Part 3.

Scythia and the Great Migration. The colonization of Europe, Africa and Asia by Russia, or the Horde, in the XIV century.

Chapter 9.

The Slavic conquest of Europe and Asia. A rare book of Mauro Orbini about the “Slavic Expansion”.

1. Did the Western Europe remember the “Mongolian” conquest to have been undertaken by the Slavs?

We have already said a lot about Mongolian (or “The Great”) Empire having been Russian for the most part, or a Slavic state of the XIV-XVI century, seeing as how the Russians, or the Slavs, have been the primary driving force behind the expansion of the Empire, qv in CHRON4. At the same time, the Empire was populated by a great many different ethnic groups.

However, one might come up with a natural objection. How could such a grandiose historical event as the foundation of a global empire by the Slavs in the Middle Ages have become completely erased from the collective memory of the Western Europe? If the Empire had really existed in the XIV-XVI century, people must still have remembered it in the XVII-XVIII century. How could the Europeans have forgotten the true identity of their conquerors, confusing their neighbours from Scythia for some wild “Mongolian” tribe of nomads from China?

Indeed, the Romanovian historians have always been emphasising the “non-Slavic” origins of the “Tartar invaders”. However, we demonstrate this to be incorrect in CHRON4, since the West Europeans also used the term “Tartars” for referring to the Slavs. At any rate, the invasion of the Great, or “Mongolian” Horde has remained in the memory of the Western Europe as the barbaric “Tartar invasion” that we have already covered in great detail, qv in CHRON4.

However, the question remains: do the West Europeans remember anything about a Slavic invasion of similar proportions? It turns out that they do, and very vividly indeed – however, the Scaligerian version of European history moved this invasion into the alleged VI century B. C. One must say that it is usually represented rather poorly in history textbooks, and with much caution, although certain special monographs cover it at length.

This is, for instance, what B. A. Rybakov has to say on the matter. “The breakpoint in the history of all the Slavic peoples falls over the end of the V and the VI century A. D., which is when the great migration of the Slavs began. It has resulted in a complete transformation of the map of Europe” ([752], page 7). It was a large-scale Slavic invasion, which had engulfed the Balkans, Germany, Greece and large parts of the Western Europe. Actually, historians still consider the Slavic populace of Greece and the Balkans to be the descendants of the “Avarian Slavs”, or the VI century conquerors of these lands ([195], pages 40-41). See also [956], pages 178-179. This issue is covered in many publications. A voluminous bibliography can be found in [956], for instance.

The Slavs have lived all across the modern territory of Germany; among them – the famous mediaeval Venedes. Could the names Vienna and Venetia be derived from the name of this nation, which, in turn, stems from the Slavic word for crown (“venets”). The history of the Slavic invasion was studied with particular diligence in the XVIII-XIX century Germany.

B. A. Rybakov reports the following: “The VI century authors [or the chroniclers of the XV-XVI century, according to the New Chronology – Auth.] say that several substitutes of the name ‘Venedes’ were commonly used in their epoch – in particular, ‘Slavenes’ (the letter Kappa between S and L is silent) and ‘Antes’.

The tribes from the proto-Slavic habitat were known as Venedes, or Venetes. The Finns and the Estonians still call the Russians “Vana” – a revived ancient name from the epoch of Tacitus.

It would be perfectly acceptable to assume that . . . ‘Slovene’ used to stand for ‘settlers from the land of the Vene’, since colonists and settlers were referred to as “sely”. The name ‘Slavenes’ or ‘Slovenes’ could have been used by the tribes that had left the proto-Slavic habitat, but were nonetheless eager to use the ancient collective term for referring to themselves” ([752], page 21).

Everything is correct here, with the sole exception of the chronology. According to our reconstruction, the above is a de facto account of the Russian (or Mongolian”) conquest of Europe in the XIV-XV century A. D., which has got nothing to do with the V-VI century, despite the consensual assumption. The shift of the dates roughly equals a thousand years.

Where did the Slavic conquerors come from, anyway? There are many theories about this; however, their homeland is usually located in the East or the Northeast. There is also a point of view that insists on a very explicit localization of the geographical origins of the Slavic settlers. Falmerayer, a German scientist of the XIX century, refers to a number of documents to prove that the Slavic invasion of the VI century A. D. began from Kostroma – the very centre of Russia, in other words.

