Part 3.

Scythia and the Great Migration. The colonization of Europe, Africa and Asia by Russia, or the Horde, in the XIV century.

Chapter 8.

West Europeans writing about the Great = "Mongolian" Russia.

4. Mediaeval Western reports about the Kingdom of Presbyter Johannes, or the Russian Empire (the Horde) in the XIV-XVI century.

4.1. The “antiquity” and the Middle Ages are fused together on geographical maps.

We shall proceed to tell the reader about a number of important mediaeval documents. In particular, we shall use the fundamental oeuvre of J. K. Wright, the famed specialist in the history of geography, entitled Geographical Conceptions in the Crusade Epoch ([722]). Wright collected a large body of materials about the geographical concepts of the Europeans in the alleged XII-XIV century.

He instantly reports that all the researchers of mediaeval maps and geographical descriptions are amazed by the “proximity between Biblical characters, the ancient and the modern kingdoms [sic! – Auth.]. History becomes recorded in cartography, likewise ecclesiastical iconography, where the characters of the Old and the New Testament are depicted alongside the sages and the rulers of the later epochs” ([722], page 10).

Our reconstruction explains this fact well enough. Mediaeval authors and cartographers gave veracious accounts of their epoch (the XIII-XVI century), which had also comprised the events described in the Bible and those of the so-called “antiquity”. Hence their fusion in mediaeval geography.

4.2. The “Mongol” (Russian) Horde of the XIV-XVI century described in the Bible and the Koran as the famous nations of Gog and Magog.

As we shall demonstrate in CHRON6, many parts of the Bible were written in the XV-XVI century – much later than the Great = “Mongolian” Conquest. It is little wonder, then, that the “Mongolian” conquest became reflected in the Bible; some of the books of the Biblical canon relate it from the viewpoint of the Westerners.

This is what the mediaeval residents of the Western Europe wrote about the XIII-XVI century “Mongols” in the XVI-XVIII century. These accounts later became backdated by 300-400 years in Scaligerian chronology.

According to J. K. Wright, “Asia was often referred to as the location of the paradise and as the place where man was created. Mediaeval tradition also located the nations of Gog and Magog here, whose advent on Judgement Day would herald the death of the whole world. We find three descriptions of Gog and Magog in the Bible. Taking into account the Book of Genesis (X, 2), where Magog is named son of Japheth, Hebraic tradition regarded this obscure and foreboding character as the patriarch of the Scythian tribes.

The Book of Ezekiel the Prophet (XXXVIII-XXXIX) contains the prophecy of great destructions and havoc to be caused by Gog from the land of Magog [the land of the Mongols – Auth.], Great Prince of Meshech [Moscovia – Auth.] and Thubal [or Tobol in Siberia – Auth.], who will come from the North with his monstrous Hordes and bring death and desolation to the land of Israel” ([722], page 74).

Since, as we have already mentioned, Gog, Magog, Meshech and Thubal appear to identify as the nations of the XI-XVI century A. D., we encounter a confirmation of the statistical results related in CHRON1 and CHRON2, namely, that the Biblical books of the Old and the New Testament (the Apocalypse in particular) were written in the epoch of the XI-XII century A. D. the earliest.

Thus, the ancient chronicles have informed us that the Biblical Gog and Magog can be identified as the Scythians, or the Goths. As we realise nowadays, the events described in said chronicles date from the XIV-XVI century. St. Jerome, for instance, refers to some oeuvre wherein Gog and Magog are directly identified as the Goths ([722], page 74). Nothing surprising – we already know of this identification from other sources, qv in CHRON4.

J. K. Wright adds: “The apocalyptic legend of Gog and Magog became as widespread in the Orient as it was in the Christian world. Oddly enough, it became part of the ‘Tale of Alexander’ in the East. The Koran tells us that ‘Alexander the Bicorn’ erected a tall wall of bronze, tar and sulphur, to lock away the wild tribes of Yajuj and Majuj (Gog and Magog) until they break free on Judgement Day. Procopius must have been the first to tell this legend in association with the name of Alexander the Great (in his tractate ‘On the Persian War’)” ([722], page 74).

The same considerations as voiced above lead us to the hypothesis that the creation of the Koran and the lifetimes of Alexander the Great and Procopius should also be dated to the epoch of the XI-XII century the earliest.

As for the actual word “Gog”, it has to be pointed out that one of the versions of the name George still widely used in the Caucasus is “Gogi”. Bear in mind that, according to our reconstruction, the Great = “Mongolian” Empire was founded by Great Prince Georgiy Danilovich (also known as Genghis-Khan).

4.3. The war between the Russian “Mongol and Tartar” Horde and the “ancient” Alexander the Great.

4.3.1. The wars against Gog and Magog and the gigantic wall that held them “in seclusion”.

Let us cite some interesting data collected by J. K. Wright in a special paragraph entitled “Gog and Magog”. He writes the following in wake of his analysis of the ancient chronicles: “It was presumed that the northern part of Asia had been inhabited by the terrifying tribes of Gog and Magog, whose arrival at Judgement Day would be the death of all humanity. We have seen that the Biblical prophecies were woven together with the legend of Alexander the Great, who had built tall walls around these tribes.

Different versions of this legend existed in the epoch of the Crusades. Most maps depicted Gog and Magog behind a wall [possibly, a symbolic representation of the “iron curtain” between the Western Europe and the Horde, or Russia? – Auth.]; some of them sport derisive epithets, such as ‘filthy nation’ (gens immunda). In the map of Palestine by Matthew of Paris the walls built around Gog and Magog by Alexander the Great are depicted in the North; the explanatory legend tells us that the Tartars hail from the very same parts” ([722], pages 256-257).

In fig. 8.1 we reproduce a fragment of the famous Psalter World Map from a manuscript dated to the alleged XIII century A. D., with the Wall of Gog and Magog visible in the top left corner (see fig. 8.2). This ancient representation of the Wall of Gog and Magog is also discussed in [1177] (page 333).

Time and again we see Gog and Magog associated with the Tartars and the Mongols by mediaeval Europeans. Therefore, the following important identifications, which modern historians write off as tall tales told by mediaeval chroniclers in their presumed ignorance and unfamiliarity with the authorised version of history, are obvious and natural in our conception. Namely, Gog and Magog = the Scythians = the Mongols and the Tartars = the Goths of the XIV-XVI century.

