Part 5.

Ancient Egypt as part of the Great “Mongolian” Ataman Empire of the XIV-XVI century.

Chapter 16.

History and chronology of the “ancient” Egypt. A general overview.

1. Our hypothesis.

Let us formulate the hypothesis right away. Such a generalised first glance at the extremely rich Egyptian history might help the reader to get a better orientation in the details of further research.

1. History of Egypt gradually emerges from obscurity only starting with the XI-XII century A. D.

2. The period of Egyptian history between the XI and the XIII century appears to be covered in the documents that have survived until our day and age very sparsely.

3. The history of the Ancient Russia is closely interwoven with that of the African Egypt. The documented and archaeological history of the “ancient” Egypt in Africa is primarily the history of Egypt as a part of the united Great = “Mongolian” Ataman Empire of the XIV-XVI century A. D.

One needn’t think that the “Mongols”, or the “Great Ones”, who invaded Egypt in the beginning of the XIV century, have remained a Russian and Turkic nation for the centuries that followed. They have populated the centre and the north of Africa, subsequently assimilating and forgetting about their origins. However, they have greatly contributed to the history and the culture of mediaeval Egypt.

4. The famous thirty “ancient” dynasties of the Egyptian pharaohs are for the most part phantom reflections of real Ataman dynasties of the Horde dating from the XIII-XVI century.

5. The “ancient” Egyptian pharaohs were Russian and Turkic Czars, or Khans, of Russia, or the Horde, and the Ottoman (Ataman) Empire. They lived and reigned in Russia, or the Horde. They very seldom appeared in African Egypt while they were still alive; however, after they died, they were brought here to be buried at the central imperial “Mongolian” graveyard – in particular, to Gizah and to Luxor.

6. Biblical Egypt can be identified as Russia, or the Horde, in the XIV-XVI century. See CHRON6 for more details.

2. A brief account of the mediaeval Egyptian history.

Our reconstruction implies that the history of the “ancient” Egypt is but a multiple phantom reflection, or duplicate, of its mediaeval history between the XI and the XVII century, qv in CHRON1-CHRON3. This is why virtually every event in Egyptian history known to us today is most likely to date from the Middle Ages – the XI century the earliest. These events became multiplied in various chronicles, partially remaining in their “rightful place”, or the XI-XVII century, and partially shifted into deep antiquity by the Scaligerite chronologists.

Let us see whether our conception might aid our understanding of the “ancient” Egyptian history in any way at all, seeing as how Egypt is a country associated with many historical mysteries, such as the epoch when the gigantic pyramids, the Great Sphinx and other grandiose constructions of the “ancient” Egypt were erected, as well as the identity of their builders. However, let us first provide a brief account of the mediaeval Egyptian history in its Scaligerian rendition. We shall be referring to the famous fundamental work of Heinrich Brugsch, a famous German Egyptologist of the XIX century, entitled “History of the Pharaohs” ([99]), with notes by G. K. Vlassov.

It turns out that the early XIII century is the “break point” and the beginning of the new epoch in Scaligerian history of mediaeval Egypt. This is where the old Eyubid dynasty ends and the new Mameluke dynasty begins, qv in fig. 16.1. The dates cited below, up to the end of Paragraph 2, are Scaligerian.

1201-1202 – plague and famine in Egypt.

1240 marks the ascension of the last Eyubid – “Eyubid Salekh; the famous Mameluke guard is formed during his reign, which had primarily consisted of Cherkassians and other highlanders from the Caucasus” ([99], page 745).

Salekh-Eyub died in 1250, and the Mamelukes seized power. Led by Fahreddin initially, and by Turan-Shah after Fahreddin’s death, they deflect the assault of the French – the crusade of Louis IX the Saint. The Crusaders were defeated in 1250, and Louis the Saint was taken prisoner. “Shagaredor, the widow of Salekh-Eyub, rules over the kingdom together with the Mameluke Council, which is the most influential party” ([99], page 745).

Ibek the Mameluke is crowned Sultan ([99], page 745).

In 1253 Egypt and Syria sign a truce ([99], page 745).

Up until 1380, Egypt is governed by the Bakharit Mamelukes, or the Bagherids ([99], page 745).

Between 1380 and 1517 Egypt is ruled by the Cherkassian Sultans ([99], page 745).

1468 marks a war against the Turks ([99], page 745).

In 1517 Selim I, Sultan of Turkey, defeats the Mameluke army in the Battle of Cairo. The Turks come to power ([99], page 745).

In 1585 the Mamelukes recapture the power in Egypt and reign there up until the end of the XVIII century ([99], page 745).

In 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte disembarks near Alexandria in Egypt. The French invasion into Egypt begins; the Mamelukes Murad and Ibrahim retreat ([99], page 745).

On 21 July 1798 the historical battle near the Great Pyramids is fought ([99], page 745).

22 August 1798 is the date of the Battle of Abukir, which basically marks the end of the Mameluke dynasty in Egypt ([99], page 745).

In 1811 a massacre of the Mamelukes took place ([99], page 745).

We shall soon need this synopsis for reference. Now let us briefly recollect what we know about the “ancient” history of Egypt.

3. The erroneous Scaligerian foundation and the objective difficulties inherent in the consensual chronology of Egypt.

“The main error of the official science isn’t the

chronology that it suggests, but rather the noncommittal

manner that it is presented in, while the actual

chronology is usually based on very meagre and even

perfectly ephemeral proof”.

Jorge A. Livraga, “Thebes” ([484], page 34).

It is believed that before the Napoleonic invasion into Egypt in 1798 this country had largely remained closed for European travellers.

There are assorted pieces of evidence presented by the Arabs that concern Egypt in the IX-XVI century and are nowadays believed to be of a figmental nature for the most part ([464], pages 39-43). For instance, it is said that one of the pyramids concealed “a swimming pool filled with golden coins . . . the actual pool is said to have been made of emerald” ([464], page 39).

Kaisie, an author of the alleged XII century, reports the finding “of a human body inside a pyramid, clad in a golden cuirass adorned with all sorts of gemstones, with a priceless sword upon its chest and a red ruby at its head, large as a hen’s egg and burning bright as fire” ([464], page 40). And so on, and so forth. However, it might be that such mediaeval evidence isn’t fiction, but rather largely true and referring to the lavish royal sepulchres in Egypt dating from the epoch of the XIV-XVI century, robbed by the Europeans later, after the dissolution of the Empire in the XVII century.

“Mediaeval pilgrims who dared to take a look at these monuments demonstrate an even greater ignorance” ([464], page 44). In the alleged year 1336 these parts were visited by Wilhelm de Boldensele ([464], page 43). The next one was Chiriaco of Ancona – already in the XV century, or 1440 A. D. ([464], page 43).