According to A. D. Chertkov, “The Slovenes were even supposed to have come from Scandinavia two hundred years before the fall of Troy . . . They were often confused for the Sarmatians, the Scythians, the Avars, the Volga Bulgars, the Alans etc . . . Falmerayer insists that they came from Kostroma [sic! – Auth.], whereas Shafarik names the lands beyond the Volga and Sarna” ([956], pages 178-179). This is precisely where the “Mongols” are believed to have come from later on – from Saray and the Volga region.

Let us remind the reader that, according to our reconstruction as related in CHRON4, the capital of the mediaeval Russia, or the Horde, and the headquarters of the Russian Great Prince (or the Mongolian Khan) in the XIV century were located in Kostroma. It was the headquarters of the Russian Great Prince, and a close neighbour of Yaroslavl, or Novgorod the Great. This is whence the armies of Ivan Kalita, or Batu-Khan, began their movement Westwards, heralding the famous “Mongol and Tartar” invasion of the XIV century A. D., later misdated to the XIII century. It turns out to have become reflected in the works of later authors as the Slavic invasion of the alleged VI century.

One needn’t think that before this time, or the XIV century, the Slavs had not resided in the Balkans. The Balkans appear to pertain have always been comprised in the traditional Slavic habitat. However, the Russian and Tartar (or the “Mongol and Tartar”) invasion of the XIV century has brought the Slavs to other parts of the Eurasian continent – Germany, Greece, etc. The fact that the invading armies had swarmed the Balkans as well does not contradict the fact that the Slavs had been residents of this peninsula before that. Incidentally, Empress Catherine the Great wrote such things as “the word ‘Saxon’ derives from ‘sokha’ [the Russian for “plough” – Trans.] . . . The Sokh-Sons had Slavic ancestors, likewise the Vandals and many others” (Russian National Document Archive, F. 10, Op. 1, D. 17). Modern historians cannot help from noting patronizingly that some of her observations “cannot fail to make one smile” ([360], page 94).

And so it turns out that the memory of the XIV century invasion of the Slavs had still been very much alive in the XVII century Europe. However, the chronologists of the XVI-XVII century have misdated it to the distant past, either deliberately or by accident. As a result, the invasion has spawned numerous vicarious reflections of itself on chronicle pages, transforming into the endless “ancient and early mediaeval” Slavic conquests of Europe. And yet the chronologists have managed to make the Slavic conquest extremely ancient and legendary to a certain extent. Apparently, the Western chronologists of the XVI-XVII century must have thought it to be less of a blow to their pride as an event of the faraway VI century.

According to our reconstruction, all the “ancient” and “early mediaeval” conquests of Europe by the Slavs are nothing but carbon copies of the Russian “Mongolian” conquest of the XIV-XV century, or the extension of the latter, namely, the Ottoman (Ataman) conquest of the XV-XVI century.

2. Why did Peter the Great build St. Petersburg amidst the swamps? The book of Mauro Orbini.

In the present chapter we shall once again relate the history of the Great = “Mongolian” conquest – this time according to the sources that explicitly interpret it as a Slavic invasion.

It is noteworthy that some of these sources have survived until the present day. As we realise today, all such sources were being systematically and deliberately destroyed – in Western Europe as well as the Romanovian Russia. As we shall see, this destruction campaign was one of the main reasons why the Catholic Church drew up the famous Index of Forbidden Books. It’s very first version was compiled in Vatican, Italy, and dates from 1559 A. D. ([797], page 488). The very middle of the XVI century, that is. All the books included in said index were destroyed methodically in every part of Europe. In Russia, the destruction of books began in the XVII century, after the ascension of the Romanovian dynasty. We wrote a great deal about it in CHRON4.