Wright tells us further: “The tractate entitled ‘On the Image of the World” simply states that the tribes locked away behind a wall by Alexander the Great ages ago live between the Caspian Mountains and the sea of the same name; they are Gog and Magog, unrivalled in cruelty and feeding on raw meat of wild beasts and humans [this appears to be nothing but Western European educational propaganda of the XVII-XVIII century – Auth.].

Muslims located Gog and Magog at the very Northeast of Asia [at some point in time that postdates the XV-XVI century A. D., that is – Auth.]: in the translation of Al-Farghani’s ‘Astronomy’ made by John of Seville, the Land of Gog is located in the furthest Eastern reaches of the sixth and the seventh climate (the Northernmost).

Lambert le Tort mentions Gog and Magog as vassals of Porre: after his victory over Porre, Alexander chased them into ravines in the mountains and built a huge wall to keep them cloistered, although their numbers equalled some four hundred thousand . . . We learn the reasons why the empire of Alexander was divided after his death: Antigonus inherited Syria and Persia, all the way to Mount Tus. He was also charged with guarding Gog and Magog. These tribes are also mentioned by Otto von Freisingen . . . According to Otto, in the times of Heraclius, the “Agarians” (Saracens) laid the empire waste, destroying a part of his army. As an act of revenge, Heraclius opened the Caspian Gates, setting free the very tribes of abhorrent savages that were blockaded by Alexander the Great near the Caspian Sea and declaring war on the Saracens” ([722], page 257).

The events in question are most likely to identify as the “Mongol and Tartar invasion”, and therefore date from the XIII-XIV century. Therefore, all these constrained Western European accounts of the “hideous tribes of Gog and Magog” invariably postdate this epoch. The texts that we quote should thus be dated to the XVII or even the XVIII century, although modern historians backdate them by several centuries.

4.3.2. The wall of Gog and Magog: the time and place of its construction.

Let us try and analyse the legends of the enormous wall allegedly built by Alexander the Great to shut off Gog and Magog. First of all, let us point out that some of these allegedly “ancient” accounts of Alexander the Great and Gog and Magog appear to have been written in the Western Europe around the XVI-XVII century. In CHRON1 A. T. Fomenko demonstrates that among the real events that later legends of Alexander the Great were based upon we find the Ottoman (or simply Ataman) conquests of the XV-XVI century in particular. The father of Alexander, or the famous “ancient” Philip II is most likely to be identified as Sultan Mohammed II, whose lifetime dates to the XV century A. D. – possibly, a Slav (a Macedonian?).

However, when the above events were dated to the XVII-XVIII century by later chronologists, whether deliberately or accidentally, Alexander of Macedon became the protagonist of the entire epoch. His original, or originals, must have lived in the XV-XVI century. We cannot provide them with any finite identification. Most likely, Alexander of Macedon was an Ottoman (Ataman?), qv in Part 5; however, he became credited for nearly every substantial accomplishment of that epoch, including the construction of the Great Wall as a line of defence against his own kin (the Ottomans/Atamans/Cossacks, also known as Gog and Magog.

Now let us see whether there was any Great Wall constructed in the XV century Europe to hold back the onslaught of the Ottomans, or Atamans, later to be known as the Turks.

Indeed, there was such a wall – built in Greece, right in the XV century. It was known as Hexamilion, and it spanned the entire Isthmia, isolating Peloponnesus from the mainland ([195], page 306-307). It was built in 1415 by Manuel, Emperor of Byzantium, who is known to have been on good terms with the Ottomans – their military ally, in fact ([195], page 306). The compilers of later chronicles must have become confused as a result.

This is how it happened. “Having secured a peace with the Sultan, the Greek Emperor [Manuel – Auth.] . . . was also extraordinarily keen about the construction of the Hexamilion, or a wall across the Isthmia, initially assisted by the Venetians. The Greeks fancied this obstacle to make Peloponnesus impenetrable for the enemy. It took thousands of workers to erect this Gargantuan structure . . . An enormous wall with moats, two fortresses and 153 fortified towers grew between the two seas . . . All of Manuel’s contemporaries had been in awe of this construction – a cousin of the famed mounds of Hadrian; however, they soon found out that it was far from impenetrable for the janissaries” ([195], pages 306-307).

Later commentators from the West of Europe were positively infatuated with this construction built by Manuel. Gemisto Pleton and Masaris considered the wall “a magnificent construction and an unconquerable citadel. Franza also wrote an epistle to Manuel in re this Isthmian Wall” ([195], page 307).

However, several years later, in 1423, the Ottoman = Ataman army broke through this formidable line of defence, with the fierce janissaries in the avant-garde, as usual. This is how the terrifying apocalyptic nations of Gog and Magog “broke free, numerous as the sand on the seashore”. It happened in the following manner: “In May 1423 he [Sultan Murad II – Auth.] sent Turakhan-Pasha [the Turkish Khan – Auth.] forth from Thessaly as the leader of a great army to drive Theodore II and the Venetians away from their domain in Morea . . . The great construction of Manuel, or the Isthmian Wall, was taken by storm and then destroyed by the janissaries” ([195], page 311).

But why would mediaeval authors locate the “great wall built to hold back Gog and Magog” in the vicinity of the Caucasus, or upon the shores of the Caspian Sea? Our reconstruction provides an adequate answer. Since the Ottoman (or Ataman) Empire and Russia (or the Horde) had still been parts of the united “Mongolian” Empire, the “land of Gog and Magog” obviously lay to the North of the Caspian Sea, identifying as Russia. Therefore, the compilers of the XVII-XVIII century chroniclers, confused by the geographical information contained in the surviving old texts and striving to establish the real location of the wall built as a protective measure against the terrifying Gog and Magog, naturally chose the shores of the Caspian Sea as the most likely option – one of the most famous routes used by the invaders from the Horde, or ancient Russia, in the days of yore, as their armies rode to the West and the South. It suffices to recollect the internecine wars between the Golden Horde and the Persian ulus of the “Mongolian” Empire, or Persia.

Finally, let us remark that there weren’t more than two Great Walls in the history of Europe:

1) The famous “Wall of Gog and Magog” can probably be identified as the Isthmian Wall. Let us emphasise that this single truly great wall was built in Europe in the XV century, which is the very lifetime of the primary historical original of Alexander the Great, or the presumed builder of the wall.

