Chapter 12.

Western Europe of the XIV-XVI century as part of the Great = "Mongolian" Empire.

12. The knightly name of Rosh = Russ in crusade history.

Let us turn the reader’s attention to the famous mediaeval clan of De La Roche, which took part in the conquest of Greece and Byzantium in the alleged XIII century A. D. Otto, or Odo de la Roche, a crusader knight, was the ruler of Athens in the alleged years 1205-1225 ([195], page 378).

Also, “Otto de la Roche sur Lunion, Senior de Ray, belonged to one of the most distinguished families in Burgundy . . . He revealed his valour at the storm of Constantinople” ([195], page 141). He is believed to be the owner of rich Theban lands and “the founder of the surname Ray” ([195], page 141).

Many passages of the fundamental oeuvre of F. Gregorovius ([195]), a prominent German historian, tell us about the participation of numerous representatives of the de la Roche family in the wars of the XIII century, which were later described as a Trojan War, according to our reconstruction. It is likely that the French family of la Roche could trace its genealogy to the Russian conquerors of Europe, or the Horde.

Let us also pay attention to the French family of Rochefort ([729], page 171). Considering the flexion of F and T, the name is synonymous with ROSH-TR (ROSH-Tartars or ROSH-Franks). This family is also likely to be the offspring of the Russian Turks, or Tartars, of the XIV century.

We read much about the crusader knights of ROSH-TR (Rochefort) in the mediaeval chronicles that describe the wars of the alleged XIII century fought on the territory of Byzantium and Greece.

Amidst the Crusader knights we also see the natives of the French Roussillon ([195], page 378). It is possible that the name Roussillon (RUSS + ILION) was also brought to the territory of the modern France as a result of the Russian (or the Horde’s) conquest of the Western Europe in the XIV century.

It is therefore possible that a large part of the French aristocracy can trace its ancestry to the Slavs, who had once settled in these parts of the Western Europe. This is why the family names of the aristocracy preserved the roots RUS, ROSH etc. The initial meaning of these names was largely forgotten – this forgetfulness was compulsory.

Let us also recollect the French crusaders from the Brachet family, for instance, “Pierre de Brassier (de Brachet, de Brachel, de Brechal etc) . . . brother of Hugues [Gog – Auth.] de Brassier” ([729], page 172). We are likely to see a reference to P-Russia (Prussia or White Russia).

The White Horde must also have left a few traces in France after the Western Europe was swept over by the wave of the Russian conquest.

The French cleric Pierre de Rossi comes to mind as well ([729], page 172). It is also possible that the name Rogé, which was also borne by some of the Crusader knights ([136], page 295), happens to be of a similar origin.

13. Gog, the Mongols and the Tartars as Frankish crusader knights.

Considering the above, it would be interesting to take a closer look at the rosters of crusader knights who fought in Byzantium and in Greece in the alleged XIII century. Apart from such names as Roche and Rochefort, we also discover the names that are likely to be derived from Gog, the name of the Goths, or the Cossacks, according to our reconstruction, qv in CHRON4.

Let us consider the conquest of Czar-Grad in the alleged years 1203-1204 as described by Robert de Clary, author of the chronicle entitled “The Conquest of Constantinople” ([729], page 81).

He begins his book with a list of the most famous crusaders who took part in the conquest of Constantinople ([729], page 5). Among them we see the following names likely to derive from Gog and Russ: Hugues, Count de Saint-Paul, Guye, his brother, Hugues – a knight, Hugues de Beauvais, Gaultier, a knight whose name is clearly a derivative from “Goth”, Hugues, the brother of Pierre de Brassier, Rochefort – Olivier de Rochefort, Guye de Manchicourt etc ([729], pages 5 and 168).

Further on Robert de Clary names three knights named Gaultier and twelve knights named Guye ([729], page 168).

Let us also mention the crusader Hugues, Count de la Forêt, a participant of the Fourth Crusade ([136], page 292). His name sounds like GOG-TR (Gog the Turk).

