Part 4.

Western European archaeology confirms our reconstruction, likewise mediaeval cartography and geography.

Chapter 14.

The real contents of Marco Polo's famous book.

1. Introduction. The identity of Marco Polo.

What does Marco Polo’s famous book describe in reality? The readers might already wearily reply: “ancient Russia once again”. Let us correct – not merely Russia as actually described by Marco Polo under the names of Tartary, India and China, but also several other European and Asian countries. The ones that weren’t described are the modern India and China, which Marco Polo is believed to have visited today.

As we shall demonstrate, the initial text of Marco Polo, really created in the XIV-XVI century, was describing the Great = “Mongolian” Empire, or the mediaeval Russia.

However, when the Portuguese and the Western Europeans of the XVII-XVIII century in general finally circumnavigated the coast of Africa and ended up in the South-East Asia – independently from the fleet of the Horde and the Atamans, the country they discovered, or the modern India, was mistaken for the India of Marco Polo that they were searching. The seafarers had already forgotten the authentic history of the XIV-XVI century, and were accustomed to the Scaligerian geography of the XVII-XVIII century, where the old name “India” as used by the Horde already referred to the territory of the modern India, and not the rest of the Horde.

When the travellers returned to Western Europe, they included all the exotic things that fascinated them (the elephants, the apes, the cannibals etc) into all of the later editions of Marco Polo’s book, so as not to conceal new and intriguing data about “the famed distant India” from the reader. Apparently, the inclusion of new information into an old book, with the name of the author remaining intact, was typical for that epoch.

As a result, the contents of Marco Polo’s book as we know it today are a mixture of his own description of “Mongolia”, or Russia in the XIV-XVI century and newer Western European data pertaining to the “authentic” modern India, brought to Europe by European seafarers in the XVII-XVIII century.

This is how the Muscovite Russians, or “Tartars and Mongols” wearing the kaftans of marksmen ended up side by side with the naked tropical cannibals. Editors of the XVII-XVIII century simply failed to see a contradiction here. Nowadays commentators writing in good faith are greatly confused since they do not understand how a single page of Marco Polo’s book can contain obvious references to the Russian marksmen and descriptions of horrifying crocodiles and herds of elephants.

We shall be using the fundamental academic edition of Marco Polo’s book ([1264]), complemented with detailed comments.

Marco Polo (allegedly of 1254-1324 A. D.) is considered the greatest traveller of the XIII century, hailing from Venice in Italy. He undertook a long journey and travelled for several years, allegedly in 1271-1295, visiting a number of distant lands; among them – Tartary, the kingdom of the Great Khan, and then presumably India, China, Madagascar, Ceylon and Africa. Moreover, it is presumed that he was the one to introduce the very word “India” into the vocabulary of the West Europeans ([797], page 488). It stands for “a distant land”, as we already know.

His standard biography is as follows: “Polo, Marco, ca. 1254-1324, Italian traveller. In 1271-1275 he travelled to China and stayed there for some 17 years. In 1292-1295 he made his way back to Italy by sea. His ‘Travels’ (1298) rank among the earliest sources of knowledge about the lands of the Central, Eastern and Southern Asia that the Europeans had” ([797], page 1029).

However, despite his fame that is said to have thundered all across Europe ever since the XIII, the first interest in the biography of Marco Polo was expressed as late as in the XVI century – three hundred years later, that is ([1078], Volume 1, page 2). “The first one to try and systematise the knowledge of Marco Polo’s life was his fellow countryman John Baptist Ramusio” ([1078], Volume 1, page 2). Actually, the name of this “biographer” translates as “John the Baptist of Rome”. Therefore, the biography of Marco Polo was covered in obscurity for three hundred years at least, presumably to regain its splendour only in the middle of the XVI century.

Marco Polo is said to have been buried in the Church of St. Lorenzo in Venice. However, there is no such grave in St. Lorenzo, and no such grave has ever existed there ever since the end of the XVI century at least ([1078], Volume 1, page 74). Even if there was such a grave here at some point, the data that we learn from [1264] imply that it was destroyed in 1592 during the reconstruction of the church. Why would the Venetians treat their famous compatriot so unjustly? Apparently, no such grave has ever existed here.