2) Alternatively, the Wall of Gog and Magog can be identified as the famous triple belt of walls around Constantinople, or Istanbul. We are referring to the so-called Wall of Theodosius ([1464]), which was erected in the beginning of the alleged V century A. D. It is ascribed to Theodosius, Emperor of Romea ([1464], page 78). The assumption is that the construction of the Wall of Constantinople was only finished in the XII century A. D., when Emperor Manuel II built the last part of the wall adjacent to the Golden Horn bay. In reality, it must have happened much later.

The Wall of Constantinople really makes a strong impression. Its total length equalled some 20 kilometres. The wall surrounded Constantinople, protecting it against assaults from the coast and the sea. The part of the wall that ran along the coastline was constructed as follows (see fig. 8.3 and [1464]):

- On the outside there was a moat, 18 metres wide and 7 metres deep.

- After the moat came the first line of walls, which weren’t particularly tall.

- Next came the second line of walls, 8 metres tall and 2 metres thick.

- Finally, there was the third line of walls, 13 metres tall and 3-4 metres thick.

- The second and the third line of walls were fitted out with 96 watchtowers each.

- From the side of the Marmara Sea Constantinople was protected by a single line of walls, about 12-15 metres tall. There were 150 towers and 8 gates here.

- From the side of the Golden Horn Bay there was another line of walls, 10 metres tall, 100 towers and 14 gates.

The wall of Constantinople was made of hewn stone, with layers of red brick. Large fragments of the wall have survived until the present day, and they give one a good idea of how it had looked in the past (see figs. 8.4, 8.5 and 8.6).

It becomes clear that Gog and Magog could be regarded as cloistered behind this wall of Istanbul, in a way; the first time, when the Ottomans (Atamans) and the Russians from the Horde were storming New Rome, and the second, in the XV-XVI century, when Constantinople was already conquered by the Ottomans and the Horde of the “Mongols”, or the very same Gog and Magog, since, as we shall explain later on, the Ottomans also originated from the Great Russia, or the Horde.

History contains some information about the legendary “ramparts of Hadrian”, presumably built by Hadrian, the Roman emperor – it is possible that these ramparts are but a reflection of the very same wall around Constantinople. Incidentally, in the XV century A. D. the name of Hadrian “reappears” as the name of the Turkish capital, or Adrianopolis – “Hadrian’s city”, that is ([797], page 1526). It is presumed that this city was the capital of Turkey before 1453. Could it have been another name of Constantinople initially, later to migrate westwards and become affixed to the city known as Edirna nowadays? The name “Hadrian” is very likely to have the same root as the word “horde” (as well as the word “guard”, as matter of fact). In this case, the ramparts of Hadrian were the ramparts of the Horde.

The Russian word for “rampart” is “val” – it strongly resembles the English word “wall”. Another rampart built by Hadrian has survived in Britain, qv in CHRON7.

4.4. The “Mongolian” conquest as described by later Western European chroniclers.

After the decline of the “Mongolian” Empire in the early XVII century, the Great = “Mongolian” conquest became demonised to the greatest extent, in Western Europe as well as Romanovian Russia, without any particular qualms about the choice of words.

Let us cite some vivid fragments of European chronicles dated to the alleged XIII-XIV century and most likely written or heavily edited in the XVII-XVIII. They describe the invasion of the “Mongols” as the invasion of the barbarians Gog and Magog.

The “Great Chronicle” by Matthew of Paris describes the Tartars in great detail (the section that reports the events of the alleged year 1240). This is what he tells us (bear in mind that the real dating more likely pertains to the epoch of the XVI-XVII century):

“And so it came to pass that the joys of the mortals were not to be permanent, and their state of peace and comfort would not last, for that year an accursed satanic tribe suddenly appeared from beyond the mountains. Having torn through the monolithic wall of solid rock, like demons breaking free from Tartarus (which is why they were called Tartars), they swarmed across the whole of the land like locusts” ([722], page 240).

Matthew’s reference to the “monolithic wall of solid rock” clearly identifies the Tartars as Gog and Magog coming from beyond the “Wall of Alexander”.

Matthew tells us further: “The borderlands of the East were laid waste and desolate with fire and swords . . . They are an inhumane folk, more like wild beasts of prey, and should be called monsters rather than people, for they thirstily drink blood; they tear apart canine and human flesh to devour it” ([722], page 240).

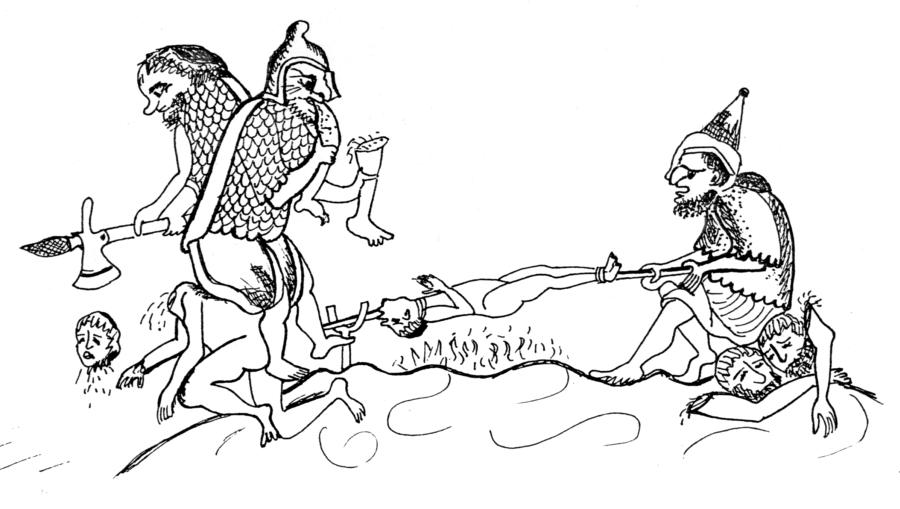

As we have mentioned in CHRON4, Chapter 18:17, Matthew of Paris complements the above passage with a very picturesque illustration (our drawn copy thereof can be seen in fig. 8.7). See [1268], page 14. On the left we see a “Mongol barbarian” decapitating his unfortunate victim, while another Mongol holds severed human legs in both hands, ecstatically drinking the blood that pours out, and a third is drooling in anticipation of tasty meal as he calmly roasts a human carcass on a spit.

This is how the Western Europeans depicted the ancestors of the modern Slavs in the XVI-XVII century or later. One gets the feeling that in the XVII-XVIII century a certain schism between the nascent Western European and the oriental “Mongolian” Russian mentality and Weltanschauung occurred; even today, there is a certain difference between the two.