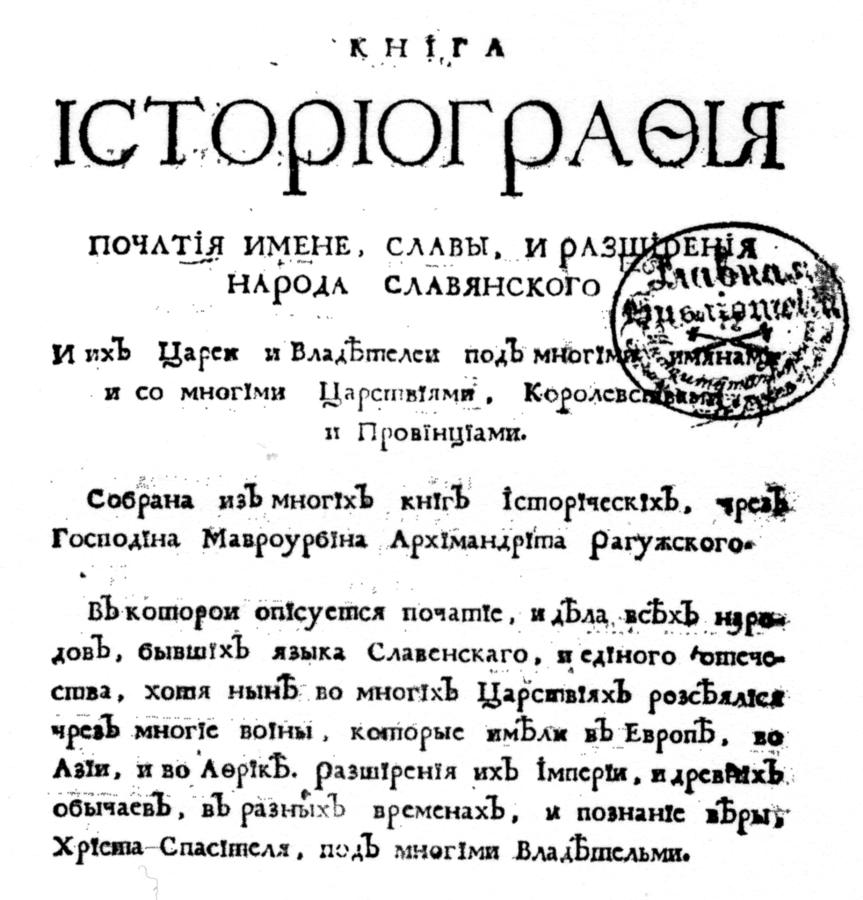

Fortunately, there are exceptions to every rule. A few sources have survived. After a long search, we have managed to find a whole book that falls in this category – of great enough interest and importance for us to find it worthy of a whole chapter. It is the book of Mauro Orbini (or Maurourbinus, as the name is transcribed in the actual book). See fig. 9.1:

The book on the Historiography of the name, the glory and the conquests of the Slavic nations, their kings and their rulers of many a name, as well as their numerous domains, kingdoms and provinces.

Compiled from a wide variety of historical books by the noble Maurourbinus, Archimandrite of Ragusa.

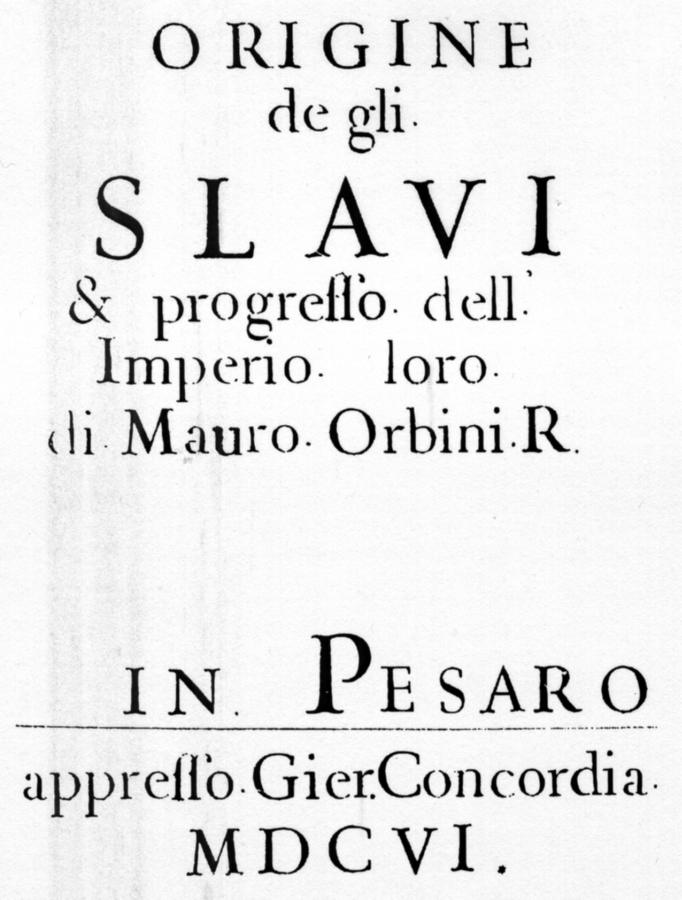

The book was written in Italian and published in 1601 ([797], page 931). The Russian translation came out in 1722. Orbini died in 1614 (ibid). In fig. 9.2 we reproduce the first page of the Russian edition of 1722, and in fig. 9.3 – the title page of the 1606 Italian publication.

