Part 4.

Western European archaeology confirms our reconstruction, likewise mediaeval cartography and geography.

Chapter 15.

The disappearing mystery of the Etruscans.

conquered a vast territory and founded numerous cities. They

created a mighty fleet and remained masters of seas for a long

time . . . having also attained great perfection in military

organisation . . . They discovered literacy, studied the science

of the gods with much diligence, and made great achievements in

their observation of the lightning. For this reason, they are

still of great interest to us . . .”

Diodorus of Sicily. XIV, 113. Quoting according to [574],

reverse of the cover.

1. The mighty, legendary and allegedly enigmatic Etruscans.

Scaligerian history retains the unsolved mystery of the Etruscans and their identity.

They are the nation that lived in Italy before the foundation of Rome in the alleged VIII century B. C., having left a legacy of highly evolved culture and then disappeared mysteriously, leaving numerous enigmatic artefacts behind. The latter are covered in a script that remains insoluble, although it is worked upon by generations and generations of scientists, who have invested an enormous amount of effort thereinto.

“Currently, many prominent researchers from a variety of universities are working on the mysteries of the perished world of the Etruscans . . . Ever since 1927, a magazine entitled ‘Stadi Etruschi’ has been coming out; it tells the reader all about their successes and problems [those of the Etruscan studies – Auth.] . . . One still cannot quite evade the impression that great efforts of whole generations of talented and hard-working scientists have made our entire body of knowledge only marginally greater, and only in the sense that now we see the Etruscan problem with much greater clarity, but not the actual Etruscan world. Out of many insoluble problems that have accumulated in every department of Etruscan studies, two are of particular importance and acuteness – the progeny of the Etruscans and their language” ([106], page 28).

However, our conception appears to offer a final solution to the “Etruscan enigma”. Apparently, as early as in the XIX century the scientists A. D. Chertkov and F. Volanskiy suggested a solution.

It became clear why the actual Etruscans called themselves “Rasenna” – “Racenes”, or “Russians” ([106], page 72).

However, their suggested solution of the Etruscan problem, despite the unambiguous interpretation of a number of Etruscan texts at least, contradicted the Scaligerian version of Chronology and history completely – in the spirit, for the most part.

This sufficed for the scientific community to distrust A. D. Chertkov and F. Volanskiy, although nobody has come up with anything in the way of counter-argumentation (at least, we have discovered none such in the research materials that were accessible to us). Obviously, there was indeed nothing to counter – A. D. Chertkov and F. Volanskiy have indeed managed to read a number of Etruscan writings at the very least.

This is precisely why the specialists in Etruscan studies have remained completely silent about the results of Chertkov’s and Volanskiy’s research for over a century.

Moreover, apparently in the absence of other means of countering Chertkov and Volanskiy, somebody started to parody them, straight-facedly publishing the results of “research” with allegedly similar, but obviously absurd “decipherments”. The replacement of one’s opponent’s arguments by similarly sounding absurdities (parody, in other words) is an unfair, but common method of “scientific opposition”.

This position is easy to understand. On the one hand, what can anyone say if certain Etruscan inscriptions can truly be read with the aid of Slavonic grammar. This can hardly be interpreted as a “chance occurrence”.

On the other hand, agreeing to such a hypothesis is also a non-option. If we are to admit that the Etruscans were of Slavic descent, the next assumption that we have to make is that they can be identified as the Russians.

So where are we at? Could the Russians have indeed founded the Italian Etruria, “the hearth of the most ancient culture in Italy and the eternal protector and benefactor of religions”, according to Cardinal Egidio from Viterbo ([106], page 4).

So what? Could the Russians have in fact inhabited Italy before the foundation of Rome? In the Scaligerian conception of history it makes no sense at all. However, the New Chronology makes the results of A. D. Chertkov and F. Volanskiy easy enough to understand.

Moreover, it would be very odd if the “Mongolian”, or Russian and Turkic, invasion hadn’t left any trace in the mediaeval Italy of the XIV-XVI century. Indeed, it is true that the Etruscan “Mongols”, or Great Ones came to Italy in the XIII-XIV century, prior to the foundation of Italian Rome in the XIV-XV century, qv in CHRON4.