Let us revert to Matthew of Paris. He tells us the following about the “Mongols”: “They dress in bovine skins, and cover themselves with metal plates” ([722], page 240). We doubt it that the metal plates could be forged in the wilderness of the steppes; therefore, the “Mongols and Tartars” must have known metallurgy and had a well-developed armaments industry.

Further also: “They are short and sturdy, and their strength is unsurpassable. They are invincible in wars and tire not in battle. They wear no armour on their back, only protecting their front side . . . Human laws mean nothing to them; they know no mercy, and are fiercer than lions and bears. They practise communal ownership of vessels made of calfskin – every ship has about a dozen owners. Apart from being good swimmers, they can navigate their ships very well, and cross even the widest and fastest rivers swiftly and with ease.

When they cannot get any blood, they eagerly drink turbid and even muddy water . . . [customarily quenching their thirst with nothing but fresh blood, one must assume – Auth.]. None of them speaks any other language but their own, which isn’t known to any other nation, since they had formerly lived in seclusion, without coming out of their dwelling place and letting no strangers in . . . They take their herds with them, as well as their wives, which are taught the art of war just like the men . . .”

Further on, Matthew elatedly descants as follows: “It is believed that these Tartars, who are repulsive even to mention, are the descendants of the ten tribes that rejected the law of Moses and followed the golden calves – the ones that Alexander the Great had initially tried to shut away with tar stones behind the Caspian mountains. When he realised that this task exceeded the powers of humans, he called upon the God of Israel for help, and the mountaintops locked together, forming an impenetrable obstacle . . .

However, ‘Scientific History’ tells us that they shall break free when the end of the world is nigh, to instil terror in the hearts of mankind. One wonders whether they could be the Tartars, for they speak no European language, know not the Law of Moses, and have no legal institutes” ([722], pages 240-241).

By the way, it is believed that the capital of the “Mongolian” Empire, or the city of Karakorum, was in Siberia, near Lake Baikal ([722], page 241). All the searches have been fruitless so far, strangely enough, although mediaeval authors report that it was a big city. Could it have vanished without a trace?

On the other hand, the famous city of Semikarakorsk still exists in the Don region, as we pointed out in CHRON4. Shouldn’t we stop the fruitless search of Karakorum in the desolate environs of Lake Baikal?

5. The Kingdom of Presbyter Johannes, or the Russian and Ataman Horde as the dominant power of the XIV-XVI century.

5.1. Presbyter Johannes as the liege of the Western rulers.

According to J. K. Wright, “this legend was a romantic tale of a great and powerful Christian kingdom in these remote parts, ruled by a mighty monarch known as Presbyter Johannes . . . Despite all of its fallacy [as the traditionalist Wright assures us – Auth.], this belief existed for a long time and became an integral part of the geographical theory in the late Middle Ages, having affected the course of research for many years to follow” ([722], page 253).

Many mediaeval legends about the Kingdom of Presbyter Johannes emphasise its amazing wealth and indubitable political supremacy over the rulers of the West. For example, let us cite an Italian novel dated to the XIII century nowadays. This book was “very popular in the XIV-XV century, hence the large number of surviving manuscripts” ([587], page 253).

The book begins with an account of how Presbyter Johannes sent envoys to the Western Emperor Frederick. Johannes made Frederick a present of a stone that cost more than the entire empire of Frederick and offered him the position of a seneschal at his court. The story makes it obvious that Frederick wasn’t insulted by the offer the least bit – on the contrary, he was very pleased ([587], pages 6-8).

It would be interesting to compare this mediaeval account to the reports of Frederick II being a correspondent of Batu-Khan. We are told that Emperor Frederick II was the only one to keep calm amidst the panic that spread over the entire Western Europe when the Mongols invaded ([211], page 512).

The reader might think that Emperor Frederick was mighty and brave, so Batu-Khan did not frighten him. However, the situation was different. We learn of the following. “Batu-Khan . . . demanded obedience from Frederick . . . Frederick replied . . . that, being a connoisseur of falconry, he could become the Khan’s falconer . . . This resulted in . . . the isolation . . . of Hungary, its defeat and the victories of Frederick II in Lombardy” ([211], page 512).

In this quotation the dots replace the attempts of L. N. Gumilev to “explain” this situation, which certainly looks strange to a modern historian – Emperor Frederick offering his services in the capacity of a falconer. Having thus secured Batu-Khan’s favour (and, possibly, actually received the title of a falconer from Batu-Khan) Frederick defeats his neighbours, successfully and in full poise.

A propos, the falconer’s title did not imply the necessity to be physically present at the Khan’s court. It was a common mediaeval title that gave its bearer certain benefits – such as the right to crush one’s neighbours, which didn’t manage to receive an equal title from Batu-Khan. Gumilev shouldn’t have attempted to present the whole situation with Frederick as a joke – most probably, the panic that had gripped the entire Europe in that epoch didn’t strike Frederick as a fitting atmosphere for joking.

We believe that the correspondence between Frederick and Presbyter Johannes is the exact same thing as the correspondence between Frederick and Batu-Khan. Let us remind the reader that, according to our reconstruction, Presbyter Johannes and Batu-Khan were the same historical personality, namely, Great Prince Ivan Kalita (Caliph). The difference between the two versions of the legend is marginal – Presbyter Johannes offered Frederick the position of a seneschal, whereas in the version with Batu-Khan Frederick was to become a falconer. It could be that the mediaeval editor encountered the unfamiliar Russian word “sokolnichiy” (“falconer”) in the text of a chronicle and replaced it with a more common and understandable title of seneschal.

However, such reports shouldn’t surprise us. Above we cite an identical report of Matthew of Paris about the epistle sent to the French king by the Khan of the Tartars and the “Mongols”, which expresses the same idea, namely, that the Great (“Mongolian”) Khan considered it perfectly natural that the French King should be his vessel, whereas the latter was also taking this circumstance for granted.

There was another missive sent by Presbyter Johannes to Manuel, Emperor of Byzantium. It is believed that it was written in Arabic – however, the original did not survive, and all we have at our disposal today is the Latin translation ([212], page 83).

The beginning of the letter is very interesting indeed: “Presbyter Johannes, King of Kings and Lord of Lords by the mercy of our Saviour Jesus Christ wishes good health and prosperity to his friend Manuel, Prince of Constantinople” ([212], page 83).