As it is stated in the title of the book (fig. 9.1), Orbini was the Archimandrite of Ragusa, thus occupying a very high position in the ecclesiastical hierarchy of that city, which still exists in Sicily ([797], page 1087). Apart from that, Ragusa was the former name of Dubrovnik, the city in the Balkans ([797]). Since the book was written in Italian, and contains clear indications that Orbini had used Italian libraries, it is most likely that he was the Archimandrite of Ragusa in Italy. However, this issue is of minor importance to us.

What does the book tell us? According to what the Soviet Encyclopaedic Dictionary ([797]) demurely tells us, “Orbini’s book entitled ‘The Slavic Kingdom’ . . . attempts to relate the history of all the Slavic nations and to demonstrate their unity, proposing the theory that the origins of the Slavs were Scandinavian” ([797], page 931).

If one is to believe this brief passage, one might get the notion that Orbini’s book is rather tedious, and that its author adheres to some preposterous theory about the ancestors of the Slavs hailing from the territory of the modern Scandinavia. This would hardly make anyone eager to read it, especially given its extraordinarily limited availability. The logical assumption is that it hasn’t seen any newer editions since 1722 for a good reason. Even the edition of 1722 must therefore owe its existence to nothing else but the direct orders given by Peter the Great, who was obsessed with the idea of transferring the capital of the Russian Empire closer to Scandinavia, or the alleged ancient homeland of the Slavic conquerors of Europe. This idea of his resulted in the foundation of St. Petersburg.

The book of Orbini must have impressed Peter the Great deeply. It appears as though the latter was harbouring the wish to return to the historical homeland of the Slavs and to revive the ancient glory of their empire. Unfortunately, he was interpreting the quotations from the “ancient” authors as collected by Orbini in too literal a manner – namely, the claims that the Slavs had launched their conquest of the world from a certain land of Scandia. As we shall see below, in the chapter dealing with the Scandinavian historical tractates, the “Scandia” as mentioned by the ancient authors was really Scythia, or Russia (the Horde), and not the modern Scandinavian Peninsula, whose original name is “Scandia Nova”, or “New Scandia”. These northern territories were colonised by the Horde during the “Mongolian” conquest.

Still, Peter the Great must have been unaware of this fact, already forgotten by his time – accidentally by some and deliberately by others. Hence the choice of the northern swamps as the site of the future capital. A propos, the creation of a “maritime gateway to Europe” did not necessarily stipulate the transfer of the capital to the shores of the Baltic Sea.

One must emphasise that the Russian edition of Orbini’s book came out as a result of a direct order given by Peter the Great. The title page of this edition tells us the following: “Translated from Italian to Russian and published at the order of Peter the Great, Emperor and Autocrat of All Russia etc, in the epoch of his glorious reign. The typography of St. Petersburg, 20 August, 1722” (see [617]).

Moreover, not only did Peter the Great give out orders for the translation of Orbini’s book – he actually insisted on supervising the translation personally, which is quite extraordinary in itself. For instance, in 1722 he wrote a special letter to the Senate, which we quote in accordance with its Serbian translation, since the text of the letter became known to us from a book in Serbian ([341]): “The book about the Slavic nation translated from Italian by Sava Vladislavich [Orbini’s oeuvre – Auth.], as well as the book of Prince Kantemir on the Mohameddan Law, must be sent to us immediately if said books have already been published. If not, by all means give orders for their publication and have them sent to me immediately” (quoted in accordance with [341], pages 344-345).

The fact Peter was interested in Orbini’s book this much gives one the impression that his plan of transferring the capital to St. Petersburg must have had other reasons than the mere wish to have another seaport on the Baltic coast. We sense some global political idea behind it – the return to the original hotbed of the Slavic conquest of the world. Since Peter didn’t manage to conquer the world from Moscow, failing time and again, he may have made the conclusion that Moscow was unfit for serving as the starting point of his invasion.