Further on, [1264] reports that no authentic portraits of Marco Polo exist anywhere ([1078], Volume 1, page 75). Marco Polo is believed to have hailed from a highly distinguished family that vanished completely in the early XV century ([1078], Volume 1, page 8).

And so, in the XVI century, which is when the biographers first expressed an interested in the life of Marco Polo, they could find no traces of him anywhere in Venice.

On the other hand, the following oddity is to be considered: the first printed edition of Marco Polo’s book appeared in the alleged year 1447 – in Germany, and written in German ([1264], Volume 2, page 554). Why didn’t it come out in Italy and in Italian?

In the first page of the German edition we see a portrait of Marco Polo accompanied by the following legend: “Das ist der edel Ritter. Marcho polo von Venedig . . .” (see fig. 14.1). The literal translation is as follows: “This is the noble knight Marco, the Venetian Pole”. Why do we translate the word “polo” as “Pole”? But how are we supposed to translate it? It begins with a lowercase “p”, whereas all the actual names begin with a capital (“Marco”, “Venice” and so on). Hence the obvious consideration that the word “polo” stands for “Pole”.

Our opponents might counter saying that the Italian city of Venice is mentioned here as well. As a matter of fact, the exact translation of “Venedig” might be different – apart from Venice in Italy, it may have stood for the famous Venedia, or Wendia – the famed Western European Slavic region ([797], page 207). In our age the Western Slavs are known as Poles in particular. Therefore, the first German edition of Marco Polo’s biography appears to consider him a Pole from Venedia – hence “Marco the Pole”.

2. Who was the real author of Marco Polo’s book?

It is commonly known that the book of Marco Polo wasn’t written by himself – he is believed to have dictated it to someone (see above and in [797], page 1029). Marco Polo is referred to in the third person throughout the book. For example, Chapter 35 of Book 2 begins as follows: “It must be known that the Emperor had sent the abovementioned noble Marco Polo, the author of this whole story, on a journey . . . And now I shall tell you what he [Marco Polo – Auth.] saw in his travels” ([1264], Volume 2, page 3).

This fact was obviously pointed out by the commentators of [1264] – we aren’t revealing anything new here.

Furthermore, it turns out that the book of Marco Polo has reached us processed by a professional novelist known as Rusticiano. According to the commentator Henry Cordier, “one cannot help wondering about the extent . . . to which Polo’s text was transformed by Rusticiano, a professional writer” ([1078], page 112). The intrusions of Rusticiano into the original text, if it had at all existed, can be traced throughout the entire book ([1078], page 113).

We have therefore got every reason to suspect that the text of Marco Polo as known to us today is a novel of the XVII-XVIII century and not a collection of travel notes.

3. In what language did Marco Polo read or dictate his book?

The question isn’t ours, and we do hope the readers appreciate the formulation. It turns out that we don’t even know what language Marco Polo’s book was written in.

The following is reported: “As for the language that Marco Polo’s book was written in originally, there are different opinions. Ramusio thought it was Latin, without any particular reason; Marsden suggested it was the Venetian dialect, and Baldelli Boni was the first to demonstrate . . . that it had been French” ([1078], page 81). However, the dispute continues to date.

This clearly implies that the original of Marko Polo’s book isn’t merely nonexistent – we don’t even know what language it was in; we have nothing at our disposal but later manuscripts and publications in a variety of languages.

4. Did Marco Polo visit the territory of modern China at all?

4.1. The location of the Great Wall of China.

Serious doubts about whether Marco Polo actually visited the territory of modern China accompany a critically minded reader throughout the entire book. Even the traditionalist commentators express their doubts. The cup of their otherwise endless patience ran over due to the circumstance that Marco Polo never got to sample Chinese tea, and, on top of everything, didn’t notice the Great Wall, which is extremely odd, since he’s believed to have lived in China for seventeen years, qv in [797], page 1029. How could it be? Did no one ever mention it to him? Didn’t it ever surface in conversation as a local “wonder”?

The puzzled commentator tells us simply: “He doesn’t utter a single word about the Great Wall of China” ([1264], Volume 1, page 292). Certain puzzled scientists have even tried to discover “implicit references” to the Great Wall in Marco Polo’s text, the assumption being that he was aware of the Wall’s existence, but had certain ulterior motives for writing nothing about it. Modern scientists are trying to fathom the nature of these motives. Yet Marco Polo’s awareness of the wall’s existence is never questioned ([1078], page 110).