It is believed that the first “reasonable” conceptions of Egypt were formed in Europe as late as at the end of the XV century ([464], page 46). Apparently, the first attentive researchers who made their way to mediaeval Egypt were the Jesuits – fathers Protius and Francois ([484], page 78). Lager, in the XVIII century (1707) another Jesuit, Claude Siquart, was sent to Egypt as a missionary at the personal order of the French king in order to draw a plan of the Egyptian antiquities ([484]], page 78). It is believed that “with the books of Strabon and Diodorus of Sicily at his disposal, he was capable of estimating the sites of Thebes and the Theban necropolis correctly” ([484], page 79).

What we see is de facto a repetition of the story with Marco Polo’s book, already well familiar to us. A European traveller of the XVIII century comes to Egypt armed with “ancient” literature and begins to “discover” the names contained in the books “on site”. For instance, it is believed that he was the discoverer of the famous “Thebes of 100 Gates” (we shall come back to it later).

“Many of his papers ended up in France, and their extracts were published by the Jesuits . . . Some part of the extremely valuable materials that he had collected was lost . . . This discovery awakened the curiosity of his numerous contemporaries. If we are to believe the lettering from one of the sepulchres, which has become obliterated or simply lost [?! – Auth.], another priest, Richard Pocock, visited the Valley of the Kings on 16 September 1739” ([484], page 79).

How are we supposed to understand it? The missionary wrote his name upon an ancient Egyptian sepulchre? Modestly chiselled it on one of its walls, perhaps? Could he have erased something as well, while he was at it? Does this imply that the first Catholic missionaries of the XVIII century tampered with the lettering found upon Egyptian artefacts?

“In 1790 James Bruce released five voluminous books containing an excellent oeuvre on Egypt. His journey was undertaken in 1768” ([484], page 79).

At last, JESUITS appear by the end of the XVIII century in Egypt and start to form the "ancient Egyptian" history, apparently carrying out some "work" with the inscriptions.

"At the end of the 18th century, other digs were undertaken at the location difficult to DETERMINE accurately. At that time they received the general label of TURKISH digs(! -Auth.) because of Egypt by that time BECAME A PART, albeit remote, of residues of the Ottoman Empire "[484], p.79.

In re the actual name of Egypt. “In the ancient writings, as well as in the books of later Egyptian Christians, Egypt is referred to by a word that translates as ‘black land’ – ‘Kem’ or ‘Kami’ in Egyptian . . . It has to be noted that the name ‘Egypt’ hadn’t been known to the dwellers of the Nile region . . . Wilkinson was one of the scientists to voice the opinion . . . that the word ‘Egypt’ derives from the name of a town called Koptos or Guptos” ([99], page 77).

According to Brugsch, “the name that was used by the foreign nations of Asia for referring to Egypt is a real mystery in what concerns its origin and its meaning. The Jews called it Mizraim, the Assyrians – Mutsur, and the Persians – Mudraya” ([99], page 78).

According to N. A. Morozov ([544], Volume 6), the name Mizraim derives from that of Rome and translates as “arrogant Rome”. We shall refrain from discussing the correctness of the “arrogant” part – it is of little importance to us. However, we must definitely note the obvious presence of the name “Rome” in the “ancient” name of Egypt.

We see that real information concerning Egypt only started to reach Europe in the late XVIII – early XIX century, which is very late indeed. Therefore, the nascence of Egyptology as a science also dates from a very recent period – namely, the XIX century. This fact is commonly known, and was discussed at length in CHRON1.

The first Egyptologists were working within the framework of the already existing erroneous chronology of Scaliger and Petavius. This is why the scientists were trying to attach the fragments of Egyptian chronological information to the artificially elongated “spinal column” of the Graeco-Roman chronology. This primary, and apparently involuntary error of the first Egyptologists was aggravated further by objective difficulties such as the poor condition of the Egyptian chronological sources.

As we have mentioned it in CHRON1, it turns out, for instance, that the work of Manethon has not reached our days – it was lost, and we only know about it from Christian sources. We are of the opinion that this simply means that the initial rough scheme of Egyptian history was drawn up within the framework of the Occidental Catholic Church, since, according to our reconstruction, the history of Egypt isn’t any longer than that of the Christian Church. First the Egyptian Christian monks recorded the history of their “ancient” Egypt, or the Egypt of the XII-XVII century A. D. Then these records, which ended up in Europe after the conquest of Egypt, were edited by European historians in the XIX century. This is what Brugsch tells us about the work of Manethon.

“Historians of the Classical antiquity were hardly aware of this precious book’s existence at all, and didn’t use any of the indications contained therein; it was only later that certain authors from the Christian Church compiled a collection of excerpts from this book. Later on the scribes distorted the names and the figures contained in Manethon’s original, either deliberately or as a result of errors, and so all we have at our disposal is a pile of ruins instead of a structured edifice” ([99], page 96).

In CHRON1, Chapter 7:7.2 we reported that the Egyptologist H. Brugsch “dated” the Egyptian dynasties in a very odd fashion, ascribing 33.3 years to each pharaoh, counting three pharaohs per century. We might hear the suggestion that Brugsch was following Herodotus when he used this dating method.

Indeed, according to G. K. Vlastov, “Brugsch . . . counts three generations per century, just like Herodotus” ([99], page 69, Comment 1). However, this does not excuse Brugsch in any way at all, since he had lived some two or three centuries later than Herodotus, who must have written his work in the XV-XVI century A. D., and should have approached the chronological foundation of the edifice of ancient history, constructed by himself and his colleagues, a great deal more seriously. After all, science made great advances over the course of two or three hundred years, and such uncritical reiteration of the statements made by Herodotus appears perfectly unacceptable.

It is all the more bizarre that, despite following Herodotus in this “dating method”, which is strange to say the very least, Egyptologists of the XIX century, likewise their modern counterparts, are for some reason reluctant to follow other chronological conceptions of the very same Herodotus, which strike us as much more natural.

As we point out in CHRON1, Chapter 1:4, the time intervals between some of the pharaohs are a great deal shorter than the respective intervals according to Manethon, that have reached us in the “rendition” of the late mediaeval Christian authors.

It is obvious that some important chronological conceptions of Herodotus fail to fit into the chronological framework invented by the chronologists of the XVI-XVIII century and uncritically perceived by their laborious followers, the Egyptologists of the XIX century.

Why did the Egyptologists of the XIX century adopt the abstract “dating method” of Herodotus (three generations per century), which was never actually used by Herodotus himself, refusing to believe his direct chronological indications concerning the order of succession and so on?

The answer appears to be obvious. The nebulous “dating method” of Herodotus could be made correspond with the erroneously and arbitrarily elongated chronology of Scaliger, which had already dominated the minds of the XIX century Egyptologists, whereas the direct indications given by Herodotus, such as the fact that Cheops reigned immediately after Rhampsinitos (Ramses II), qv in [163], 2:124, page 119 and also CHRON1, Chapter 6, didn’t leave anything of the chronology developed by Scaliger and his predecessors of the XV-XVI century. This is why they were cast into oblivion by such comments as quoted in CHRON1, Chapter 6, so as nobody would pay any attention.