However, Peter was obviously mistaken here. Moscow, of all places, didn’t have any shortcomings in this respect. The failures of Peter (and the Romanovs in general) must have an altogether different explanation. Apart from that, as we have pointed out above, the Romanovs were striving to move their capital away from the dangerous proximity to the Muscovite Tartary in the XVII-XVIII century (see CHRON4, Chapter 12). This is why they were forced to choose the shores of the Gulf of Finland as the site of their capital city. This location would make it easier for them to flee towards their allies in the Western Union in case of an invasion from Tartary.

One must reflect on the ambiguous role of the Romanovs in the history of Russia. On the one hand, they have usurped the throne as the pro-Western dynasty, defeating the Horde, thus making the West independent from Russia to a great extent, qv in CHRON4. On the other hand, having come to power and immersed themselves into the atmosphere of Russian life, their initial pro-Western orientation gave way to other priorities of a more Eastern nature. In a way, this pro-Western orientation was “digested” by Russia.

Having found himself the ruler of an empire, Peter the Great must have decided to revive its world domination, remembering that relatively recently a large part of Europe and Asia were part of Russia, or the Horde, and harbouring ambitions to restore the former borders of the empire.

In general, Peter had clearly enjoyed Orbini’s book, which is why it has miraculously survived in Russia. As we shall soon see, if it hadn’t been for Peter, Orbini’s text, which ended up in Russia, wouldn’t have survived until our day and age, since what Orbini actually writes about is completely different from how it is coyly presented by the “Encyclopaedic Dictionary”.

3. The conquest of Europe and Asia by the Slavs according to Orbini’s book.

The book of Orbini doesn’t need our commentary. We shall merely provide a number of quotations from it, occasionally making the narrative style less archaic, but always keeping the old spellings of personal and geographical names as well as the original punctuation.

This is what Orbini writes in his book:

“The Slavic nation fought against nearly every nation in the world. The Slavs laid Persia waste, and were the rulers of Asia as well as Africa, battled the Egyptians and Alexander the Great; they conquered Moravia, the Schlenian land, the Czechs, the Poles and the shores of the Baltic Sea, moving towards Italy and waging countless wars on the Romans.

They were occasionally defeated; sometimes they would put the Romans to rout on the battlefield, or proved the equality of the two forces.

Finally, having conquered the Roman Empire, they became the masters of the numerous Roman provinces, wreaking havoc and desolation on Rome and making the Roman Caesars pay them tribute – a feat unrivalled by any other nation.

The Slavs were the owners of France and England. They made Spain their dominion and took over the best European provinces.

This glorious nation was the predecessor of many a strong people: the Slavs, the Vandals, the Burgontions [the natives of Burgundy in modern France – Auth.], the Goths and the Ostrogoths. Their offspring also includes the Russians (or the Racians), the Visigoths, the Hepids, the Getyalans [the Alanian Goths – Auth.], the Uverl (or the Grul), the Avars, the Scyrrs, the Gyrrs, the Melanden, the Bashtarn, the Peucians, the Dacians, the Swedes, the Normans, the Tenn, or the Finns, the Ukrians [Ukrainians, perhaps? Or, alternatively, the Ugrians (Hungarians) – Auth.], the Marcomans, the Quads and the Thracians.

The Alleri were the neighbours of the Venedes, or the Genetes, which had populated the Baltic coast, and gave birth to the following: the Pomerans [the Pomeranians, no less! – Auth.], the Uvil, the Rugians, the Uvarnav, the Obotrites, the Polabs, the Uvagir, the Lingons, the Tolens, the Redats (or Riadutians), the Circipanns, the Quisin: the Erul or the Elueld, the Leubus, the Uvilin and the Storedan; also the Bricians [the Brits, or the Bretons! – Auth.],

All of which constituted the very Slavic nation” ([617], pages 3-4).

In brief, the above formulates the primary result of Orbini’s historical research, which is why he puts it the very beginning of his book. The rest of the text deals with explanations and details.

This fact alone makes his research in history perfectly sensational to the modern reader – however, Orbini himself did not count at making any sensations.