4.2. How about the tea?

Let us consider tea. The evasive modern commentary is as follows: “It is strange that Polo never mentions the use of tea in China, despite the fact that he travelled through the tea region of Fu Kien; after all, during that epoch the Chinese drank tea just as frequently as they do today” ([1078], page 111).

Such pity about the tea. Seventeen years spent in China, and not a single cup of the famous Chinese tea. What did he drink in the mornings, after all?

The notion that Marco Polo “never travelled anywhere and invented everything” is very common, and has proponents in the ranks of the academia to this very day. This is, for instance, what the “Kommersant Daily” newspaper wrote on 28 October 1995:

“Marco Polo didn’t like tea.

Frances Wood, Director of the British Library’s Chinese Department defends the opinion that she arrived at as a result of her research concerning the hypothetical visit of Marco Polo to China on the pages of the Times, expressing her doubts about whether the famous Venetian had really visited the Chinese Empire. The researcher is of the opinion that he didn’t get any further than Constantinople, subsequently going into hiding somewhere in the environs of Genoa to write down the story of his fictitious travels: ‘Polo’s book doesn’t say a word about either the Great Wall, tea, china or the deformed feet of the women – he couldn’t possibly have failed to notice all of it’. Her opponents assume that such indifference to tea can be explained by the fact that travellers prefer stronger drinks”.

Opponents appear to have no other answer, and therefore try to render the problem to a joke. We feel obliged to repeat our question: what if Marco Polo didn’t deceive anyone, but simply visited a different country?

4.3. Has Marco Polo seen Chinese women?

There is a famous and unique custom that concerns Chinese women, which has been noticed by every European to visit the territory of the modern China. This custom had existed until very recently. Ever since their childhood, Chinese women wore special shoes that didn’t let their feet grow in the natural manner. This is how their feet were made unnaturally small, which was considered seemly, but intervened with freedom of motion – for instance, Chinese women couldn’t run. At any rate, this trait is very characteristic, and couldn’t have been let unnoticed by any traveller. How about Marco Polo? Not a word, although he is said to have spent seventeen years in China. The astonished commentator of [1264] obviously points out this fact, and remains confused ([1078], page 111).

4.4. Where are the hieroglyphs?

Marco Polo doesn’t say a word about the famous Chinese hieroglyphic writing ([1078], page 111). No commentary is needed here.

4.5. What else did Marco Polo “ignore” about China?

According to the clueless remarks of the commentator of [1078], Marco Polo has also “ignored” the following:

a) book-printing in China,

b) the famous Chinese hatching units for artificial poultry raising.

c) the “big cormorant” fishing technique,

d) “as well as a variety of other remarkable arts and customs that it would be natural to remember” for a traveller in China ([1078], page 111).

The commentator summarises: “It is hard to explain all these omissions of Marco Polo [in reference to China – Auth.], especially if we’re to compare them to his more or less detailed descriptions of Tartar and South Indian customs. One gets the impression that he had communicated with foreigners for the most part while in China [sic! – Auth.]” ([1078], page 111).

4.6. What “indubitably Chinese phenomena” did Marco Polo notice during his visit to “China”?

Our answer shall be very brief: nothing at all! It is easy enough to notice by his book ([1264]).

5. Geographical names used by Marco Polo were considered his own inventions in Europe for two hundred years.

The first biographer of Marco Polo, modestly named John the Baptist of Rome (John Baptist Ramusio), who lived in Venice in the middle of the alleged XVI century writes the following in his preface to Marco Polo’s book:

“His book, which contains numerous errors and inaccuracies, was considered fantasy for many years; the dominant opinion was that the names of towns and cities contained therein [all names! – Auth.] had been invented by the author, with no real basis underneath – pure fiction, in other words” ([1264], Volume 2, page 2).

The publisher has repeated it four times here that the geography of Marco Polo was fiction through and through. But how close is that to the truth? Could Marco Polo have visited other places?

6. What are the “islands” mentioned by Marco Polo?

Mediaeval travellers, including Marco Polo, often refer to countries as to islands. We have cited many such examples in CHRON4 – for instance, even Russia was occasionally called “island”. In CHRON4, Chapter 18:5 we have already explained that the world “island” was formerly used for referring to a land or a country in Asia, or in the Orient. The English word “island” was derived from “Asian land”.