There is much written about the presence of the Slavs in Italy. A couple of examples are as follows: “Ottocar [or the famous Odoacer – Auth.], King of the Rugian Slavs, took over the whole Kingdom of Italy . . . This city (Rome), presumably the capital of the world, didn’t suffer such a defeat from any other nation but the Slavs . . . Ottocar, also known as Odoacer, was a Rugian Slav . . . who had ruled the Italian kingdom for a whole of fifteen years” ([617], pages 90-91). The reference is most likely made to the famous Gothic War of the alleged VI century A. D. (and, according to CHRON1, the war that was fought in the XIII century A. D.). The implication is that Italy was conquered by the Slavs in the XIII-XIV century. Is it a wonder that Etruscan relics are still found in that area (we believe them to predate the foundation of Rome, and date from the XIII-XV century A. D.).

Furthermore, “The Historical Notes of Bishop Tria . . . tell us the following: ‘The Slavs, who came from European Sarmatia . . . started to wreak devastation upon Apulia” . . . It is assumed that the Slavs have later founded Montelongo [in Italy – Auth.], and Bishop Tria tells us that back in his time the old men of Montelongo spoke a corrupted Slavic language.

The ‘History’ of Paul Deacon (Book V, Chapter 2), and the Chronicle of Dukes and Princes of Benevent report that new nations came to settle in Italy around 667 A. D.: ‘These nations were the Bulgars, who come from the part of Asian Sarmatia that is washed by the Volga’” ([962], pages 12 and 25). The New Chronology dates this event to the XIV century A. D., identifying it as the “Mongolian” conquest of Italy.

Finaly, the Italian Giovanni de Rubertis reports the following in his article entitled “Slavic Settlements in the Kingdom of Naples”: apparently, the Slavs founded the cities of Montemiro, Sanfelice, Tavenna and Serritello in Italy in 1468 ([962], page 21).

Everything falls into place instantly.

In fig. 15.0 we reproduce a portrait of Alexander Dmitrievich Chertkov.

2. What we know about the Etruscans.

A. I. Nemirovskiy, writes: “A country called Etruria had once existed in Middle Italy, between the rivers of Arno and Tiber. The power of its denizens – the Etruscans, known to the Greeks as Tirrenians, reached to the Adriatic in the East and the North and South of these two rivers” ([574], page 3).

The greatness of the Etruscan fame is reflected well in the very existence of the currently lost encyclopaedia entitled “History of the Etruscans” written by the Roman Emperor Claudius – in twenty volumes, no less ([574], page 3).

“All the incomprehensible inscriptions found in Italy around that time [the late Middle Ages – Auth.] were considered Etruscan; there was even a saying: ‘Nothing is readable in Etruscan’” ([574], page 3).

“In the XIV-XVI century, the area between the rivers Arno and Tiber [or Etruria – Auth.] became the hotbed of the Renaissance culture. Together with a revival of interest in the Greeks and the Romans, the Etruscans become an object of great attention as the oldest inhabitants of Tuscany” ([574], page 3).

Moreover, even in the XVIII century “the study of the glorious history of the Etruscans, whom the inhabitants of Tuscany considered their ancestors, gave the latter moral satisfaction, becoming an outlet for their patriotism” ([574], page 5). The memory of the “ancient” Etruscans was so fresh in the XVIII century, after all!

This is hardly anything to wonder about. “In the municipal archives of the cities of Tuscany there are surviving drawings of Etruscan fortifications, made in the XV-XVI century, and accurate copies of the lettering that covered their walls” ([574], page 3).

And so, in the XV-XVI century there were still Etruscan fortifications in Tuscany – some with Etruscan lettering that is presumed to have survived for twenty centuries on end.