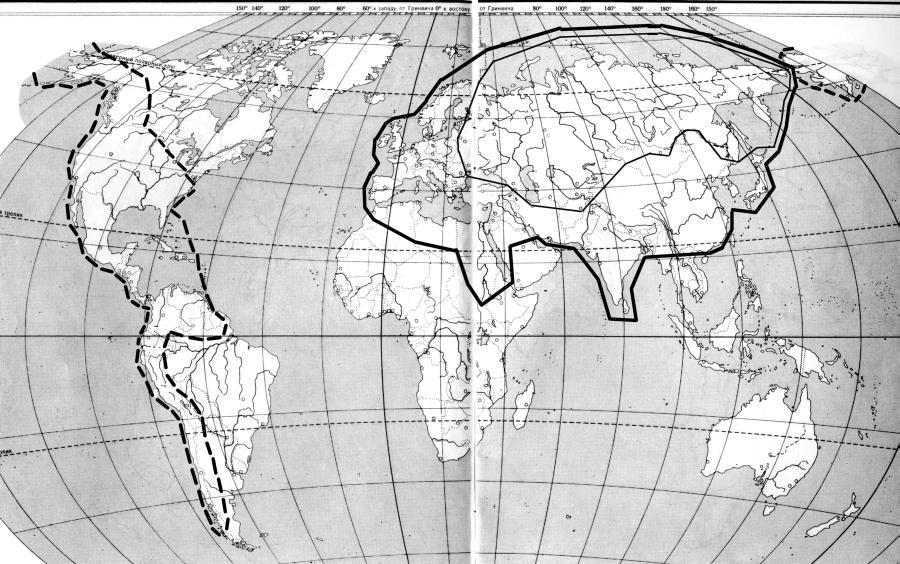

And so, what do we learn from the above passage? A great many things – for instance, the fact that the Slavs had owned Asia, Africa and Europe. This claim is explained perfectly well by our reconstruction, qv in fig. 8.11.

In particular, Orbini tells us that the Slavs had ruled over France, England, Spain, Italy, Greece, the Balkans (Illiria and Macedonia), the Baltic coast and the best European provinces in general.

Moreover, the Slavs are named as the ancestors of many European nations that are considered to have nothing in common with the Slavs today, among them:

The Burgundians, or the inhabitants of Burgundy, which became a French province in the XV century, the Swedes, the Finns, the Western and the Eastern Goths (referred to as Visigoths and Ostrogoths), the Alanian Goths, the Dacians, the Normans, the Thracians (or simply the Turks), the Venedes, the Pomeranians (natives of Pomerania, comprised of Germany and Poland), the Brits or the Bretons (Orbini calls them Bricians), and the Avars.

Let us emphasise that nearly every claim made by Orbini is confirmed by other independent sources as well, in particular, the “ancient” Scandinavian historical tractates, qv below. This makes his information all the more valuable, and proves it to be more substantial than “mere fantasy”, as many would probably like to believe.

It is possible that some of our readers might find Burgundy to be a particularly unlikely entry in the list of countries whose natives were populated by the descendants of the Slavs. We have to say that the geographical atlas of Prince of Orange ([1018]) that came out in the middle of the XVIII century refers to Burgundy as to Burgognia. The name is a likely derivative of Gog, and we already know that Gog and Magog were the names of the “Mongolian” Russia, or the Horde.

The area in the South of France (around Toulouse and near the Spanish border) is known as Rousillon, which is the name we find in the abovementioned atlas as well as many other maps of the XVIII century. The name is likely to be a derivative of the name “Russian”. It must have once stood for “Russian Ilion” (or “Russian Troy”), “Russian Lions” or “Russian Alanians”).

The most vehement opponents of Orbini might concede to that with much reluctance, but will be clearly infuriated by Orbini’s claim about the Slavic origins of the Brits (the denizens of the ancient Britain) or the Bretons in France.

They might be wrong about this matter. Orbini might well be correct in the claims that he makes. Indeed, let us remind the reader that in CHRON4 we demonstrate Scotland and Ireland to be closely related to Russia. In particular, Scotland (or Scotia) is an old name of Scythia, which has ended up in the West as a result of the Great = “Mongolian” conquest, qv in CHRON4. Moreover, the same mediaeval Atlas of the Prince of Orange ([1018]) uses the name “Ross” for referring to the largest area of Scotland, as one sees from the ancient maps that we cite in CHRON4, Chapter 18:11.

Therefore, the potential critics of Orbini should be more careful with accusing him of making “absurd” statements.

The more resilient opponents might carry on in the following manner. They might agree to the fact that the mediaeval Scandinavians confirmed Orbini’s claims. However, if that is indeed the case, how come these historical facts were firmly forgotten in the XVIII-XIX century? Could it be that historical science made such advances by that time that the educated people of the XIX century were already unable to lend any credulity to such “nonsense” as Orbini’s theories?

