incidentally, the period of 1624-1644 is officially referred to as the “Kan’ei period” in the consensual version of Japanese history ([1167:1], page 20). As we realise today, the name stands for “Khans’ period”. It is interesting that around this time Japan became completely isolated from the outside world ([1167:1]). It is likely that the Khans of the Horde, who were regnant in Japan, strived to protect their country from the “progressive reformers” of the XVII century, who had split up the Great = “Mongolian” Empire and were greedily sharing out its vast legacy in Eurasia and America.

The city of Edo had been the capital of Japan for a while. In 1657 it was almost completely destroyed in a terrible fire ([1167:1], page 27). Edo is believed to have been located on the site of the modern Tokyo. It is noteworthy that, according to the consensual version of Japanese history, the so-called “Rusui” (Russians?) played a key part in the history of Japan and its central region of the capital Edo in the epoch of the XVI-XVIII century ([1167:1], page 6). A large section of the Japanese book on the history of Edo and Tokyo is entitled “Rusui as Diplomats and their Role” ([1167:1], page 6). Japanese historians report the following: “We cannot forget the Rusui, who represented every feudal domain [of Japan – Auth.], and made a great influence on the culture of Edo and its environs as well as each of the provinces . . . The Rusui from different feudal domains collaborated with each other” ([1167:1], page 6). Although the modern Japanese historians refer to the “Rusui” with much respect, they do not elaborate on their identity. Let us voice the following simple consideration. Japanese sources have preserved the evidence that the Japanese Isles were colonised by Russia, or the Horde, in the epoch of the XIV-XVI century. As we see, the Russian origins of the Horde Cossacks were known as “Rusui” (and also as the Samurai) for a long time.

The military reign of the Samurai and their Shoguns lasted until the middle of the XIX century. According to historians, “the Chinese cultural influence on Japan was tremendous, especially in the epoch of Edo” ([1167:1], page 11). As we have noted above, under “China” (or “Kitai”) we have to understand Scythia.

It has already been pointed out that during the Samurai epoch of the XVII-XIX century the Japanese Isles were largely isolated from the outside world as a means of protection from the Western mutineers. However, the divide of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire’s legacy in Eurasia and America finished around the middle of the XIX century, and the reformers turned their attention towards the remote Japanese Isles, which had formerly been the last bastion of the old imperial Samurai spirit. Japan was to come next.

In the middle of the XIX century the European warships (evasively referred to as “trade vessels” in some of the modern history textbooks appeared at the coast of Japan. Europeans had organised a military coup that resulted in the fall of the Samurai reign. This period was later slyly named “Meiji Restoration” – presumably, a comeback of the former values, political structures and ideals ([1167:1], page 104). In reality, the process in question wasn’t a restoration of any kind, but rather the conquest of the Samurai Japan by the European reformers. The last stronghold of the Samurai, or the camp of the Shogun in the city of Aizu-Wakamatsu in the North, was conquered and destroyed.

Modern Japanese historians are usually rather close-lipped about this turbulent and rather dark epoch in Japanese history. This is how it is related in [1167:1]. The relevant section bears a rather suggestive title – namely, “The Arrival of the ‘Black Ships’”.

“In 1853 Commodore Perry brought a host of warships into the haven of Edo, carrying the missive of Fillmore, the US President, addressing the bakufu with a demand to make Japan open to the outside world. Perry came back the next year insisting that Japan be made open in straightforward terms . . . The two hundred years of isolationist policy came to an end . . . The clans from the regions of Satsuma . . . and Choshu took advantage of the political situation. These political fractions had first attempted to banish the foreigners in order to form a state based on the power of the emperor. However, after a skirmish with the English troops they became aware of the Westerners’ military supremacy, and renounced their former policy of hostility towards Europe and the United States. Instead, the anti-bakufu coalition turned its attention towards the military government [the Samurai government of Japan – Auth.]. In 1868 the troops of the anti-bakufu coalition entered the Citadel of Edo without meeting any resistance” ([1167:1], page 103).

This is how the epoch of the Horde and the Samurai ended in Japan. In the second half of the XIX century the wave of “Reformation” swept over the conquered country, bringing Japanese life in line with the Western and American standards ([1167:1]), page 104.

One must add that a while later the Japanese became nostalgic for the epoch of the Samurai, or the XVI-XIX century: “It is with the greatest nostalgia that we think of the epoch of Edo” ([1167:10], page 10). The Japanese still admire the mediaeval Samurai, and respect them greatly.

3. The manufacture of the famous Samurai swords involved the “Tartar Process” in the Middle Ages.

Now let us turn to the history of arms blanches in Japan. The following fact was made known to us by S. N. Popov, the USSR Graeco-Roman Wrestling Champion and the Double Absolute Karate Champion of Russia. Apparently, “Magnum. The New Weapon Magazine” published an article of L. Arkhangelskiy in 1998 entitled “Samurai Steel”. The article analyses the history of the famous Samurai swords ([37]). The very beginning of the article catches one’s attention instantly: “The famous . . . swords of the Samurai aren’t actual swords, strictly speaking, but rather typical sabres, which is the very name that was used for the single-bladed side arms of the Samurai in Russian literature before the revolution” ([37], page 18). Let us remind the reader that the Horde Cossacks were armed with sabres.

“There are 117 catalogued swords that classify as ‘extremely valuable’, and about three thousand more that fall under the ‘valuable’ classification . . . The main distinctive characteristic of the Samurai swords . . . is the metal of the blades and the methods used for forging it” ([37], page 21). Further on, the author describes a special technique used for the manufacture of steel for Samurai swords, reporting the following curious fact: “The bar of bloomery steel known as oroshigane was hammered into a sheet and quenched in water . . .” ([37], page 21). L. Arkhangelskiy proceeds with the discussion of technical details concerning the manufacture of the Samurai steel.

The word “oroshigane” from the quoted fragment deserves our special attention – it is possibly a derivative of “Rosh-Khan”, or “Russian Khan”. It is likely that the steel used for Samurai swords in mediaeval Japan was known as “the steel of the Russian Khans”, the reason being that the method of its manufacture was brought to Japan by the conquerors from Russia, or the Horde.

An echo of the Russian (Horde) origins of the mediaeval Samurai weapons has also survived in another name. According to L. Arkhangelskiy, “iron sand was also refined with another method, known as the Tatara Process” ([37], page 21). Tartar process, in other words. “This method came to Japan from Manchuria many centuries ago – possibly, as early as in the VII century, and became particularly popular in the Muromashi epoch (1392-1572). The last “Tatara furnace” stopped functioning as recently as in 1925” ([37], page 21).

Thus, according to the expert opinion on the metallurgy of Samurai steel, the “Tartar method” of its manufacture was particularly widespread in the XIV-XVI century, which is the very epoch of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire. Our reconstruction explains this fact perfectly well.