In this case, one must also recollect the distinguished Frankish family of Montfort, or MON-TR – possibly, Mongol-Turk or Mongol-Tartar (Great Turk/Tartar).

Knight Geoffroi de Villehardouin, the author of the chronicle “Conquest of Constantinople”, the Marshal of Champagne and one of the leaders of the Fourth Crusade ([136], page 293) lists eleven knights named Gaultier and eighteen named Guye among the most distinguished heroes of the campaign ([136], page 292). In particular, we see Hugues de Brassier (Brachet), once again, a possible derivative of Gog B-Russian or Goth P-Russian (Byelorussian Goth).

We should also name the knights bearing the surname of Montferrat ([729], page 168), or MON-TRRT (possibly, “Mongol Tartar”).

Furthermore, Boniface I of Montferrat (possibly, “Mongol Tartar”) was the leader of the Fourth Crusade, allegedly in the early XIII century, a Marquis and King of Thessalonica (1204-1207) – see [729], page 167; also [136], page 291. Therefore, we are likely to be confronted with linguistic relics testifying to the Mongol and Tartar leadership of the XIII century Constantinople campaign.

Another crusader knight bore the name of “Godfroi de Toron – a feudal ruler in the Kingdom of Jerusalem” ([729], page 168). His name, GOT-TR de TRN may also be derived from the word “Goth” (“Trojan”, “Frank” or “Turk”).

These facts are in good correspondence with our reconstruction, according to which the Russians took part in the conquest of Czar-Grad together with the Ottomans, or Atamans. Actually, historians do not dispute the fact that the Russians assaulted Constantinople, but they date these assaults to earlier epochs.

One must be aware of the fact that the surviving chronicles of Robert de Clary and Geoffroi de Villehardouin must be edited versions of a later origin dating from the XVII-XVIII century.

14. Direct participation of the Russian troops in the conquest of Constantinople.

As we have mentioned earlier, the Ottomans, or Atamans must have conquered Czar-Grad together with the Russians. Romanovian historians took special care to erase this fact from the history of the XIV-XV century. However, some reports of this event were fortunate enough to survive as duplicates, which were moved backward in time (to the IX-X century). The “editors of Russian history” did not recognize them for what they were; duplicates are doubtlessly useful that way.

Georgiy the Victorious, or Genghis-Khan, became reflected in Russian history as Ryurik, qv in CHRON4. Shifted backwards in time, he ended up in the phantom IX century A. D. (approximately, the years 862-879 according to [500], Volume 1, page 376) under the name of Ryurik.

We must therefore expect to find some information about the conquest of Czar-Grad by the Russians in the IX or the X century A. D. of the Scaligerian and Romanovian timeline. Indeed, Scaligerian history reports that several years before the ascension of Ryurik to the throne in the alleged year 860 A. D., Russian troops attack Constantinople under the leadership of Askold and Dir, the “Varangians”.

“In the reign of Michael III, Emperor of Greece . . . the new enemy of the empire came to the walls of Constantinople – the Scythian nation of the Russians, on two hundred vessels. They wreaked devastation upon all the land around the city with great cruelty, robbing the neighbouring islands and monasteries, killing everyone and inciting horror in the hearts of the capital dwellers” ([500], Volume 1, page 196).

According to this duplicate version, the Russians eventually withdrew.

The traditional legend of the Russian march to Czar-Grad led by the Great Prince Igor is also a phantom reflection of the events of the XIII-XV century. Here the campaign of the XIII-XIV century was chronologically shifted to the X century A. D. ([500], page 199). The Byzantine campaign of Prince Oleg, which is said to have taken place in 907 A. D., must be yet another phantom of this kind.

15. History of firearms: is our perception correct?

According to A. M. Petrov, “we are thoroughly confused about the history of firearms in Asia. For some reason, the prevailing absurd notion is that the Europeans introduced firearms to the Orient when their ships reached the Indian Ocean – after the epoch of the Great Discoveries, that is. The actual history was completely different.