In the Middle Ages, “all the faraway lands that needed to be reached by sea were called islands” ([473], page 245).

Sometimes such “explanations” are so dubious that the modern commentators are forced to write such things as “Polo describes Ormus as though it were located on an island, which contradicts . . . reality” ([1078], pages 97-98).

Therefore, when we discover references to islands in Marco Polo’s book, we shouldn’t think that he really refers to islands in the modern meaning of the word – most likely, countries.

7. Why modern commentators have to “correct” certain names used by Marco Polo, allegedly in error.

Having fallaciously “superimposed” the book of Marco Polo over the territory of the modern China, historians were amazed to discover that the names used by Marco Polo didn’t look Chinese at all, for some odd reason. Then they started to correct Marco Polo in the following manner.

Polo often uses several spellings of a single name, often at close distance from one another ([1078], page 84). Commentators try to choose the ones that sound “the most Chinese”, writing such things as “in two or three cases I suggested a spelling that isn’t present in any of the sources” ([1078], page 143).

Here are a few examples. “Correct Oriental forms of the names Bulughan and Kukachin have transformed in a number of manuscripts . . . into Bolgara [or Volgara! – Auth.] and Cogatra . . . Kaikhatu Kaan figures as . . . Chiato and . . . Acatu” ([1078], pages 85-86).

The names don’t really sound Chinese. One might suggest a variety of hypotheses in order to reconstruct their real meaning, such as:

The name Bolgara refers to the region of River Volga.

The name Acatu is the well-known Russian name Asaf (or Iosaf), considering the frequent flexion of F and T.

The name Chiato (Chet) is familiar to us from Russian history, and was borne by the founder of the famous Godunov family, an ancestor of Czar Boris “Godunov”, qv in CHRON4. And so on, and so forth.

Let us cite another example. In Chapter 10 of Book 3 Marco Polo tells us about the lands of Samara and Dagroian, or the Kingdom of the Dagi ([1264], Volume 2, page 292).

However, the table that we have compiled from the materials of V. I. Matouzova ([517], pages 261 and 264) makes it clear that the Dagi was the name of the Russians (as used in mediaeval England, for instance, qv in CHRON4, Chapter 15:1.5). Therefore, the Kingdom of the Dagi identifies as the Russian Kingdom. Below we shall give an explanation of what Russian customs could have given birth to the moniker “Dagi”.

Let us carry on. We hardly need to remind the reader that Samara is a famous Russian city on the Volga, or, alternatively, Sarmatia – Russia, or Scythia, in other words. In CHRON4 we already mentioned that Samara must have been one of the old capitals of the Golden Horde, possibly also the Samarqand of Timur. Indeed, some manuscripts of Marco Polo’s book use the name “Samarcha” for referring to Samara ([1264], Volume 2, page 294). Could that be “Samarqand”? The actual name “Samarqand” must have stood for “Sarmatian Khandom” – Sarma-Kand or Sarma-Khan.

Incidentally, when Marco Polo describes Samara he makes a reference to the “abundance of fish in these parts, which is the best in the world” ([1264], Volume 2, page 292). This is coming from a Venetian who should know something about fish. Could it be the Volga sturgeon that Marco Polo enjoyed so much?

Needless to say, historians have neither found Samara, nor Dagroian in the South-Eastern Asia. What did they suggest as a replacement? Sumatra instead of Samara, and the formidable name Ting-Ho-Rh instead of Dagroian ([1264], Volume 2, pages 296-297).

Therefore, the word “Samara” must have stood for “Sarmatia” in Marco Polo’s book – Scythia, or Russia, that is.