The arrogant manner in which the “mythical” Presbyter Johannes addresses a mighty Byzantine Emperor cannot fail to raise an eyebrow of the modern historian. L. N. Gumilev writes the following in this respect: “This manner of addressing alone could make the reader with the slightest predisposition towards criticism somewhat suspicious at the very least. Johannes calls his vassals Czars, whereas Manuel Comnene, a sovereign ruler, is addressed as ‘Prince of Constantinople’. Such blatant disrespect for no apparent reason should have led to a cessation of diplomatic relations and not a friendly union. However . . . in the Catholic West it was accepted as perfectly natural, without invoking any suspicions concerning the text, which would be quite in order [as L. N. Gumilev disappointedly tells us – Auth.]” ([212], page 83).

How are we supposed to interpret all of the above? Let us enquire of whether such “impolite” missives sent by one monarch to another are known in the history of XVI-XIX century diplomacy. They were written by Muscovite rulers of the XVI century (Ivan the “Terrible”), for instance. Let us consider his letter to Elisabeth I, Queen of England, whose original has survived until today ([639], page 587). It is believed that the letter is still kept in London archives ([639], page 587).

This is what the modern commentators have to say about this letter. “Likewise many other letters, it combines certain diplomatic characteristics with the offensive style of Ivan IV” ([639], page 586). First of all, Czar Ivan uses “we” for referring to himself, whereas the English queen is addressed as “ty”, which is the informal Russian form of “you” – the whole tone can thus be seen as condescending. Also, the style of the letter is respectful on the whole (the English queen is thus an exception in the eyes of Ivan IV, since he considers her a born royalty as opposed to the Swedish king, for instance, qv below) – however, he addresses her patronisingly. At the end of the letter he gets angry and even calls the queen a “wanton maiden” ([639], page 114).

The letters sent by Ivan the “Terrible” to the Swedish king are an even better example. Ivan writes: “You are of peasant descent, not royal . . . Tell me, whose son was Gustav, your father, and what was the name of your grandfather? What was his domain? What rulers was he related to? Are you really a king by birthright? . . . As for the Swedish kings that have ruled Sweden for hundreds of years, which you mention in your letter – we have heard nothing of them, with the exception of Magnus, who was at Oreshek – but even he was a prince and not a king” ([639], page 130).

Further on Ivan writes the following (the Russian translation is given in accordance with [639]): “The Great Rulers of All Russia have never communed with the Swedish rulers directly. The Swedes were in contact with Novgorod . . . Your father was exchanging letters with the Novgorod vicegerents . . . so when the Novgorod vicegerents send their envoy to King Gustav, he, King of the Swedes and the Goths, will have to . . . kiss the cross before this envoy . . . It shall never come to pass that you might commune with us directly – only through the vicegerents” ([639], pages 129, 131 and 136).

We see a clear indication that the rank of the Swedish king allows him direct contacts with the vicegerents of the Russian Czar, and not the Czar himself.

Further on, Czar Ivan says: “As for King Magnus . . . even he doesn’t know as much as we do about your peasant lineage – we know it from our numerous domains. As for the city of Polchev that we gave to King Arcimagnus, it was our right to give any part of our domain as a present to anyone we please” ([639], page 136).

Czar Ivan writes the following in reference to some passage about a “Roman seal” contained in some letter of the Swedish king, who must have already adhered to the newborn Scaligerian version of history: “As for the seal of the Roman kingdom that you write about, we also have a seal of our very own inherited from our forefathers; the Roman seal isn’t alien to us, either, since we trace our family tree all the way back to Augustus Caesar” ([639], page 136).

It can be suggested that Czar Ivan Vassilyevich was ill-mannered, but the omnipotent Western rulers were aware of this and tolerated his antics, believing it unnecessary to pay attention to the bad manners of some minor foreign ruler. However, this suggestion is untrue.

Let us cite a document that clearly demonstrates how the Western rulers deferred to the Russian Czar back in those days when they addressed him – with awe and full recognition of his superiority. On 27 February 2002 we visited the exposition called “Revived Documental Treasures of the Archive of Ancient Acts” (8 February – 1 March 2002) in the exhibition hall of the Archive (Moscow, Russia). Our attention was caught by an ancient parchment sized approximately 50 x 70 cm. The information sign next to it read as follows: “The ratification of the treaty between Russia and Denmark by Frederick II, King of Denmark. 3 December 1562. Parchment. Received in Copenhagen by the Russian envoys, Prince A. M. Romodanovskiy-Ryapolovskiy and I. M. Viskovatiy”.

Let us read deeper into the text of the document, wherein the Danish king addresses the Russian Czar. It is quite remarkable that the document was written by the Danes in Russian.

“By the will of the Lord and by the love between us, you, Czar and Great Prince of All Russia by leave of the Lord, the Great Ruler of Vladimir, Moscow and Novgorod, Czar of Kazan and Astrakhan, Ruler of Pskov and Great Prince of Smolensk, Tver, Yougoria, Perm, Vyatka, Bulgaria and other lands, Lord and Great Prince of Novagorod, the Lower Lands, Chernigov, Ryazan, Volotsk, Rzhev, Belsk, Rostov, Yaroslavl, Byeloozero, Ugra, Obdoria, Kondinsk, Siberia and the Northern Lands, Lord and Ruler of Livonia and other lands, have made me, Frederick the Second, Ruler of Denmark, Norway, Wendia and Gothia, Prince of Schleswig, Holstein and Litmar, Count of Woldenbor and Denmalgor etc, in good will, neighbourhood and unity, for which end the envoys are sent to you, Great Ruler Ivan, Czar and Prince of All Russia by leave of the Lord . . .”

The document ends as follows:

“We, Frederick the Second, King of Denmark and Norway, Wendia, Gothia, Prince of Schleswig, Holstein, Sturmann and Diemar, Count of Woldenbor and Denmalgor, and other lands, swear to maintain eternal peace between our lands as per this pact. Written in Kapnagava, on 3 December 7771 [the remnant is lost – Auth.]”.

There are many interesting details here. The most noteworthy fact is that Frederick, King of Denmark, openly states that the Russian Czar Ivan Vassilyevich made him King of Denmark. We can therefore see the true political climate of the XVI century emerge from this text – it is strikingly different from how Scaligerite historians present it. Apparently, the Russian Czars, or Khans, appointed kings to the Western thrones as their vicegerents. The Danish throne was among the most important ones in the Western Europe. In particular, the power of the Danish king would spread as far as Britain at times, qv in CHRON4, Chapter 16:3.2.