In 1498 Vasco da Gama circumnavigated the Cape of Good Hope and sailed into the Indian Ocean. In 1511 the Portuguese started the siege of Malacca, one of the largest centres of sea trade in Asia. Much to their surprise, their cannon fire was answered by Malaccan artillery . . . After the capture of the city, the Portuguese found more than three thousand small cannons there” ([653], page 86).

“Timur managed to make some use of firearms in a number of battles (he died in 1405). Another known fact is the use of an enormous 19-tonne cannon by the Turks during the 1453 siege of Constantinople” ([653], page 87).

The founder of the Great Mogul Empire, Babur, “is meticulous to record every single detail that concerns firearms in his ‘Notes’. The first record was made in Central Asia, in 1495-1496 . . . It reports a successful shelling of a tower from cannons, which had made a hole in it . . . The records of 1526-1527 describe the whole process of casting a large weapon and its tests as carried out by the Turkic weapon armourers . . . Babur has made a multitude of such records about mortars, rifles, cannons and their manufacture by Turkic and other Oriental armourers without any assistance from Europe” ([653], page 87).

Therefore, the traditional opinion that firearms were manufactured in the West exclusively and then brought to the Orient by the Europeans is wrong. It appears to have been planted in the XVII-XVIII century as part of the disinformation campaign aimed at presenting the East as savage and the West as civilised.

16. Did the Horde conquer Transcaucasia or the Western Europe?

The data concerning the real directions of the campaigns launched by the Great Princes of Russia, or the Horde, are most contradictory as rendered in Romanovian history. For example, N. M. Karamzin reports that “our princes conquered the Yass city of Dedyakov (in South Dagestan), burnt it to the ground and returned with great spoils and many captives, making the Khan rejoice greatly and grace them with great praise and lavish gifts” ([362], Volume 4, Chapter 5, column 80).

However, N. M. Karamzin’s opinion that the campaign was directed at South Dagestan contradicts the indication of Prince M. Shcherbatov, who wrote that Russian chroniclers used the term Yass for referring to the inhabitants of the South-East Lithuania. He believed that the Russian troops really captured some Polish city in Upper Prut region. M. Shcherbatov was following Degin, a foreign historian. V. N. Tatishchev opined that the target of this campaign lay beyond the Dniester (see [362], notes to Volume 4, Chapter 5, column 58).

The “Arkhangelogorodskiy Letopisets” insists that the abovementioned city of Dedyakov (or Tetyakov) is located in Karelia ([362], notes to Volume 4, Chapter 5, column 59).

This example clearly demonstrates to us an enormous range of opinions in re the location of the city of Dedyakov as captured by the Russian knights during a “Mongolian” = Great campaign. The suggested versions include South Dagestan, Karelia, Poland, Lithuania and the lands beyond the Dniester. It is easy to explain such variety of opinions – Romanovian historians were doing all they could to conceal or destroy the descriptions of the Horde’s Western campaigns, which had resulted in the colonization of the Western Europe. Romanovian historians tried their hardest to make the Western campaigns look like local Russian events.

17. The toponymy of Stockholm, the capital of Sweden.

Pre-XVII century Russian sources transcribe the name of the Swedish capital as Stekolna ([578], Book 2, page 451). It is an obvious derivative from the Russian word for “glass”, steklo. This goes to say that the city in question was renowned for glass production – serving the needs of the Imperial court of Moscow and the Empire in general. The name Stekolna must have been transformed into Stockholm by the local authorities after the break-up of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire in order to make everyone forget that it was once part of the Russian Empire, or the Horde.

18. The reason why the famous icon of Our Lady of Kykkos from Cyprus is still concealed from public sight.

The present section is based on the materials and observations of our readers who visited the Cyprus Kykkos Monastery in 1998 and discovered a number of interesting facts that they reported to us. These facts can be explained by our reconstruction.