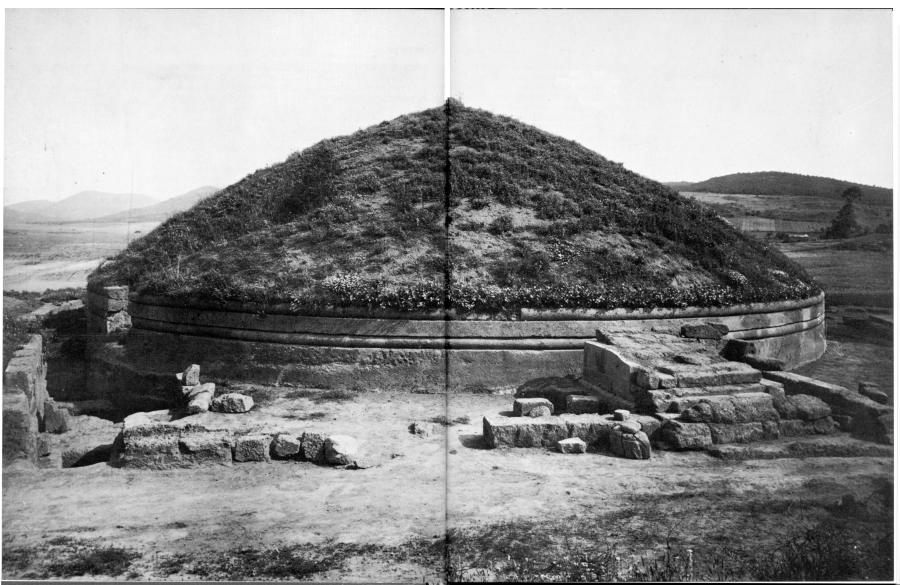

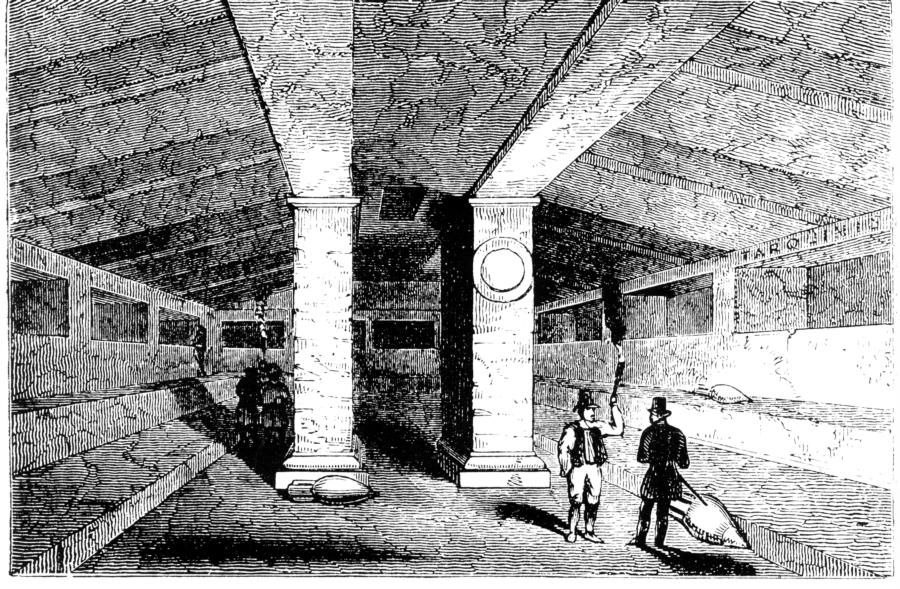

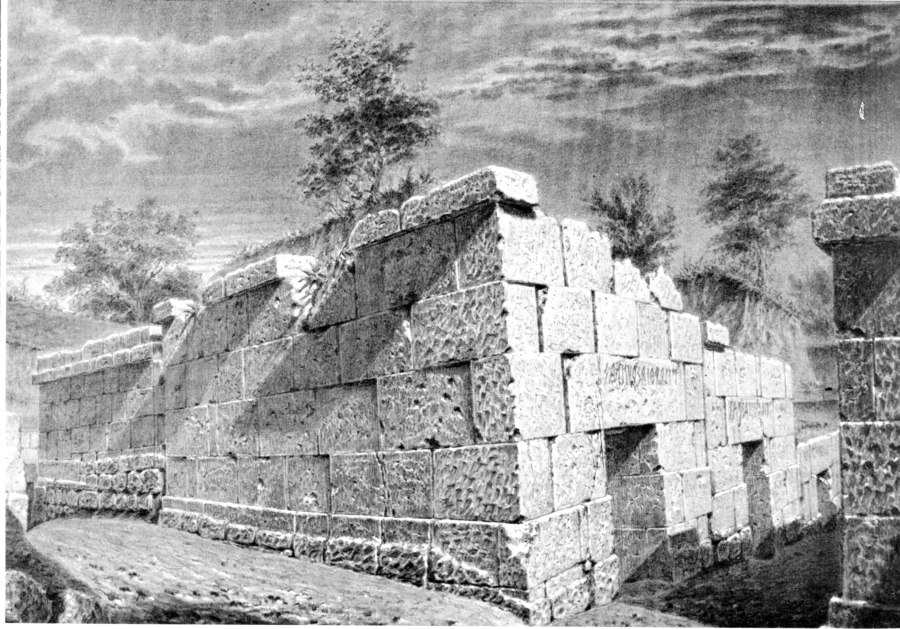

“The Etruscan tombs excited my imagination the greatest. At the end of the XV century many were interested in the excavation tombs and the unearthing of marble columns and statues” ([574], page 3). In fig. 15.1 we see one of the numerous Etruscan graveyards, or necropolises in Italy (the so-called necropoli della Banditaccia a Cerveteri) dated to the VII century B. C. by modern historians. It resembles the Scythian burial mounds. In fig. 15.2 we see the inside of another Etruscan necropolis in Italy, allegedly dating from the VI century B. C. ([1410], page 42). Another kind of Etruscan necropolises is represented in fig. 15.3. In fig. 15.4 we see the remnants of an Etruscan temple.

Now let us provide an overview of the Etruscan studies according to A. D. Chertkov, who calls them “Pelasgians”, as it was customary in his time.

“There are artefacts bearing Pelasgian lettering . . . all across Italy. However, nobody was paying any attention to them before the XV century . . . In 1444, nine large copper plaques were found near Gubbio, with Pelasgian lettering carved upon them. Two of these plaques were taken to Venus, and we have no knowledge of their further fate [destroyed, perhaps? – Auth.] . . .

Although the Gubbio plaques were found in 1444 . . . their real studies only began in 1549 . . . Gori and Bourgeut presumed the language of these plaques to be pre-Trojan, while Freret and Tiraboschi declared them illegible, and the Pelasgian language, lost for eternity . . . It became known as Etrurian eventually” ([956], pages 1-3).