We are beginning to understand why the titles of the Danish king add up to a much shorter list in his missive than the titles of the Russian Czar that he lists in the very same document. The titles of provincial vicegerents were naturally nowhere near as magnificent as the titles of the Emperor of Russia, or the Horde, ruler of the whole Empire. It also becomes clear why the Danish king doesn’t begin his letter with a formula like “We, King of Denmark, address . . .”, but, rather, the much more loyal “By the will of the Lord and by the love between us”, listing all the titles of Ivan Vassilyevich before he proceeds with his own.

Furthermore, as we already mentioned, it is curious that a missive sent by a Danish king should be written in Russian. Apparently, Russian was considered the official language of the Empire, not just in Russia, but also the Western European provinces. According to the actual document, it was written in Copenhagen and given to the Russian envoys so that they might take it to Russia. However, even if what we see is a Russian translation of a Danish original, it doesn’t affect the matter substantially.

The name “Kapnagava”, obviously an old version of the more Romanised “Copenhagen”, sounds distinctly Slavic.

It has to be said that we were fortunate to come across this ancient document. We have enquired with a staff member of the Archive who was in the exhibition hall and found out that the original of the pact signed between Ivan the Terrible and Frederick II wasn’t published in our epoch. This is perfectly understandable – the inferior position of the Western rulers in relation to the Great Czar, or Khan, of Russia, or the Horde, is too visible. It appears that Scaligerian history conceals these scarce authentic pieces of evidence that have survived. The fact that they were exhibited publicly in 2002 must be a chance occurrence – it is quite possible that the mute archives still conceal more relics of the Empire’s real past dating from the XIV-XVI century.

5.2. The foundation of the “Mongolian” Empire and the divide of its Eurasian part three hundred years later into Russia, Turkey and the Western Europe.

Our idea is as follows. All such documents as cited above reflect the real political situation in the XIV century Europe, when some part of the Western rulers was put to rout by the “Mongols” (the Great Ones). The rest were forced to recognize the authority of the “Mongol” Khan.

This hypothesis gives us the opportunity to provide a natural explanation to the “sudden cessation” of the Great = “Mongolian” invasion into the Western Europe. The most common hypothesis is that the “Mongols” became exhausted by the constant warfare, and got stuck in Russia, which had allegedly played the part of a live shield, covering the Western Europe and suffering many centuries of slavery under the yoke of the cruel invaders.

Our opinion is that the end of the XIV century conquest came when the “Mongols” had no more lands to conquer in Europe. The remaining Western European nations were forced to recognize the Great = “Mongolian” Khan as their liege. The conquerors have reached their goal.

Historians are surprised: "EIGHT MILLION inhabitants of Eastern Europe obeyed four thousand Tatars. The princes go to Saray ... to return with slanted eyes wives, pray in churches for Khan ... skillful masters go to the Karakoram and work there for a high fee "[211], p.543. There is nothing to be surprised here. After the creation in the XIV century of the Great = "Mongolian" Empire, everyone valued the great honor of being at least once in life admitted to the khan's court. Moreover, one hoped to come back from the Horde with a wife. When any talented master was politely requested to go to the metropolis, it must be assumed nobody played with a peculiar idea to dodge the invitation.

Now let us consider the following circumstance, which is very significant. The actual propagation of the political influence of the Great = “Mongolian” Horde, or Russia, throughout the lands of the Western Europe and further during the “Mongolian” conquest of the XIV century fails to find a reflection in the modern version of mediaeval European history, although, as we can see, there are more than enough relics that clearly testify to this. They are usually paid no attention and, possibly, hushed up. It is easy to understand why.

Let us remind the readers that in the XVII century the Western Europe and Russia, or the Horde, already became estranged due to the religious schism, which had started in the XV-XVI century. Therefore, the memory of the former political dependency of the Western Europeans on the “heretical” East, or the “Mongolian” (Great) Horde, was naturally extremely undesirable and uncomfortable psychologically. Moreover, one would invariably become confronted with the question of how this dependency had ended.

Although the Occidental historians haven’t managed to erase every trace of this former subservience from the documents, they managed to paint a distorted picture of the events, renaming the Great = “Mongolian” conquerors into fable-like savage cannibals, thus making a very explicit distinction between them and the Russian Horde, which had really existed back in the day.

Apart from that, the true history of the “Mongolian” conquest hasn’t been completely erased, but rather misdated to an epoch in the distant past – approximately the VI century B. C., transforming into the “great migration” and the Slavic conquest of Europe. We shall discuss this in detail below.

The gigantic “Mongolian” (Great) Empire of the Horde and the Atamans, whose formation took place in the XIV century, apparently split up later, in the XVII century, the three main parts being as follows (for the time being, we shall leave out the imperial territories in Africa and America):

Russia – the Orthodox Christian part of the Empire.

The Ottoman (or Ataman) Empire, later to be known as Turkey – the part of the Empire that became Muslim.

Western Europe, or the part of the Empire that became Catholic, or Latin, or Reformist.

Starting with the XVII century, each of the three parts has been ruled by a Czar, or an Emperor, of its very own:

the Russian Czar, or Emperor,

the Turkish Sultan,

and, finally, the Emperor of Austria and Germany, who had retained the name of Habsburg by sheer force of inertia. This old name, which had originated in the Horde, attained a drastically new meaning in the Western Europe. We shall discuss the identity of the former Habsburgs regnant in the XIV-XVI century in CHRON7.

For the meantime, we have to point out that the host of the new local rulers regnant in the Reformist Western Europe of the XVII century had still been formally subordinate to the Emperor of Austria and Germany, even if his power was just nominal.

5.3. A general view of the Eurasian map.

So what do we end up with? Our opponents might indignantly enquire about whether or not we are trying to claim that the Russians had once conquered the whole world, transforming a great many countries into provinces of their empire, all by themselves? Could Russia, or the Ataman Empire, have defeated every single other country there was unassisted? This is impossible.

Our answer shall be as follows. Firstly, the legend of one nation that had conquered the whole world isn’t ours – this is precisely what Scaligerian history tells us when it reports the grandiose invasion of the “Tartars and Mongols” and the foundation of the enormous Mongolian Empire, which had spanned almost the whole world known in that epoch. Moreover, historians tell us explicitly that the conquest of the world was on the political agenda of Mongolia back in the day.