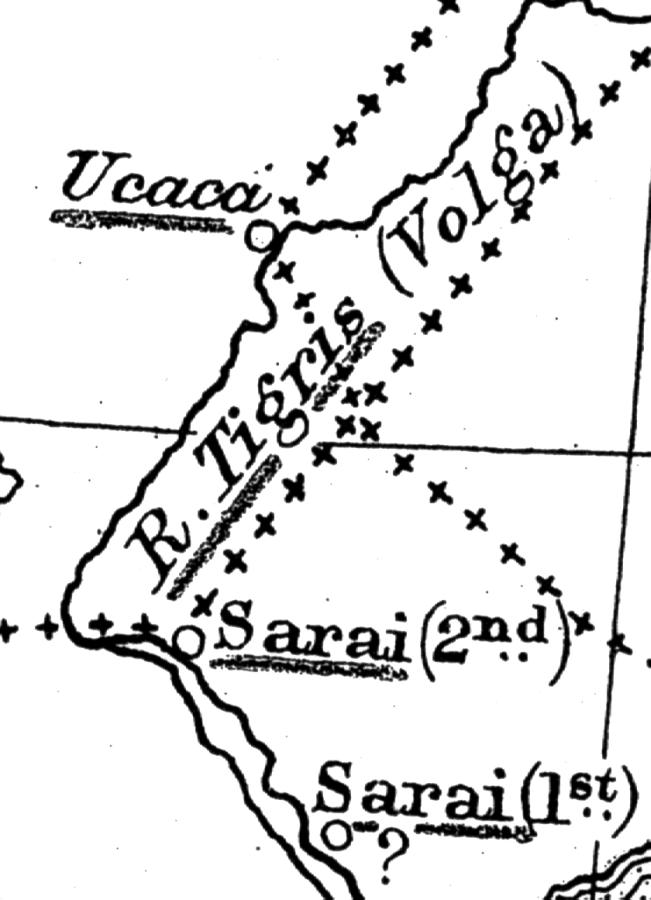

Where did Marco Polo travel, after all? For instance, we know that Polo the Elder voyaged along Tigris, which is localised in Mesopotamia today – apparently, erroneously so, since modern commentators report that some of the mediaeval travellers believed Tigris to identify as River Volga. Polo the Elder, for instant, used the name “Tigris” for referring to Volga – see the map entitled “Marco Polo’s Itineraries. No. 1” in [1264], Volume 1. The map tells us explicitly: “R. TIGRIS (VOLGA)”. See figs. 14.2 and 14.3.

And so, where did the mediaeval West Europeans localise the famous Mesopotamian River? Apparently, in mediaeval Russia (or India), a land that lays at a considerable distance from the Western Europe (India - from the Russian word “inde”, “far away”). There are many large rivers in Russia – the areas between them could be called “Mesopotamia”, or “interfluve”.

We believe the explanation to be simple. Up until the moment when the Scaligerite editors of the XVII century rearranged the maps, ascribing the names “India” and “China” exclusively to the territories known as such today, West Europeans must have used the words “India”, “China” and “Mesopotamia” for referring to a single country – Slavic and Turkic Russia, or the Horde = Scythia of the XIV-XVI century.

8. What direction should one take in order to reach India and China from Italy?

The question will instantly be answered: Southeast, or East at the very least – not Northeast, and certainly not North. It suffices to take a look at the map.

However, the first biographer of Marco Polo cherished the naïve conviction (allegedly in the middle of the XVI century) that Polo’s route lay to the North and Northeast from Italy ([1078], page 2). Moreover, he was of the opinion that Marco Polo travelled some lands to the North of the Caspian Sea – Russia, in other words.

His text is as follows: “Ptolemy, as the last of the [ancient] geographers, was the most knowledgeable [of them all]. His knowledge of the North comprised all the lands until the Caspian Sea . . . His knowledge of the South ended beyond the equator. These unknown regions in the South were first discovered by the Portuguese captains of our time [the XVI century the earliest – Auth.]. As for the North and the Northeast, these lands were discovered by the brilliant nobleman Marco Polo” ([1078], page 2).

Let us consider this text, which is presumed to date from the XVI century, once again and more attentively. It clearly indicates that Marco Polo travelled to the North or the Northeast of the Caspian Sea – along the Volga, or between the Volga and the Ural, in other words. The lands found to the North of the Caspian have always belonged to Russia.

Therefore, Marco Polo travelled through Russia

9. Why Marco Polo mentions spices, silks and oriental wares in general when he tells us about India, or Russia.

Our opponents might want to enquire about the following matter. If Marco Polo’s India was really Russia, whence the references to spices, silks, apes and so on. There are no wild apes in Russia, and no spices grow there.