The Kykkos Monastery in Cyprus is quite famous. Its full name is as follows: “The Holy, Royal and Stauropegial Monastery of Our Lady of Kykkos” ([410], page 8). The monastery is believed to have been founded in the late XI – early XII century at the direct order of Alexis Comnene, Emperor of Byzantium (or the epoch of Jesus Christ, 1152-1185, according to our reconstruction). “The centrepiece of the Kykkos Monastery is the epoch of Our Lady, which, as tradition has it, was painted by Apostle Luke directly from the Holy Mother of God . . . In 1576 the icon was set in a silver and golden encasement; the new encasement was made in 1795. Her face is covered, and remains concealed always” ([410], page 9).

Let us enquire about the reason why the face of Our Lady on the icon is never revealed. The explanation provided in [410] does not answer this question: “It was either done at the request of Emperor Alexis, or in order to make the icon incite greater reverence” ([410], page 9). However, it is obvious that the icon was revealed – for the manufacture of the encasements in 1576 and 1795, at least. No encasement can be made without seeing the icon. Let us also remind the readers that such encasements usually have slots for faces. Apart from that, it is known that “in 1669 Gerasimos, Patriarch of Alexandria, dared to lift the cover in order to see the face of Our Lady, but was punished for his sacrilege and had to beg God for forgiveness with tears in his eyes” ([410], page 9).

We know the following of the church where the Icon is kept today: “The church was built for the specific purpose of housing the Holy Icon. It was built of wood initially, likewise the entire complex of the monastery . . . After the fire of 1541 the church was completely renovated, and the new constructions were made of stone . . . According to the inscription on the iconostasis, the latter was made in 1755, immediately after the fire of 1751” ([410], pages 12-13). It is believed that the archives of the monastery perished in the fires of 1751 and 1813. As we are being told today, these fires “destroyed the fruits of holy labours and works of art collected for centuries, rendering important manuscripts and historical documents to ashes” ([410], page 13). We are of the opinion that the fires had nothing to do with it. The matter is that the territory in question was taken away from the Turks in the late XVIII – early XIX century, and countless Scaligerites came here from Europe. The Greek Revolution took place in 1821. It turns out that the Archbishop of Cyprus and three Metropolitans were executed by handing that very year ([410], page 24). Therefore, the identity of the party responsible for the incineration of the Kykkos monastery may well be disputed, as well as whether the valuable archives of the monastery really perished because of the blaze. It is more likely that they contained a large number of documents that could shed some light on the true history of the XV-XVI century. Could it be mere coincidence that all the documents were destroyed just when the Europeans finally got access to Cyprus?

We must note that the new encasement for the icon was made in 1795, and the new iconostasis – in 1755 ([410], pages 9 and 13). The monastery archives were destroyed by the fires of 1751 and 1813. All these events must have occurred around the same time, just before the Greek revolution. One gets the natural idea that the archives of the monastery were destroyed during the revolution, and the fire legend was invented a posteriori. Could the icon have been covered up just then, or even later, at the end of the XIX century? This could be a result of liberation from the “Turkish yoke” and the corresponding change of the official viewpoint on the “ancient” and mediaeval history. The icon of Our Lady of Kykkos must have been open to the worshippers until the XVII, or maybe even the XIX century. The very idea to conceal the face of an icon, and not just any old icon, but one painted by Apostle Luke himself, seems very odd and has no analogies.

What could have offended the editors of mediaeval and “ancient” history so much that they had to conceal the icon from public sight forever?

We cannot provide a definitive answer to this question, since we know of no veracious copies of the icon. Moreover, according to Archbishop Sergiy in his fundamental work entitled “The Complete Oriental Menaion” ([39]), the famous XIX century book under the title of “Icons of Our Lady” contains a false representation of this icon ([39], Volume 2, page 394). One must also note that the Holy Feast of this famous icon falls over 26 December (Old Style), the next day after Christmas, that is. This day is officially called “The Holy Feast of Our Lady’s Church” ([39], Volume 2, page 393).