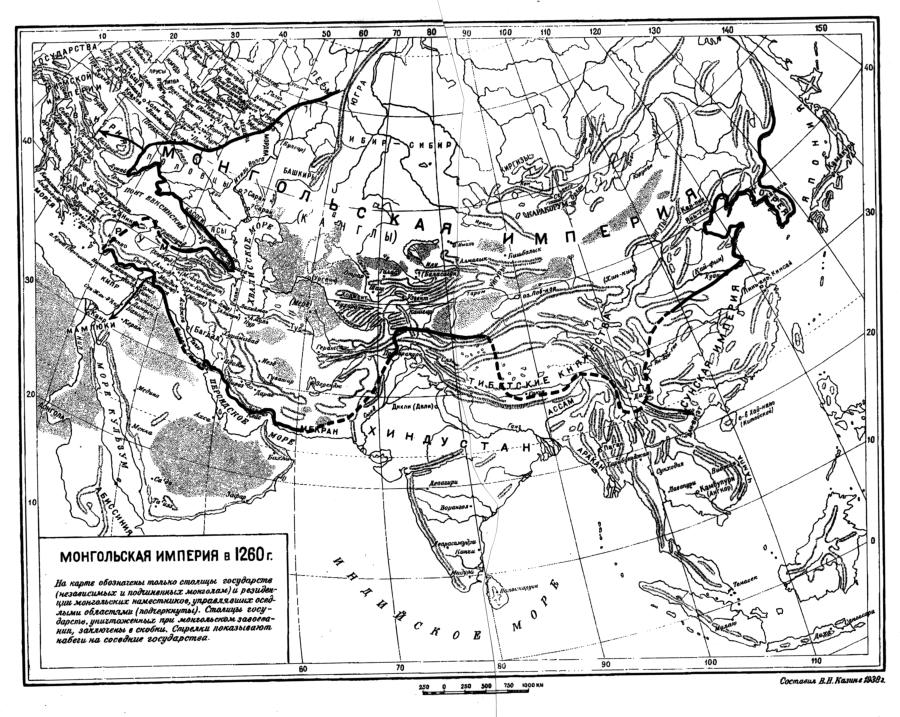

Take a look at the Scaligerian map of the “Mongolian” campaigns (fig. 8.8), which was taken from [197]. We see the “Mongolian” Empire in the alleged year 1260. In fig. 8.9 historians depicted the Scaligerian “Tartar Mongolia” of 1310. We have collected the information from both maps and reproduced it in fig. 8.10, shading the territory of the empire as it was in the alleged year 1310 so as to emphasise the greatness of its size.

Furthermore, historians themselves have represented further expansion of the “Tartar Mongols” with arrows pointed at the West of Europe as well as Egypt, India, Japan, and the South-East of Asia – Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, Burma, Indonesia and so on . . . Characteristically enough, the modern commentators who have compiled the map in fig. 8.9, were cautious enough to indicate the directions of the “Mongolian strikes as arrows and nothing but, apparently having made the “tactful” decision to refrain from representing further expansion of the “Mongolian” Empire’s XIV century territory accordingly. The arrows are there, and the results were left “unnoticed”, as though they were nonexistent. This cautious position of the cartographers is easy enough to understand – as we understand nowadays, the Empire expanded greatly in the XIV century, having stretched wide enough to include the better part of America, for instance, qv in CHRON4 and CHRON6.

Coming back to the Scaligerian map in figs. 8.9 and 8.10, it has to be noticed that historians particularly avoided representing the Western borders of the Empire. As we realise today, in the XIV century the Western Europe also became part of the “Mongolian” Empire. However, let us reiterate that the Scaligerian map fig. 8.10 only reflects the very first stages of the “Mongolian” question, which did in fact begin in this manner. Further conquests of Russia (or the Horde) and the Ottoman (Ataman) Empire, and the most important ones, at that, aren’t reflected in any way at all. Therefore, we shall have to compile a new map of the “Mongolian” Empire in the XIV-XVI century, which will be more or less complete, as seen below.

The “Mongolian” (“Great”) rulers believed the conquest of the whole world to be their mission. This mission was fulfilled with complete success. Although the Great = “Mongolian” Empire did split up three hundred years later, this was only because of the internecine wars that broke out within the Empire.

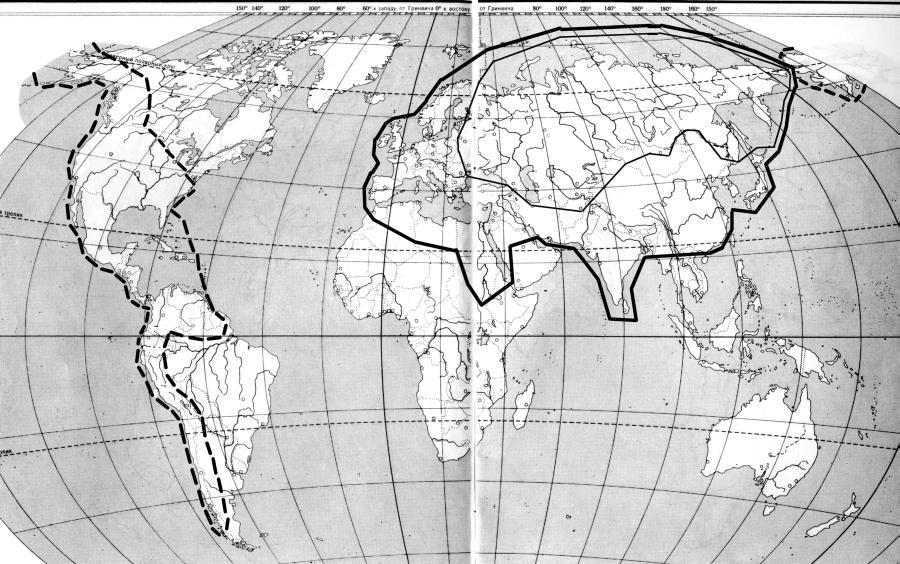

Let us now consider the geographical map of the world as shown in fig. 8.11. The thin line corresponds to the borders of the Russian Empire (in the beginning of the XX century, for instance). Now let us add thereto the lands that had comprised the Great = “Mongolian” Empire, or Great Tartary, as it was called in the XVII-XXVIII century. For this end we can use the 1754 map of Asia that we’re already familiar with in fig. 1.25, and a map of Asia compiled in the XVIII century, qv in fig. 1.28.