This is correct. However, one could encounter all of the above sold for a profit – for instance, at the famous Yaroslavl (or Novgorod) marketplace in the Mologa estuary. Spices and other exotic wares were brought here from the Orient – India in the modern meaning of the word, Persia and so on. No Western European merchants ventured further than the Yaroslavl Market.

Indeed, they couldn’t have travelled any further. We have already explained how the trade between the East and the West must have been organised in the XIV-XVI century – with Russia acting as an intermediary. Being in control of vast territories, the Great = “Mongolian” Empire chose a very clever tactic indeed. The flow of wares from the West and the East converged in a single point – the Yaroslavl Market, or the Azov region of the Don. Customs offices were located here, and they collected tax. Therefore, Western traders weren’t allowed any further than the market, likewise the Eastern traders – in order to make all of them pay the Russian tax.

10. The toponymy of the name “India”.

And so, the Westerners would find Oriental wares in Russia. Deeply impressed by the cute little monkeys and the abundance of ginger, they enquired about their land of origin. Russian traders replied “from indea”, which translates as “from a distant land”, weighing the cinnamon and charging their clients hefty sums in full knowledge that they couldn’t buy exotic goods at any other market.

This is how the trade was done in the epoch of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire, which covers some three hundred years. The Westerners were obviously doing their utmost in order to find a diversion so as to pay less for their purchases.

The original meaning of the Russian word “India” (formerly “Indea”, cf. “inde” – “elsewhere”, “somewhere”, “on the other side”, qv in [786], Issue 6, page 235) may not be understood by everyone – it had simply stood for “a distant land”, “a foreign country” etc.

The adverb “inde” is no longer used in Russian. However, it was adopted by the Latin language, which was created in the XV-XVI century, without even changing its form. Nowadays it can be found in any Latin dictionary, meaning “thence, from that place . . .” ([237], page 523). The traders, who were beginning to speak Latin, brought this word back from the Yaroslavl (Novgorod) market, as well as the name “India” (faraway land), which is derived from it.

Incidentally, the Russian “Voyage” of Afanasiy Nikitin uses the word “India” in this very meaning, in general reference to distant lands.

11. When and how were certain geographical names used by Marco Polo “localised”.

Polo’s first biographer wrote the following in the middle of the alleged XVI century: “However, over the last few centuries the people familiar with Persia started to think about the existence of China [?! – Auth.]” ([1078], page 3).

Let us remind the readers that at some point in the past, the Westerners were “aware of China’s existence” - as Scythia, or the ancient Russia; see Part 6 of the present book, which uses materials taken from Scandinavian chronicles in order to prove that in the XIV-XVI century “China” was the name of Scythia. Then, in the XVII century, it was “lost”, together with the knowledge that the name China referred to Russia, or “Mongolia”, in the days of yore. For some period of time, the West Europeans were convinced that there was no China at all, and that all of Marco Polo’s accounts of his voyage to China were pure figments of imagination ([1078], page 2).

In the XVII-XVIII century, when the Westerners finally reached the Orient independently by sea and discovered the new lands that they had not been familiar with previously, they recollected the “lost China” and decided to look for it, eventually locating the country in the Far East. However, they weren’t aware of the fact that they only managed to discover the easternmost and relatively small part of the former China, or Scythia, or the Great = “Mongolian” Empire.

It must have happened as follows. Upon arriving to South-East Asia with Marco Polo’s book in their hands, Europeans of the XVII-XVIII century started to search for names familiar from Marco Polo’s book. Why would they need to do it? The answer is quite simple. Let us step in the shoes of the Portuguese captain of the XVII-XVIII century, whose journey was driven by practical considerations, not abstract scientific interest, and sponsored by the king. This captain had a clear objective of finding a trade route to India and also China, which was somewhere near India, according to Polo.

The captain in question couldn’t have returned without “finding” China and other countries from Polo’s book. In order to prove it to the king that the correct route to India and China was indeed discovered, the captain was simply obliged to find some names familiar from Polo’s book on the terrain at least, seeing as how it was the only source of knowledge about India and China ([797], page 488). Obviously enough, the captain could not report that his mission was a failure for fear of losing his job.

And so, when the Europeans finally reached the South-East Asia, they started their search for the names from Polo’s book. However, everyone they met spoke a foreign language, completely beyond their comprehension and based on altogether different phonetic principles. The names were also local, and therefore incomprehensible.