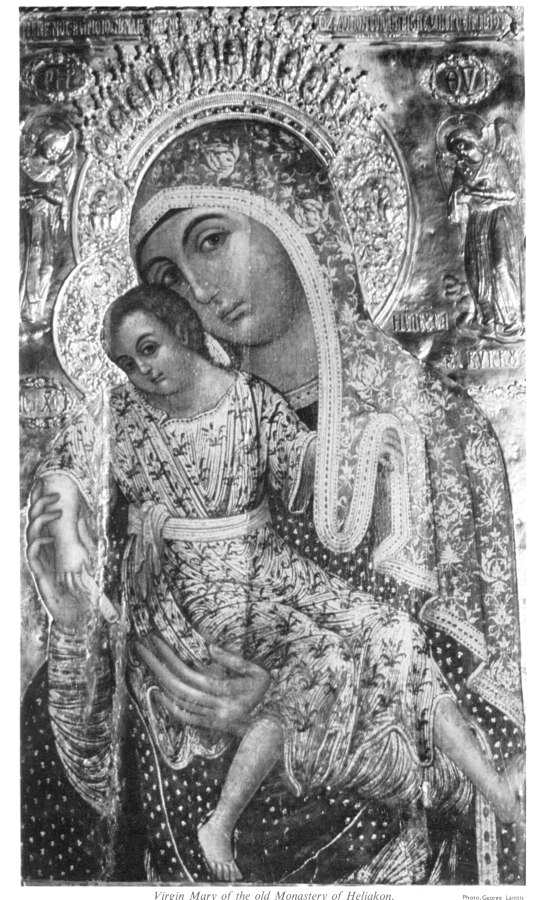

Nowadays the visitors to the Kykkos Monastery can only see the icon as it is represented in fig. 12.43. The face of Our Lady is covered; the slot in the cover only reveals the encasement. The icon is therefore completely hidden from sight. The encasement is new, made in 1795, qv above. The old encasement of 1576 can be seen in the actual Church of the Kykkos Monastery ([997], page 25; see fig. 12.44). The old encasement houses another icon of Our Lady ([997], page 35; see fig. 12.45). Therefore, nowadays we can only see the old XVI century encasement with a different icon inside, and not the authentic icon painted by Apostle Luke.

Let us pay attention to the headdress of Our Lady as copied by the old encasement of 1576 (figs. 12.44 and 12.45). What we see is a typical Russian kokoshnik headdress. Many icons portray Our Lady wearing a crown; however, we see a traditional Russian headdress in this one. Could the very name of Kykkos be a derivative from the Russian word kokoshnik? Especially considering that “the toponymy of the name Kykkos is unknown. According to one of the more plausible versions, it can be traced to the ‘kokkos’ shrubs growing in these parts” ([410], page 8). However, due to the frequent flexion of the sounds S and SH in the ancient texts, the Russian word kokoshnik could have easily transformed into the “Greek” word kokkos, hence the name Kykkos. The obvious guess is that the famous Our Lady of Kykkos is “Our Lady in a Kokoshnik”.

Moreover, there is the Russian word kika, which stands for a variety of a kokoshnik with an enlarged front ([223], Volume 2, page 267).

It could be that the sight of Our Lady wearing a Russian kokoshnik infuriated the Scaligerite scientists of the XVII century so much that they had to cover up the icon. However, a trace of this headdress survived in the name of the icon and upon the old encasement of 1596. It is possible that the actual icon, if we could see it, depicts the kokoshnik even more explicitly. Moreover, we have come up with many other questions that are quite as interesting. For instance, why does the old encasement leave most of Our Lady open, qv in figs. 12.44 and 12.45, whereas the new one covers the icon up completely, inasmuch as the cover reveals (fig. 12.43)? Could there be other interesting details present, apart from the Russian kokoshnik headdress, such as lettering, symbols on the clothing and so on? It would be very interesting indeed to take a look at the old icon – if it has at all survived, that is. Could it be that the visitors are shown the new encasement and the modern cover upon it, and nothing but?