As we can see from both these ancient maps, as well as all the other maps compiled around that time, Great Tartary and the domain of the Great Moguls, or Mongols, included nearly all of Asia and a substantial part of Europe. Among them, in particular, we find the greater part of the modern China, India, Persia, Korea etc.

Let us now add the following countries to the territory of this Great Tartary:

The allied Ottoman (Ataman) Empire, further renamed Turkey, which was conquered by Tamerlane, or Timur.

The part of Egypt that was conquered as a result of the “Mongolian” Yellow Crusade of the alleged XIII century.

Eastern and Central Europe colonised by Batu-Khan ([796]).

These countries were conquered by the Great = “Mongolian” Empire according to the historians themselves – none of this information is new to anyone. The territory of the “Mongolian” Empire expanded to comprise the abovementioned territories in the XIV century.

However, the picture is incomplete. Let us now add the countries that had de facto proclaimed themselves vassals of the “Mongolian” = Great Empire, according to the mediaeval evidence that we cite, without providing anything in the way of organised military resistance. Those appear to include the whole of Germany, France, Italy, Britain and Scandinavia – the entire Western Europe, or, to be more precise, Europe as a whole. The resulting territory is represented by a thick uninterrupted line in fig. 8.11, which spans the borders of the “Mongolian” Empire in the epoch of the XIV century.

Then, in the XV-XVI century, the Empire expanded significantly once again during the conquest of the “promised land” by the Horde and the Ottomans = Atamans. The Great Empire gained new provinces in North and South America. The borders of these “Mongolian” territories are represented in fig. 8.11 as a dotted line. See more in re this stage of colonisation in CHRON6.

One sees the borders of the Russian Empire in the beginning of the XX century drawn as a thin line – all of it is enclosed within the borders of the “Mongolian” Empire (thick outline). We can add thereto the countries that pertained to the sphere of influence of Russia as parts of the USSR between 1945 and 1985. How does the territory of the “Mongolian” (Great) Empire of the XIV century differ from that of the Russian Empire (in the middle of the XX century, for instance)?

The former was just twice as large as the latter – several hundred years after the divide of the Great Empire. If we’re to compare it to the “sphere of influence” of the USSR in the middle of the XX century, the difference shall be even smaller – let alone the fact that the area of Alaska, which was leased to the USA under Alexander II, is comparable to the area of the Western Europe. The Romanovs finally sold Alaska to the USA in 1867, and for a small sum at that – a mere 7.2 million dollars ([942], page 136) – “so as to maintain a good relationship”, for one reason or another; this is tantamount to giving it away for free.

In fig. 8.11 we also see the American territories colonised in the XV-XVI century by Russia, or the Horde, qv in CHRON6. Incidentally, most of these territories are covered by many “Indian” burial mounds, qv in CHRON6, Chapter 14:27. CHRON6, Chapter 14 tells the readers more about the conquest of the American continent by Russia (the Horde) and the Ottoman (Ataman) Empire.

Comment: One needn’t think that the Great = “Mongolian” Empire was a rigidly centralised state. The formation of an enormous monolithic Empire that would exist for ages was impossible – owing to the imperfect means of communication, for instance. Thus, the Great Empire of the XIV-XVI century lasted for some 300 years and fell apart after that. However, the very concept of a united multinational Empire remained appealing for a great many people, surviving in many of its former parts.

5.4. The opposition between the Atamans and Russia, or the Horde. The part played by the Romanovs.

At the end of the Great Empire, in the XVI-XVII century, the relations between Russia, or the Horde, and the Ataman Empire, were excellent. However, the Ottoman = Ataman Empire was a menace to the Westerners, and a great one at that. This is recognized in Scaligerian history as well – it is reported that the Ottomans reached Vienna in the XVI century. In CHRON6 we shall demonstrate that the Scaligerian version of these events is very distant from the truth. The conquest of the “Mongolian” Europe by the Ottomans, or the Atamans, was of a secondary nature.

The East became a very real menace for the Western Europe once again, for the second time since the conquest of the XIV century. Apart from that, the book of Sigismund Herberstein ([161]) makes it obvious that Russia was seriously considering getting engaged in warfare, which made the Western Europe of the XVI century face two formidable adversaries.

Apparently, the West, realising its inability to provide adequate military resistance, chose another method – one that eventually turned out successful.

First of all, the Westerners managed to sow discord in the ranks of the Horde’s ruling class by the elevation of the Romanovs. In CHRON4 we give a detailed account of how the former regnant dynasty of the Horde was overthrown as a result of this power struggle – moreover, it was exterminated physically. Later on, already under Alexei Mikhailovich Romanov, they succeeded in making Russia an enemy of Turkey and directing all the military endeavours of the former in the direction of the latter for centuries on end – the two countries remained hostile for two hundred years, no less. This appears to be how the reformist Western Europe protected itself from a second rout.

Coming back to the part played by the Romanovs in the whole scenario, one cannot fail to notice the pronounced pro-Western orientation of the Romanovian dynasty over the whole course of its history, spanning almost three hundred years starting with the XVII century. One particular consequence of their Occidental leanings is very important indeed – the regnant dynasty of the Romanovs made all educated Russians dogmatic about the alleged cultural supremacy of the West over Russia. This theory was instilled in Russian mentality so deeply that even the most radical Slavophiles were taking it for granted, believing said supremacy to be obvious and self-implied; many share this view until the present day. The idea of Russia being a “backwards country from the very start” and the “savage nature” of its denizens as compared to the enlightened gentlefolk of Europe was planted in the consciousness of the Russian people so firmly that it was even shared by most of Russia’s finest minds, with only a few exceptions.

Apparently, this dogma was instilled in the people’s minds under the Romanovs and not any earlier - as blatant propaganda, since it clearly wasn’t based on reality. However, Russian culture had differed from the Western greatly, and so the Romanovs, originating from the West originally, must have genuinely believed in the inferiority and barbarism of Russia. Apart from that, they managed to make the educated part of the Russian nation believe in its own inferiority and idolise the West and its culture. The thinkers who tried to question this dogma (such as M. V. Lomonosov, A. S. Khomyakov and so on) were declared “rabid Slavophiles” or simply incompetent ignoramuses.

Nobody noticed anything about Russia (or the Horde) being a backwards country before the Romanovs, which is also made obvious by the mediaeval documents cited herein. There weren’t any reasons for considering Russia inferior to the West during the reign of the Romanovs, either – all of it was nothing but propaganda.