Apparently, it turns out that certain well-established scientists of the XIX century actually pointed out the same historical facts as Orbini – in particular, the famous Russian historians M. M. Shcherbatov ([984]) and A. D. Chertkov ([956]), as well as A. S. Khomyakov, a prominent Russian scientist and philosopher and a host of others. We shall refrain from quoting their works at length, since the book of Orbini already contains most of the facts related therein.

4. Our conception explains the book of Orbini.

Scaligerian history makes Orbini’s book look perfectly preposterous. Our conception allows a new appreciation of his work, making it a lot less bizarre to the extent of being completely rational. Indeed, if the “Mongolian”, or the Great Conquest was Slavic for the most part, there is nothing surprising about the fact that many nations of the Western Europe have Slavic blood running in the veins, which is what Orbini actually claims.

Simultaneously, our conception does not require any proof from the part of Orbini. On the contrary, his claims about the Slavic origins of many Western European nations in the epoch of the Horde’s expansion (the XIV century) only begin to make sense within the framework of our New Chronology, based on statistical results as related in CHRON1-CHRON3.

Let us once again remind the reader that Orbini must have been a Western European author, and that his opinion is also of interest to us as the opinion of a Westerner.

5. The parties that went to battle and won, and the ones that lost, but wrote history.

Orbini begins his book with a very deep observation, which we realise to be perfectly correct. Some nations went to war; others wrote historical works in their wake. We shall briefly formulate it in more modern terms, quoting a corresponding fragment of Orbini’s book for the sake of completeness (bear in mind that his oeuvre came out in 1601).

“We should by no means be surprised that the fame of the Slavs isn’t as great nowadays as it used to be. Had there been as many learned men and writers of books among the Slavs as there were fine warriors and makers of weapons, their glory would be unrivalled by any other nation. As for the fact that many other nations, greatly inferior in the days of yore, exalt their glory to the heavens today, it is only explained by the labours of their scientists” ([617], page 1).

Whenever we read a historical chronicle today, we are inevitably influenced by the nationally subjective point of view of the chronicler. Each one would obviously try to make his own nation look as good as possible. The battles won by the fellow countrymen of a given scribe, no matter how minor, were described with particular eloquence. Other battles, which had resulted in the defeat of the chronicler’s people, would be covered very sparsely, or not at all.

This is perfectly natural and understandable to everyone. However, some might lack the awareness that this fact needs to be constantly borne in mind when one reads old chronicles.

Orbini proceeds to make the observation that the existence of a historical school whose works have survived until our day in a given country has got nothing in common with the military prowess of said country’s inhabitants. Some nations of victorious warriors did not write any grandiose historical tractates, whereas other nations with a much lower military potential would sometimes compensate by the creation of historical chronicles that would greatly exaggerate their own military power, as well the importance of the role that they played in history. Defeats on the battlefield were compensated by victories on chronicle pages. This practice was particularly common in the Middle Ages, given that literacy was a luxury and that national historical schools were few and far between.

Basically, Orbini is telling us that the Slavs did not have a well-developed historical school in the past. Alternatively, as we begin to realise, the works written by the representatives of that school, haven’t survived until our day and age – nor have they reached Orbini. There might be a variety of reasons to explain this – in particular, the destruction of certain historical oeuvres during the Reformation epoch of the XVI-XVII century. On the contrary, such historical schools did get founded in a number of other countries, Italy in particular. The version of the ancient history that we learn today is largely based on the viewpoint of said schools’ representatives of the XVII-XVIII century.

This is the very reason why Italian Rome is believed to have prevailed over the rest of the “ancient” world. The iron legions that had reputedly crushed the barbarian armies (the Germans, the Slavs and so forth) only did so on paper. In reality, the real military victories of Rome as the Horde became ascribed to other nations.

Paper will tolerate anything that may be written on it. Yet such “paper theories” aren’t always harmless. Some gullible fans of the “historical might and power of the ancient Italy” tried to restore the former glory of the Roman Empire in the XX century, Mussolini being the best example. The beauty of the paper myth collided with reality; what happened next is known to everyone.

The part played by Italy in world history and culture is famous and indisputable, be it architecture, art, opera or literature. Italy was one of the most influential European countries in the XVI-XVIII century, insofar as culture is concerned.

But why must one necessarily complement it by the fame of the alleged conquerors of the whole world and the masters of Germany, Gaul, England, Spain, Persia, Egypt, the Balkans and the Caucasus, as the Scaligerian history has been doing all along?

Psychological observations. Primo.