Incidentally, it is perfectly justified to enquire whether Herodotus was correct to state that Cheops reigned immediately after Rhampsinitos, or Ramses II. Our reconstruction confirms this declaration made by Herodotus – he was in fact correct, as we shall soon witness.

Our opponents might ask about the radiocarbon dating, which is presumed to have confirmed the great antiquity of the Egypt of the pharaohs. However, it turns out that the radiocarbon method in its modern state is unfortunately incapable of answering the important question that concerns the age of the objects whose age amounts to a mere millennium or two. This is covered in detail in CHRON1, Chapter 1:15.

In CHRON1-CHRON3 we give a detailed account of the astronomical dating of certain “ancient” Egyptian sources, such as horoscopes (zodiacs). It turns out that astronomical dating yields the dates from the interval of the XII-XIX century, qv in CHRON1, Chapter 3.

4. The “ancient” Egypt of the Pharaohs as a Christian country.

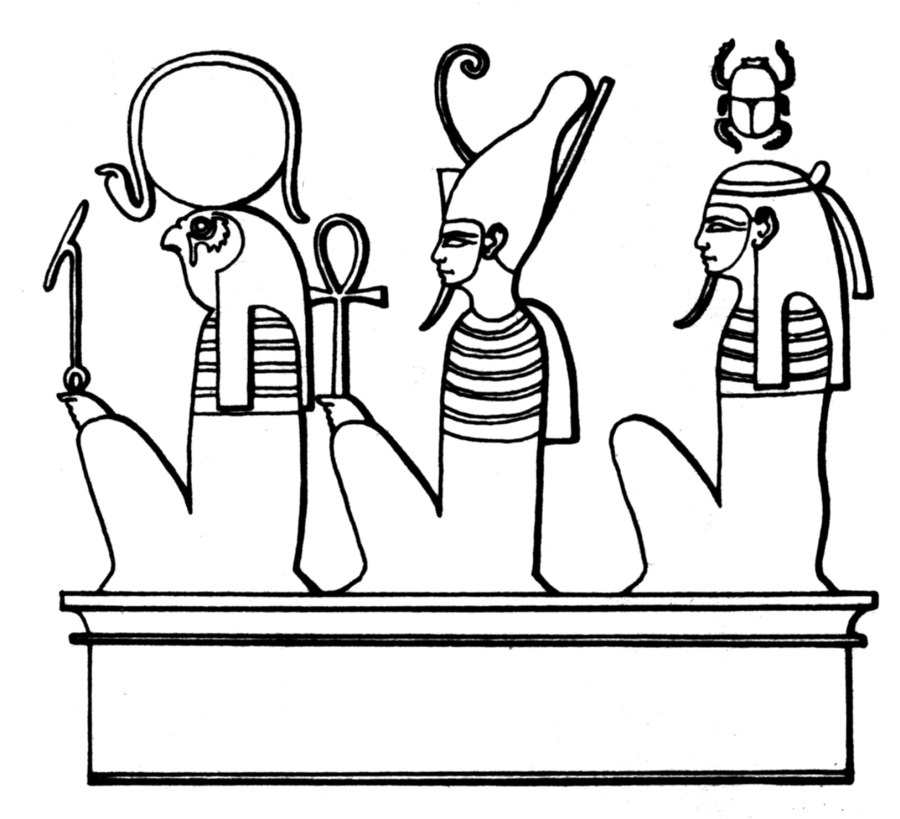

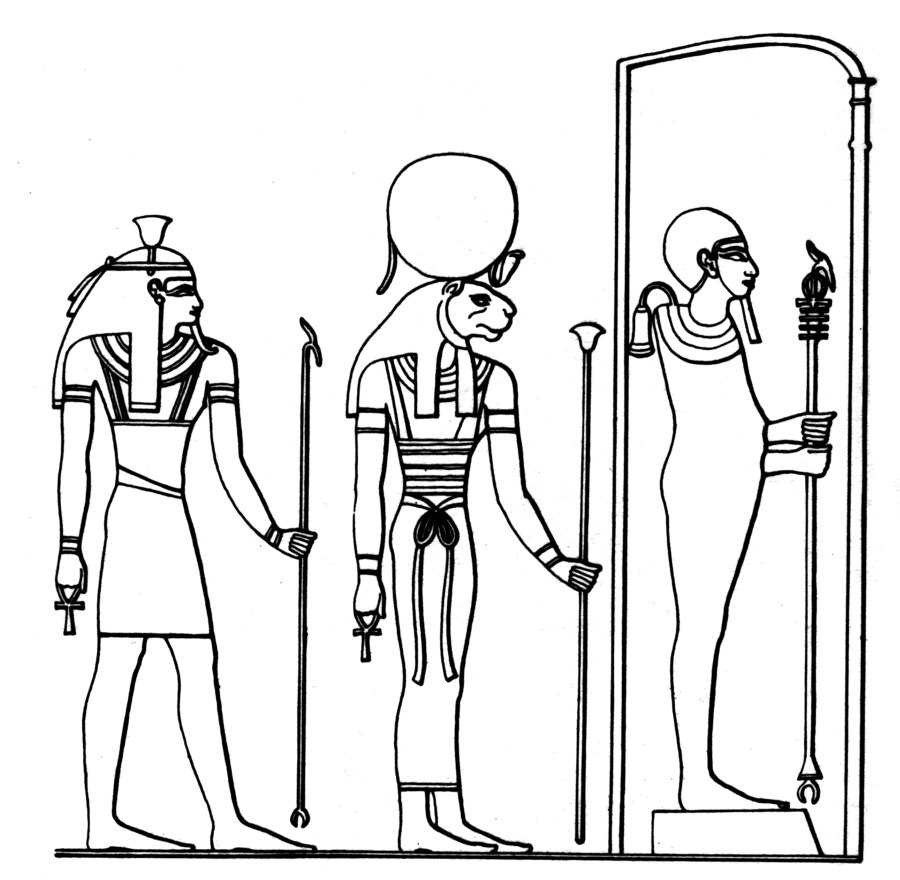

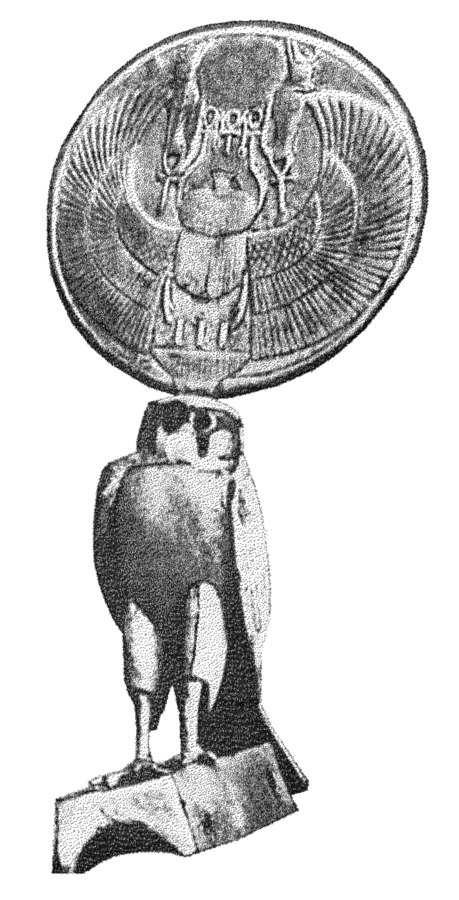

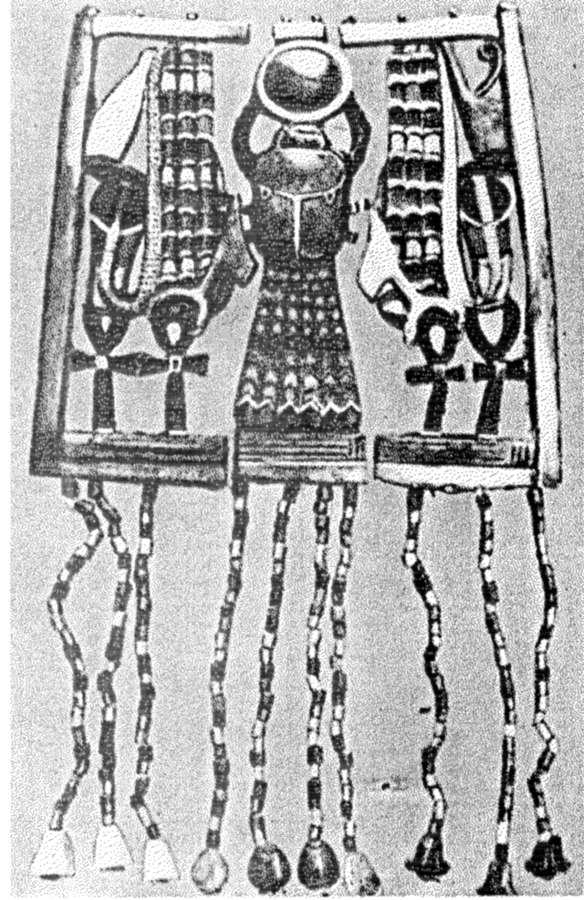

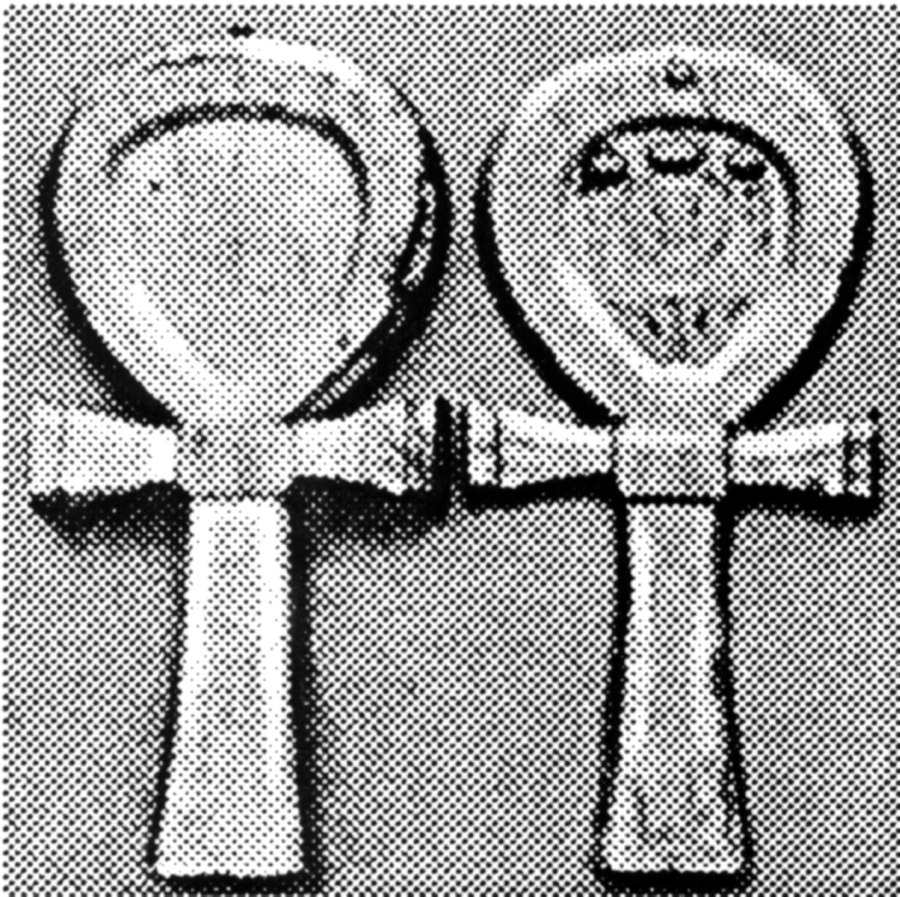

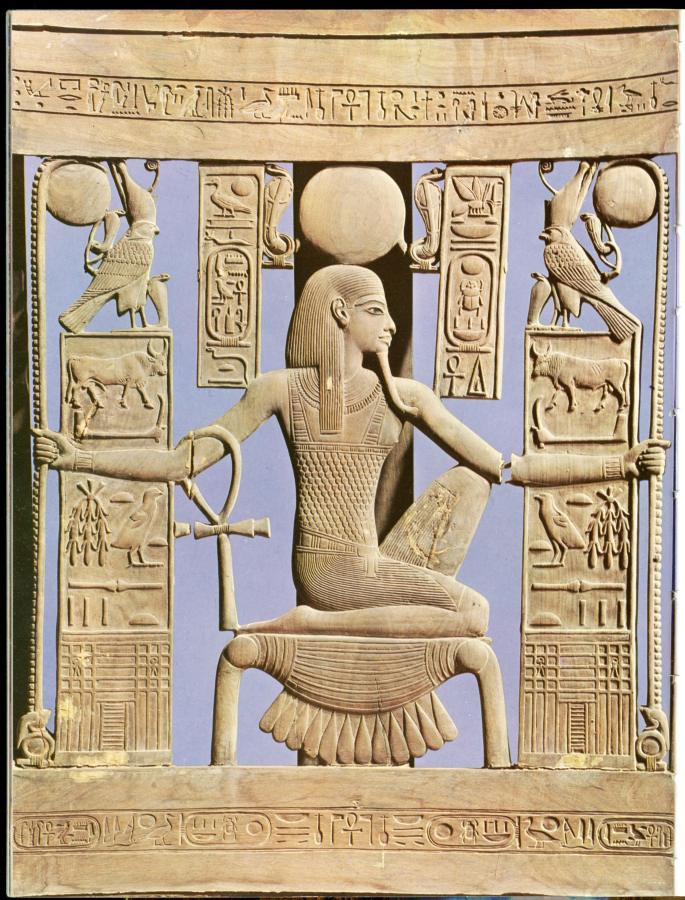

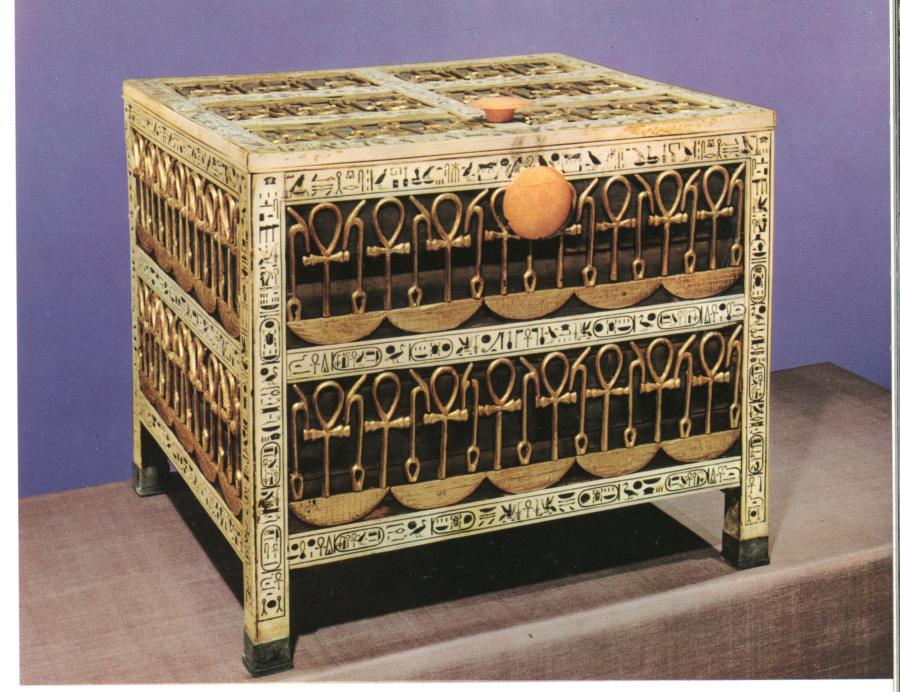

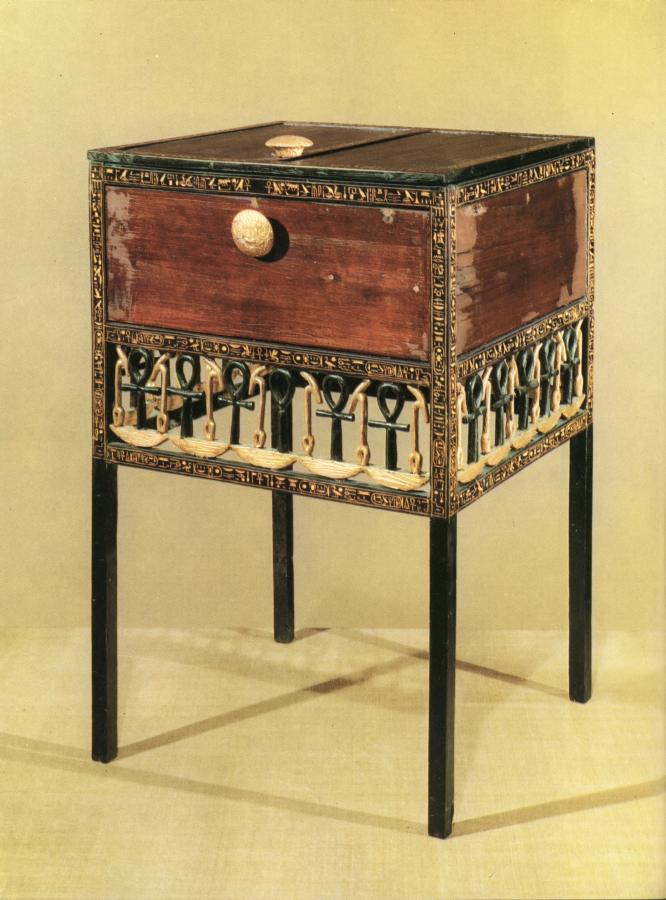

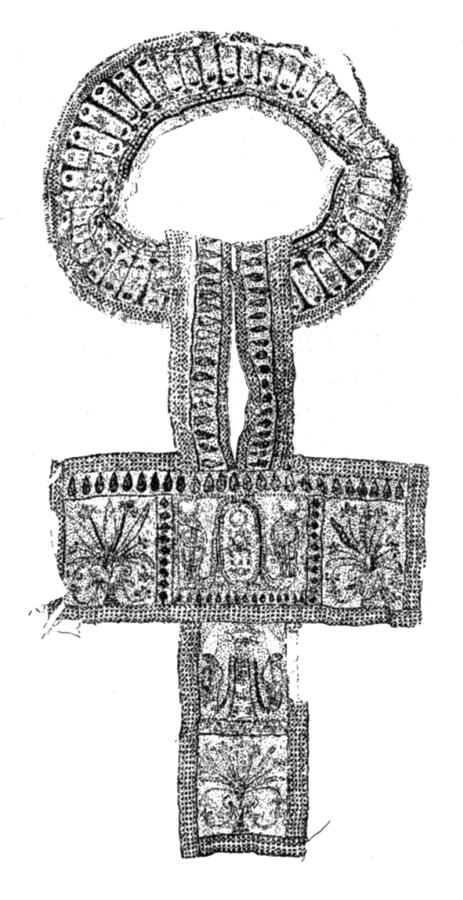

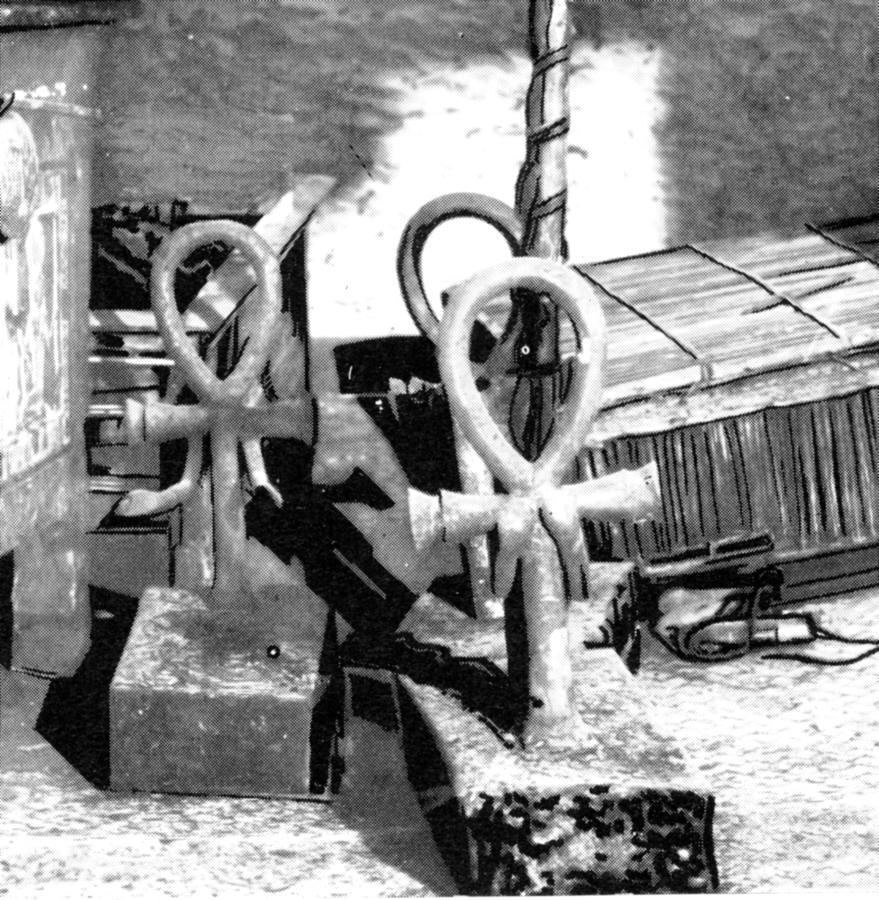

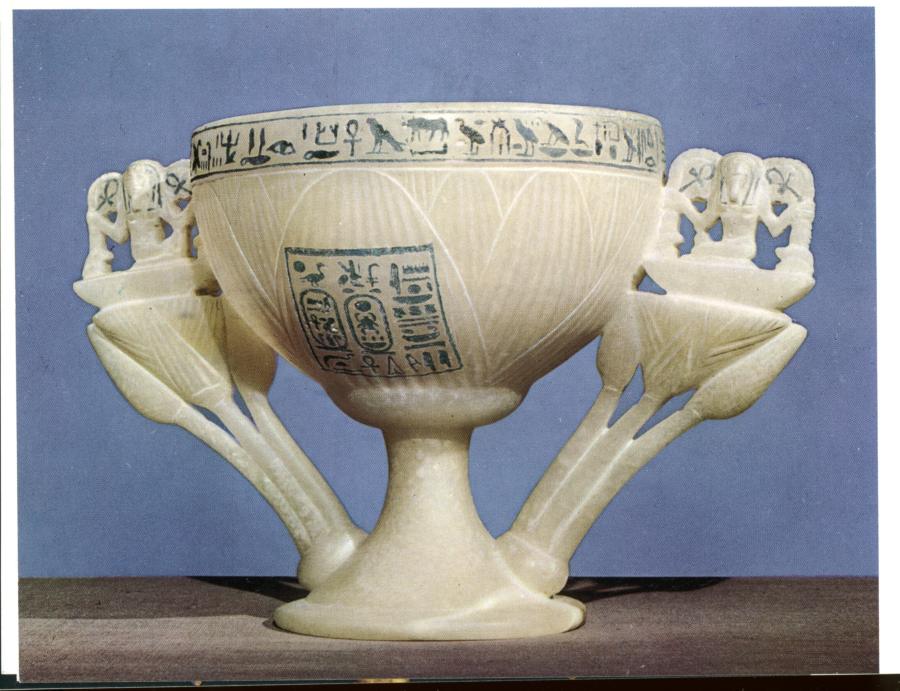