It is very hard for any European to make head or tail of the local names due to the complexity of the local phonetics. Therefore, European travellers wrote the well familiar names from Polo’s book on the maps of the South-East Asia that they compiled – earnestly and in good faith, without any intentions of deceit, under the erroneous assumption that they were reconstructing the old names of these places from Polo’s book. They must have looked for phonetic matches and rejoiced if they could find any; however, most often this wasn’t the case and they simply used the names they found in the book of Marco Polo.

Europeans “found” Samara, Java, Ceylon, Madagascar etc in South-East Asia, following the indications of Marco Polo and using his names for the newly discovered (in the post-Imperial epoch) islands and countries in the remote Southeast. However, the actual descriptions of these “islands” as given by Marco Polo give no reason for such unambiguous identifications.

Let us just cite a single edifying example out of a great many similar ones. Let us open the Encyclopaedic Dictionary ([797]) and read what is said about the Indo-Chinese Isle of Java. We quote:

“An island in the Malayan archipelago, Indonesian territory. Length: over 1000 km, area: 126.5 square kilometres. Population: circa 83 million (1975). Over 100 volcanoes (about 30 of them active; the tallest is 3676 metres), situated alongside the axis of the island, there are hills and valleys in the north. Frequent earthquakes. Deciduous and evergreen tropical forests, savannahs in the east. The plains are cultivated (rice, manioc, maize and yam). Main cities: Jakarta, Bandung and Surabaya” ([797], 1564). This is all that we learn about Java.

Here’s the description of “Isle Java” given by Marco Polo: “There are eight kingdoms there, and eight kings wearing crowns. The whole populace is pagan; each kingdom speaks a language of its own. There is an abundance of valuables on the island, expensive spices and aromatic oils . . .” ([1264], Volume 2, page 284). And so on, and so forth. Polo doesn’t report any typical geographical characteristics of the area – not a single word about volcanoes, tall mountains or names of cities.

One wonders why we are supposed to assume that Marco Polo’s Java is the very same Java that was baptised thus by the Western European captains of the XVII-XVIII century, with Marco Polo’s books in their hands? Such arbitrariness allows identifying any given place in any which way provided the locals don’t mind too much. Let us also point out a peculiar detail. Where did the Europeans manage to find Marco Polo’s names? On remote and wild islands inhabited by savage tribes in that epoch. The tribesmen were illiterate and did not oppose the “white gods from ships”, armed with cannons and making decisive statements in an unfamiliar language.

More civilised regions were more problematic – Manchurian China, for instance. In the XVII-XVIII century, the Chinese treated foreigners with great suspicion; in 1757 the Manchurians altogether forbade foreign trade in every harbour except for Canton ([151], Volume 5, page 314). The results are visible perfectly well. Apart from the city of Canton, and, possibly, two or three more cases, we cannot find any of Marco Polo’s names on the territory of the modern China.

Actually, the Chinese name of Canton is Guangzhou ([797], page 538). Do the two names have much in common? It would be expedient to remind the reader that “canton” is a French word that simply translates as “district”. Why drag the French word to the East of China and inscribe it on a map?

The matter is that Marco Polo knew French. Had it been English, we would have a city called Town in China – also very similar to Guangzhou, isn’t it?

Since the Europeans had failed to “discover” any of Marco Polo’s names in China, they invented the theory that Polo particularly detested the Chinese language. Modern commentators write the following in this respect: “One gets the impression that he [Polo – Auth.] was communicating with foreigners predominantly while in China. If any place that he describes had a Tartar of a Persian name, he would invariably use it in lieu of the Chinese version. Cathay, Cambaluc, Pulisanghin, Tangut, Chagannor, Saianfu, Kenjanfu, Tenduc etc – all of the above are Mongolian, Turkish or Persian versions, although they all possess Chinese equivalents” ([1078], page 111).

There is nothing odd about it. Marco Polo really didn’t know any Chinese due to the simple fact that he had never visited the territory of modern China. When the West Europeans came to China in the XVII-XVIII century, not really allowed deep into the country, they had to use second-hand data – Turkish, Persian etc (written down by travellers of those nations who visited inner parts of China). This is how the Turkish and Persian names used for referring to Chinese towns and cities may have appeared in later editions of Marco Polo’s book.