It would be interesting to note that the abovementioned researchers, before even setting down to an in-depth study of the lettering, somehow managed to understand it “instantly” that said lettering was illegible, and that the language itself, lost forever. The fate of the Etruscan studies was foretold for four centuries to come. Whence such foresight? Could it result from a successful attempt of reading the lettering that horrified the researchers so much that they instantly pronounced the language illegible? Study is allowed; interpretation is verboten. This is how it has been to date.

“The interpretation of the lettering was attempted with the aid of the following languages: Hebraic, Egyptian, Arabic, Coptic, Celtic, Cantabrian, Teutonic, Anglo-Saxon, Runic and even Chinese. All of it despite the positive evidence of all the ancient historians and geographers” ([956], page 4).

A. D. Chertkov continues: “A scientist called Ciampi writes it in his “Osservazioni intorno ai moderni sistemi sulle antichita Etrusche, etc” suggested to turn towards the ancient Slavic language for the interpretation of the Etruscan writing (“l’antico linguagio Slavo”). He was trying to convince the Italian scientists of the following: given the futility of Greek and Latin for the interpretation of the Pelasgian writings in Italy, it would make sense to turn towards other languages . . . namely, Slovene (Ingh. Monn. Etrus. II, 233, 468) . . . This happened in 1825; Ciampi had just returned to Italy from Warsaw then, where he had taught for several years as a Professor, and was familiar with the Polish language to some extent” ([956], page 13).