As we mention it in CHRON1, Chapter 7:6.3, the documents and artwork of the “ancient” Egypt clearly reveal Christian motifs known well to us from the history of the Middle Ages. Even in Scaligerian history, the “ancient” Egypt is considered the classical “land of the crosses”. Many of the “ancient” Egyptian deities as portrayed on drawings, carvings, pharaoh monuments and so on are depicted holding one of the mediaeval anagrams of Jesus Christ in their hands – the so-called “Coptic cross”, or an ankh (see fig. 16.2 and also CHRON1, Chapter 7:6.1).

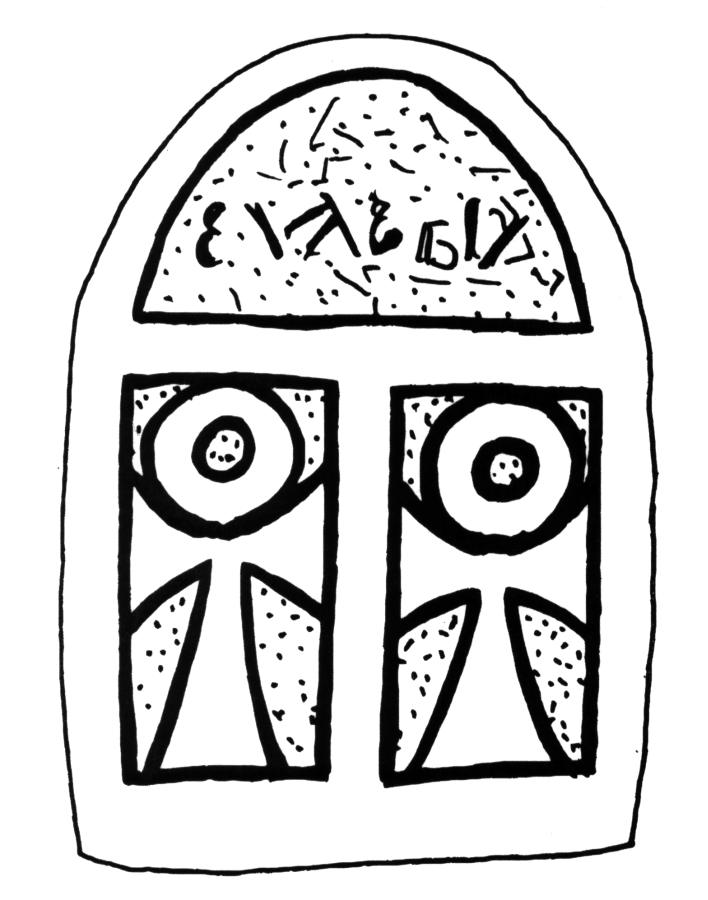

In figs. 16.3 and 16.4 we see some of the “ancient” Egyptian crosses, which are completely identical to the mediaeval representations of the Christian Coptic crosses, qv in fig. 16.5 and 16.6. See CHRON1, Chapter 7:6.3 for more detailed.

“Egyptian kings and queens are often depicted holding this sign [the Coptic cross] in one of their hands, just like Apostle Peter and his key . . . One of the Egyptian monuments dated to the XV century B. C. by the specialists, the cross is depicted inside a circle, without any ankh loops”, as we learn from A. P. Goloubtsov, an eminent specialist in the field of ecclesiastical archaeology ([176], page 213). Further on he tells us the following about the possible meaning of the cross symbol as used by the Egyptians: “The cross on the chest of the Egyptian mummies, likewise the crosses on the Etruscan tombstones, may have evolved and been used as a holy symbol of life itself” ([176], page 213).