If we are to imagine the Scaligerian version in modern terms, we would see the divisions (or legions) of modern Italy invade Germany, conquer France, Spain and Portugal, then Romania, Austria, Greece, Serbia, Croatia and Bosnia, subsequently annexing Turkey, Syria, Palestine, Iran and Iraq, crossing the English Channel and conquering Britain, and, finally, they would become the masters of Egypt, Algeria and Morocco.

We are simply providing a list of the countries which the Scaligerian version of history believes to have been conquered by Italian Rome in the “ancient times”.

The balance of military supremacy inevitably shifts as times go by. But can it shift quite as greatly? The actual history of the last few centuries demonstrates that notwithstanding said supremacy shifts, the military balance remains pretty much the same as time goes by.

Secundo.

We might be asked about the reasons why the Russians have never managed to reflect their remarkable military advances in chronicles. After all, the Italians managed to write a great deal about their nonexistent victories. Why were the Russians so modest?

Our reply would be as follows. Modesty has got nothing to do with it – the real reason is the de facto defeat of Russia, or the Horde, on the political arena of the XVII century as a result of the Great Strife. Russian throne was usurped by the Romanovs, who were representing the interests of the Western diplomacy. Although Russia managed to assimilate this political invasion eventually, it had left a deep mark in Russian culture. In the XVII-XIX century the Romanovian and West European historians were diligently writing a new version of the ancient history, reserving a rather inconspicuous place for Russia. Russian chronicles of the XIV-XVI century were partially destroyed; the remaining parts were either edited tendentiously or completely re-written. The Great = “Mongolian” Empire was de facto erased from the history of the XIV-XVI century and cast into deep antiquity, creating the nebulous legends of the “Great Migration” and the Slavic conquest in the so-called “early Middle Ages”.

Furthermore, one must also account for the following psychological factor, which came into existence in the epoch of the Reformation. What we consider presently has to deal with the attitude towards advertising, no less. It is possible that in the epoch of the Great Empire advertising and self-advertising wasn’t considered important, the reasons being that the Empire had a single Emperor, or Khan, and was supported by the army, or the Horde. Competitive political advertising was unnecessary due to the absence of competitors.

History has only been used for political advertising since the divide of the Empire in the XVII century, when its Western fragments engaged in a relentless power struggle, and started to use advertising for their advantage. The importance of advertising in its capacity of an ideological weapon was realised in the Reformist West of the XVII-XVIII century without much delay; historical and political advertising must have been born in mediaeval Italy around the XVI-XVII century. One must admit that this advertising, likewise the ideology and the diplomacy that came in its wake, made the Western Europe victorious in its fight against Russia and Turkey – a success that could by no means have been achieved by military means.

The advertising of one’s own advantages has never been a forte of Russia – this state of affairs came to existence in the XVII century, and its repercussions can be observed to this very day. The West has no qualms about advertising its own successes, often exaggerating them, whereas the Russians have always been more reserved about it due to its historical and cultural tradition.

One must bear in mind that this circumstance makes it very difficult for the New Chronology to be perceived adequately – in Russia as well as in the West. Russians would find it easier to admit that, apart from the Mongols, there were two or three other foreign nations that have conquered them at some point, in the vein of the Romanovian tradition.

The reverse conception, which appears to be in much better correspondence with historical reality, often encounters an embarrassed reaction in Russia; indeed, the Russians would be likely to find themselves compromised by the conquest and colonisation of the Western Europe by their ancestors, although it was populated very sparsely, according to John Malalas, for instance – it would probably be seen as yet another proof of their alleged barbaric manners.

These emotions are doubtlessly the fruits of the Romanovian historical education to a large extent; however, the emphasis of one’s own achievements is pretty alien to the archetypal Russian character in general.

We are by no means making the New Chronology a means of aggrandising the reputation of Russia in the eyes of the Westerners. The nobility of the West and the East is of the same origin in general, hailing from the XI-XIII century Byzantium, and especially the Great = “Mongolian” Empire of the XIV-XVI century. This makes them all related to each other to some extent, although these relations have already been distant in the XVII-XVIII century. Such relations must have proved useful for the foundation and the subsequent three hundred years of expansion and development of the enormous Great (“Mongolian”) Empire. In the XIV century, a descendant of the XI-XIII century Byzantine nobility known as Genghis-Khan, and also as Great Prince Georgiy Danilovich, made himself “the first among the kin” due to the strength of the army that he had managed to create.