Everything becomes clear. An Italian specialist in Etruscan studies ended up in Poland, studied Polish and was amazed to discover that he can read and, to some extent, understand the Etruscan writing. He was overjoyed, and tried to share the results of his research upon return to Italy. However, this was to no avail – it was pointed out to him that the Germans, the most authoritative scientists in Europe, had proved it long ago that the Slavs appeared on the historical arena in the VI century A. D. the earliest – possibly, much later. And the Etruscans predated Rome by many centuries; in other words, they had existed a long time before the foundation of Rome in the VIII century B. C. Slavic roots were therefore utter nonsense. Ciampi was greatly discouraged.

The above is by no means an invention of ours. We have rendered a passage from A. D. Chertkov’s book more explicitly – he writes the following: “No scientific activity involving the Church Slavonic studies is possible in Italy. Nobody knows our holy language there . . . Of course, it would . . . make sense for them to study Church Slavonic, so as to lift the shroud of obscurity from all the ancient artefacts found in Italy. But the Germans . . . have long ago declared that the Slavs . . . could not have come to Europe . . . any earlier than in the VI century A. D. This is why no one in Italy paid any attention to Ciampi’s claims” ([956], page 13).

Chertkov tells us further: “The first pact signed between Rome and Gabia was set in Pelasgian lettering . . . Polybius reports that in his time even the most enlightened Romans were already unable to comprehend the peace agreement signed between Carthage and Rome in the first years after the banishment of Tarquin. This agreement was written in a language that differs from Latin so much that even Polybius himself was only very barely capable of understanding its text. Therefore, the Romans . . . have completely forgotten their original Pelasgian language, transforming into the Latin race, whose language is of a later origin” ([956], page 4).

Chertkov is perfectly right. The “ancient” Polybius, who must have lived in the XVI-XVII century, according to our reconstruction, was already poorly familiar with the Slavic language spoken in Italy in the XIV-XVI century. The Slavic language started to get extinct from Italy after the banishment of the Tarquins, or TRK – Turks. As we understand, the latter can largely be identified as the Slavs in the epoch in question. The Tarquins were banished in the late XVI or the XVII century, as we understand it – during the European reformation.

“Yet even after that, the folk spoke a language that differed from the written greatly (Maffei, Stor. di Verona, XI, 602). The Oscans and Volscans, even during the efflorescence of the Latin language, retained their dialect, which was understood by simple Roman townsmen – a proof that the scientific Latin language was crafted artificially and differed from the folk dialects of all the Pelasgian tribes” ([956], page 5).

When the humanists of the “Renaissance” epoch and the writers of the XVII-XVIII century already learned how to write in the freshly constructed “ancient” Latin, they must have had to shut their windows well in order to block away the Roman profanes who remained a disgrace to the “ancient” Rome by their use of the vulgar Slavic language.

3. The “antiquity dispute” of Florence and Rome.

“At the end of the XV century, a number of tractates about the Etruscans surfaced in Florence [the capital of Tuscany – see [797], page 1338 – Auth.]. They were written by natives of Tuscany, representatives of the Catholic Church. Cardinal Egidio from Viterbo characterises Etruria as ‘the hearth of the most ancient culture in Italy and an eternal protector and benefactor of religions. Thus, the Christian writer appears to be unaware of the differences between the pagan Etruria and the Tuscany of his epoch” ([574], page 4).

We see that at the end of the alleged XV century (most likely, at the end of the XVI), the Tuscan cardinals remembered the Etruscans very well. A. I. Nemirovskiy shouldn’t try to “justify” the high-ranking patriarchs of the Catholic Church, presenting their actions as a form of “Tuscan patriotism”. We believe that they were telling the truth and do not need to be justified in any way.