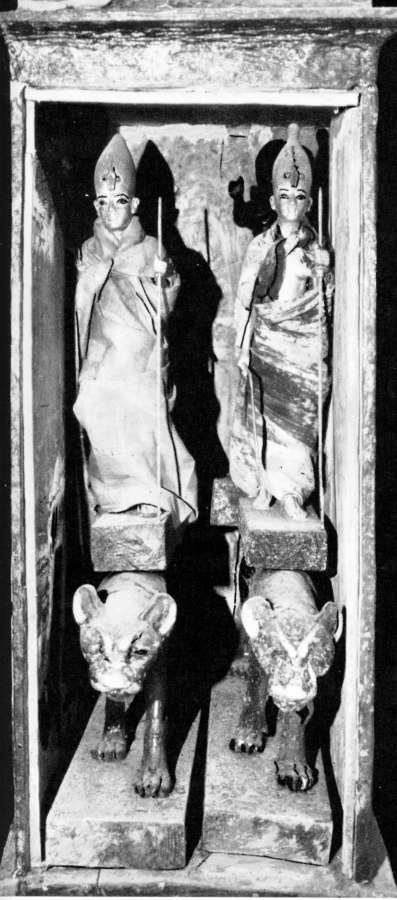

The findings from the tomb of Tutankhamen are of the greatest interest indeed (given that they are authentic ancient artefacts as opposed to objects manufactured in the XIX century – see below for more details). Some of them are represented in figs. 16.7, 16.8, 16.9, 16.10, 16.11, 16.12, 16.13, 16.14, 16.15, 16.16 and 16.17. We feel obliged to state it once again that the crosses found depicted upon these objects (which the Egyptologists prefer to call ankhs, or symbols of life) do not differ from the mediaeval Coptic crosses in any way at all.

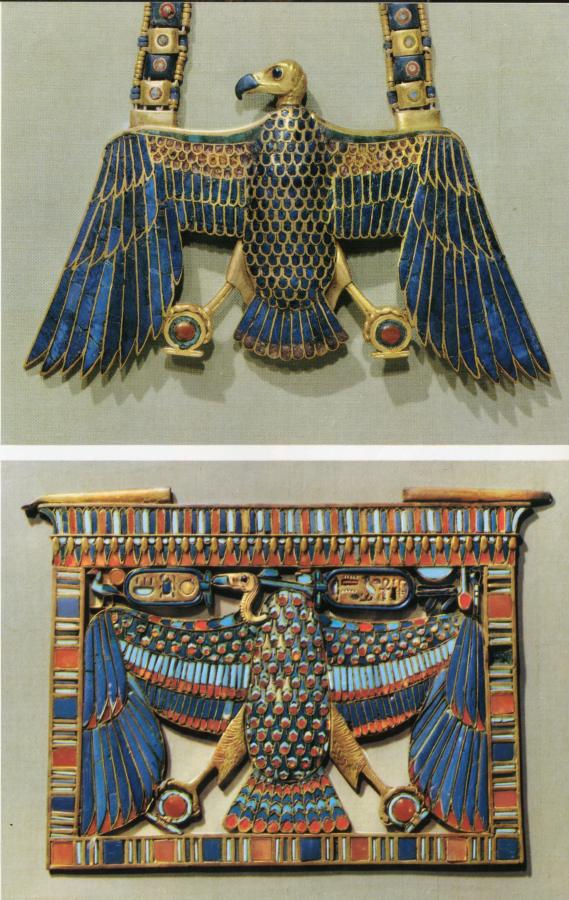

In figs. 16.18 and 16.19 we see the “ancient” Egyptian coats of arms, which are virtually identical to the “Mongolian” eagle, drawn as the Ottoman = Ataman crescent in fig. 16.19.

The cross is often drawn alongside a cobra (also known as the Ureus) – a symbol often found on the headdress of the pharaoh and the Sphinxes. This is a clear indication that the famous snake of the Pharaohs, known as the Ureus, is also a Christian symbol, presently forgotten. Moreover, in some of the “ancient” Egyptian drawings the Ureus snake has the shape of the cross (see figs. 16.20, 16.21 and 16.22).

It would be interesting to point out that in Christian mythology the serpent isn’t necessarily a negative symbol. “According to the beliefs of the Serbs, the Snake is often a positive character, a protector of his genus and a hero . . . equal to God and the Saints in holiness. According to the beliefs dominant in Montenegro, the Russian imperial family, much revered in Serbia and Montenegro, can trace its ancestry back to the Snake” ([781], page 197).

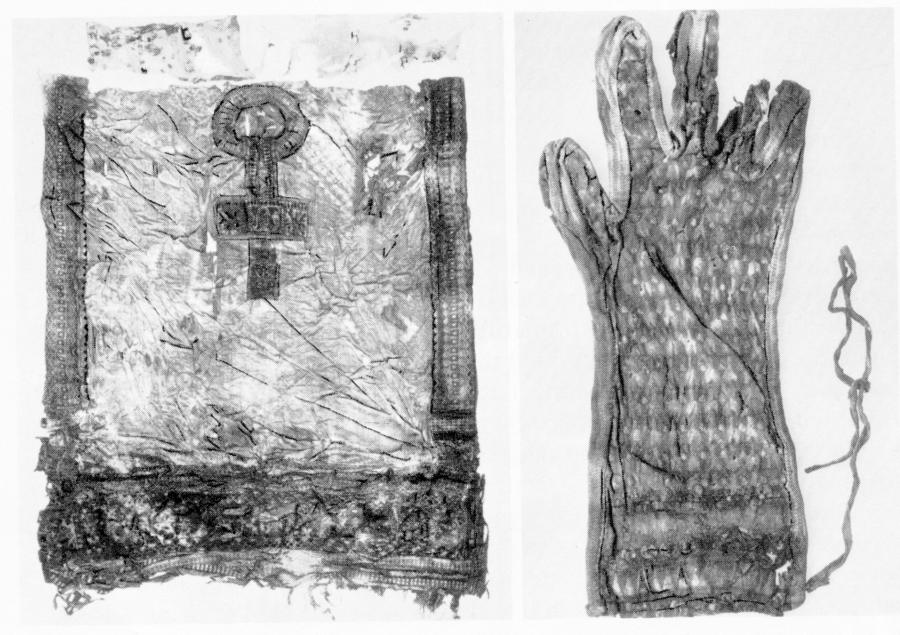

In fig. 16.23 we see a linen shirt with embroidery that resembles a Christian cross – the “ancient” pharaoh Tutankhamen was buried in this garment ([1101], page 270). In fig. 16.24 we see this embroidered cross separately. Moreover, it turns out that the pharaoh wore gloves ([1101], page 270). One of them can be seen in fig. 16.23. Gloves happen to be a typical mediaeval accessory.

As for the linen attire of the priests with cruciform embroidery (as seen in fig. 16.13), G. Carter reports the following: “The two clothing items that I would prefer to call festive attire clearly resemble official attire of the deacons and the bishops . . .

I am not making any claims about having conducted any historical research concerning such clothes, but the fact that I managed to find fragments of such clothes bearing the name of Amenkhotep II in the sepulchre of Thutmos IV implies that every pharaoh had a garment of this sort” ([374], pages 236-237).

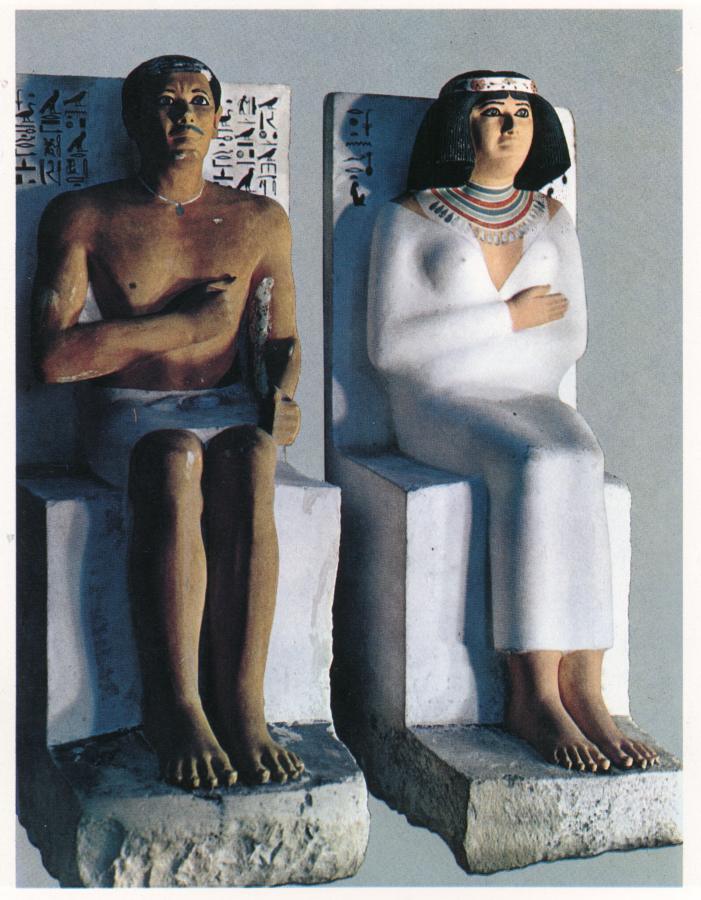

Linen clothing wasn’t only worn by Tutankhamen. In fig. 16.25 we see the “ancient” Egyptian statue of Nephert, the wife of Pharaoh Rakhotep from the fourth dynasty. According to the Egyptologists, “the princess is wearing . . . a linen dress and a wig” ([728], page 31).

One must also pay attention to the “ancient” Egyptian candlesticks shaped as Coptic crosses found in the sepulchre of Tutankhamen (see fig. 16.26). They resemble Christian crosses installed over graves. Similar crosses can be found upon the “ancient” alabaster chalices, lamps and so on (see figs. 16.27 and 16.28).

In fig. 16.29 we see a golden piece of “ancient” Egyptian jewellery from Meroe. Six Christian crosses form a chain. A similar golden chain from the “ancient” Egypt, comprising a total of eight Christian crosses, can be seen in fig. 16.30.

Many similar examples can be easily found in any more or less extensive album on the “ancient” Egyptian art.

Our reconstruction provides a good explanation for the numerous Evangelical motifs reflected in the artefacts from pharaoh Egypt. We have mentioned some of them in CHRON1, Chapter 7:6.3. Apparently, the “ancient” Egypt was part of the Byzantine Christian state in the XII-XIII century, and then the Christian “Mongolian” Empire of the Atamans and the Horde in the XIV-XVI century.

Jesus Christ appears to have lived in the XII century A. D., and therefore all these “amazing” monuments from the “ancient” Egypt with Evangelical artwork upon them cannot possibly predate the XII century. The emperor Andronicus-Christ (also called Russian Prince Andrey Bogolyubsky, idem Apostle Andrew the First) was crucified in 1185 in Czar-Grad; see our book "The Czar of the Slavs".

For example, let us consider how the name of the solar god was transcribed in the epoch of Pharaoh Ekhnaton: “Long live Ra-Khar-Akht, rejoicing in the sky, whose name is Shov and also Yoth” ([650], page 18; see also [1249]).

It isn’t too hard to identify the name “Shov, and also Yoth” as that of Sabaoth (given the flection of S/Sh etc, and the possibility of different vocalizations as mentioned above).

Scaligerian history is well aware of the popularity of Coptic Christianity in the mediaeval Egypt. Hence the very name of Egypt, or Gypt (which is derived from the word Copt, according to [99]).

The explanation is very simple – mediaeval Egypt is the same country as the “ancient” Egypt.

5. The construction tools used by the “ancient” Egyptians.

Since the enormous Egyptian stone constructions date from the deepest antiquity in Scaligerian chronology, reasonable researchers have long been asking the following question.

How could the “ancient” Egyptians have built all the Gargantuan stone constructions, such as pyramids, obelisks, sphinxes, temples and so on, with the use of the primitive tools that are said to have been available several thousand years before the new era – stone axes, wooden wedges, cane ropes and so on. A propos, Europeans in Scaligerian history had still lived in cold caves and wild woods back in that epoch.

Jorge A. Livraga writes the following, for instance: “Many of Egypt’s largest constructions . . . could not have been built with the use of the methods and materials that are presumed to have been employed by the builders . . . We also know nothing of how the Egyptians managed to drill the hardest diorite for their canopies with such ease, which is implied by the measurements of the depth of a drill’s penetration over the course of a single turn” ([484], page 35).

Let us put forth the following hypothesis. Since our reconstruction claims that nearly all these constructions were built in the XIV-XVII century A. D., these drills were made of steel – possibly with diamond heads.

Our hypothesis receives the following indirect confirmation. We have already referred to this fact in CHRON1: “One frequently encounters mentions of a steel chisel found in the external stone masonry of the Khufu Pyramid (the Cheops pyramid dating from the early XXX century B. C.”. Michele Giua instantly tries to calm down the alarmed reader as follows: “However, it is most likely that this instrument got there during a later epoch, when the stones of the pyramid were taken away as construction material” ([245], page 27, comment 23).

Moreover, below we shall acquaint ourselves with the hypothesis of the French chemist Joseph Davidovich, Professor of the Berne University, according to which the “ancient” Egyptian builders had widely used concrete. If this is indeed the case, the mysteries of the megalithic constructions in the “ancient” Egypt disappear.