<<In the XVI century [most likely, in the XVII – Auth.] completely outrageous conceptions of Etruscan history had reigned – they transformed into what we can call “the Etruscan myth”. Its propagation was assisted greatly by F. Dumpster, the author of “Regal Etruria”, a large work that came out in 1619; it was based on his perception of the ancient authors that hadn’t been sufficiently critical . . . F. Dumpster believed them [the Etruscans – Auth.] to be the very first philosophers, geometricians, priests, builders of cities and temples, inventors of siege machines, doctors, artists, sculptors and pioneers of agriculture. F. Dumpster appears to have completely neglected the question of what remained for the Romans and the Greeks in terms of culture and technology.

The work of F. Dumpster was only published in 1723, some 100+ years after its creation, coinciding with a new surge of interest in the Etruscan history>> ([574], page 4).

It is easy to understand why Dumpster’s book took a century to publish. The time in question is the epoch when “the Austrians were sole rulers of the ancient Etruria; the study of the glorious Etruscan history, considered ancestral by the denizens of Tuscany, gave them a feeling of moral satisfaction and provided a suitable outlet for their patriotism” ([574], page 4-5). Alternatively, we might be confronted with the centenarian chronological shift, which has resulted in the erroneous relocation of Dumpster’s book from the XVIII century to the XVII.

As we have already mentioned, this is the epoch when a campaign of creating an ancient history was implemented in Rome – revised to leave more discoveries creditable to the Greeks and the Romans, qv above. The Tuscan Etruscans were moved further into the past for that end – deep into the antiquity, so as to preclude them from meddling in the affairs of the Great Rome. Many must have been aware of the Etruscans’ true origins back in that epoch – they must have been the Russians that remained here after the Great = “Mongolian” conquest of the XIV century.

Since the history of Russia, or the Horde, also known as “Mongolia”, needed to be distorted as well in order to provide for a more veritable “Italian history of Rome”, the Etruscans were really getting in the way of this “Roman patriotic process”.

This might also be a reflection of some struggle for supremacy between Rome and Florence in actual Italy during the XVII-XVIII century, since Tuscany with a capital in Florence was one of the mightiest republics in mediaeval history. It is known to have struggled against Rome for supremacy, also trying to defend its version of history, according to which the dominant role was played by real Etruscans and not the mythical “ancient Italian Romans” and Greeks.

Vatican of the XVII-XVIII century, which came to replace the former Vatican of the Horde, dating from the XIV-XVI century and a derivative of “Batu-Khan” name-wise, was striving to inculcate its new and blatantly erroneous version of the “ancient Roman” and also the “ancient Greek” history. There was a conflict of interest, and Tuscany has lost. Therefore, the “Etruscophile” work of Dumpster, written in 1629 and reflecting a much more correct version of history than the more recent Roman version, fell under the Roman veto.

It took 100 years to publish – this happened when Tuscany was invaded by the Austrians. The overjoyed Florentines, out of Roman control for a short while, tried to get their revenge, and instantly published the book of Dumpster.

However, they were too late. The false history of the “ancient Italian Rome” was already firmly made part of school curriculum. Everybody was laughing at the Tuscans.

Nevertheless, the Tuscans still attempted to prove themselves right: “In 1726 the ‘Etruscan Academy’ was founded, whose members were the noblemen of Cortona and other Tuscan cities . . . Their reports and claims, void of any serious scientific basis [as A. I. Nemirovskiy tries to warn the reader, compromising the impression left by the work of the Etruscan Academy – Auth.], claimed that nearly all historical works of art were Etruscan in origin – not only in Italy, but also in Spain and Anatolia [Turkey – Auth.]” ([574], page 5).

Moreover, there was a museum of the Etruscan Academy, “counting a total of 81 exhibited items by 1750” ([574], page 5). A. I. Nemirovskiy, being a historian, can’t help crying out in indignation that about three fourths of them “were constituted of forgeries and works of Classical art” ([574], page 5).

The Scaligerites fought the resilient Florentines for quite a while, and only managed to break the backbone of their resistance in the XIX century.

“The first serious [the readers shall see for themselves below just what ‘serious’ means in this context – Auth.] works on the Etruscan studies appeared at the end of the XVIII – beginning of the XIX century. They heralded the first victory of history over the Etruscan myth”, as Nemirovskiy gleefully remarks ([574], page 5).

Why was the myth so resilient, then? Apparently because it was telling the truth.

And so, the version of Italian Rome only proved victorious in the XIX century – it was a domestic victory, since all the foreigners had already complied with the Roman falsification; only the Florentines carried on with their opposition.

4. The two theories of the Etruscans’ origins – the Northern and the Eastern.

4.1. The Eastern Theory.

Until the middle of the XVIII century, it was assumed that the Etruscans came from the Orient – namely, Asia Minor. This is the so-called Eastern theory, based on the authority of many ancient authors. The “ancients” have left us plenty of evidence about the Etruscans in the XIV-XVI century. These “ancient” authors already lived after the Great = “Mongolian” conquest, and managed to describe the dispute between Florence, which became a stronghold of the “Mongolian”, or Russian conquerors, and Rome, the centre of the nascent Catholicism. These descriptions were also declared “ancient” later on.

The dispute only became a possibility in the second half of the XVI century. Before that time, the mighty Florence must have paid little attention to a parochial Italian settlement that had recently titled itself with the lour name of Rome, clearly borrowed from New Rome (Constantinople) or Third Rome (Moscow).

“Over several centuries, even before Rome started to claim supremacy over Italy, the Etruscans reigned over most of the Apennine Peninsula. Therefore, the Greek and Roman historians have written much about the Etruscans” ([574], page 7).

<<The proponents of the theory that the Etruscans came from the Orient were few and far between up until the end of the XIX century, and didn’t have much authority in academic circles. A. Chertkov was among the proponents of the “anachronistic” thesis . . . Chertkov’s interpretation of the Etruscan names is completely anecdotal (as the learned historian A. I. Nemirovskiy assures us – Auth.). However, the numerous anecdotal situations that involve Chertkov do not diminish any of his numerous merits . . . He brought the Etruscan issue out into the broader historical and linguistic arena, acting as a forerunner to many of the modern researchers>> ([574], pages 9-10).

“In Russian science, argumentation in support of the ‘oriental thesis’ was provided by V. Modestov” ([574], page 10).

Further also: “French scientists, for but a few exceptions, were supporters of the Oriental theory insofar as the Etruscans were concerned . . . The problem of the Etruscan origins was researched by V. Brandenstein for a long time . . . He voiced his support of the theory that the Etruscans came from the Orient . . . Indo-European elements of the Etruscan language were explained by the contacts between the Tirrenian populace and the Indo-Europeans in the East. He has found a number of Turkicisms in the Etruscan language. This gave him reasons to assume that . . . the ancestors of the Etruscans had lived in Central Asia, whence they migrated to the Northeast of Asia Minor” ([574], page 13). Then the Etruscans came to Italy from Asia Minor.

Actually, V. Brandenstein eventually “abandoned the Turkic thesis” ([574], page 13). It is easy enough to understand why – he must intuitively realised that the implied corollaries are way too dangerous.

What did the Etruscans actually look like as a people? “Analysing the data that characterise the religion and the art of the Etruscans, as well as their language, P. Ducati . . . points out a few traits alien to the Latin nations and to other peoples residing in Italy. He believes this to be sufficient reason to support the old tradition about the East Mediterranean roots of the proto-Etruscans” ([574], page 11).

So much for the “Eastern” theory.

4.2. The Northern theory.

In the middle of the XVIII century, N. Freret suggested another theory, according to which the proto-Etruscans came from the Alps. “This is how the ‘Northern Version’ of the Etruscan origins came into existence, based upon nothing in the ancient tradition and by now completely abandoned by its proponents. Nevertheless, in the XIX century it had been regarded as possibly the sole key to the mystery of the Etruscan origins, especially by the German scientists” ([574], pages 7-8).