Part 5.

Ancient Egypt as part of the Great “Mongolian” Ataman Empire of the XIV-XVI century.

Chapter 16.

History and chronology of the “ancient” Egypt. A general overview.

10. The destruction of inscriptions found on the ancient artefacts of Russia and Egypt.

In CHRON4 we describe the Romanovian destruction of the XIV-XVI century artefacts from Russia, or the Horde, which took place in the XVII-XVIII century. A great many frescoes, stone sarcophagi and even cathedrals were either destroyed or gravely mutilated in the Romanovian epoch, qv in CHRON4, Chapter 14:5.3. We are confronted by a very important fact – the matter is that the defacement of tombstone inscriptions didn’t only happen in Russia.

For example, in Egypt “the names of many kings were meticulously removed from the monuments built in their lifetime” ([624], page 21). Apart from the fact that the names were chiselled off the walls of the sepulchres, we learn that the actual mummies were smashed to dust with hammers ([624], page 21). When was it done, and for what purpose?

Nowadays the historians try to answer this obvious question in the following manner. It is presumed that when a pharaoh was buried, a council of judges was appointed, and the people would decide whether the pharaoh in question was worthy of a burial. If the pharaoh was declared “evil”, he was “deprived of burial”. But, as we are told, the sepulchres were constructed in advance, and so the names of the pharaohs needed to be chiselled off, and the ready mummies of the “evil” pharaohs also had to be smashed with hammers. This is how the names of the “evil” rulers were presumably erased from the memory of the people ([624], page 21). There are many such sepulchres with chiselled-off inscriptions in Egypt.

One must assume the mummies were also prepared and even dried in advance, so that they could be smashed later. But wouldn’t it be much easier to refrain from mummifying “evil” pharaohs altogether?

The style of this anecdotal legend gives away the epoch when it was invented – most likely, the XVIII-XIX century, which is when councils of judges appeared in Europe. This lackadaisical fairy tale appears to have been created immediately after the destruction of the inscriptions. It is also more or less clear who was responsible for this barbarity – Europeans conquered Egypt at the end of the XVIII century, during the famous Egyptian expedition of Napoleon. Prior to that, Egypt was governed by the Mamelukes. The “scientific processing” of Egyptian history must have commenced around this time. It is commonly known, for instance, that the artillery of Napoleon fired directly at the famous Sphinx in Gizah from cannons, and seriously mutilated its face ([380], page 77).

Why was it done? Could the ignorance of the French soldiers be the reason? However, it is known that a party of Egyptologists accompanied the Napoleonic army. Where were they looking? What was wrong with the face of the Great Sphinx and the lettering on the sepulchres? It must be emphasised that the rapid development of European Egyptology started with the Egyptian campaign of Napoleon – the decipherment of hieroglyphs, the discoveries of the papyri and so on, oddly combined with the destruction of the inscriptions on tombstones and cannons firing at the ancient monuments.

One cannot help suspecting that the authentic inscriptions on the ancient Egyptian tombs were getting in the way of the people who started to create (or, rather, alter) the Egyptian history around that time.

We must also remind the reader that many Egyptian artefacts were taken away to France, Britain and Germany in that epoch. This is how the compilation of the “ancient Egyptian history” began. Apparently, modern Egyptologists are wrong to blame the “ancient Egyptians” for these barbarities – the real culprits are the XVIII-XIX century Europeans.

11. Who destroyed the names of people, cities and countries written on the “ancient” Egyptian monuments? When was it done, and for what purpose?

And so, we are told that the names of the pharaohs as well as certain cities and countries found on many Egyptian monuments were chiselled off by someone, and even replaced in some cases. Egyptologists blame this on the “ancient Pharaohs”.

This is, for instance, what the Egyptologist Brugsch tells us about it: “When the kings of the 18th dynasty ascended to the throne, they started to destroy the monuments of the Hyksos dynasty, chiselling off their names and titles and replacing them with their own names and titles, giving birth to a complete travesty of historical truth” ([99], page 260).

But is it true that the Pharaohs are to blame? It goes without saying that a new regnant dynasty could destroy the monuments built by their predecessors for certain political reasons. However, the replacement of names with actual monuments left intact strikes us as thoroughly outlandish. For instance, the statue of F. E. Dzerzhinskiy was removed from a square in Moscow in 1991. Yet nobody came up with the preposterous idea of leaving the statue in its place and replacing the name of Dzerzhinskiy by some other name.

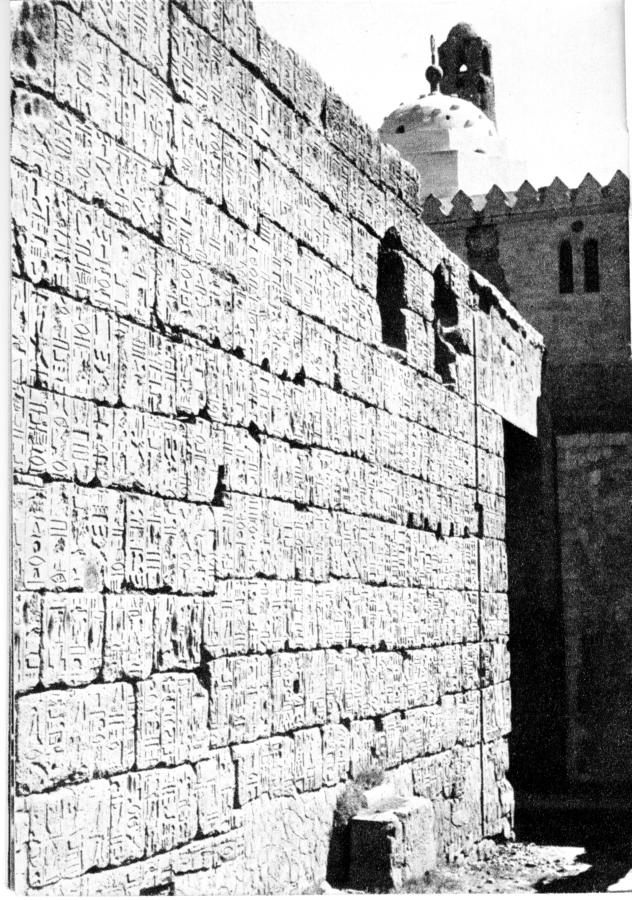

Moreover, we shall see that the destructions of names in Egypt was strangely selective. For instance, on the famous Karnak inscription ([99], pages 344-348) one sees a long list of cities conquered by Thutmos III. Certain city names, however, were chiselled off by someone in a number of places – we shall see that these names were very interesting indeed. What was wrong with them, and who is responsible for their destruction?

We shall voice our hypothetical explanation below. For the meantime, let us quote the words of N. A. Morozov, who also noticed this odd and significant fact.

“The inscriptions may have contained names pertaining to epochs considered too recent by the advocates of Egypt’s great antiquity, and some ultra-orthodox traveller may have chiselled them off so as they wouldn’t tempt anyone in the epochs when the interpretation of hieroglyphs wasn’t forgotten yet, or after 1822, right after Champollion’s reconstruction, when it was problematic for the Europeans to travel to Egypt, and to verify the information collected there critically”.

Morozov proceeds as follows: “I wouldn’t have dared to voice this consideration if it hadn’t been for a long memory of a certain Russian traveller’s report dating from the first half of the XIX century. I was completely flabbergasted, and remember this passage until this very day. To the best of my recollection, it comes from Basili’s book entitled ‘A Russian Sailor’s Voyage to Egypt, Syria and the Greek Archipelago’ published in the 1840’s.

The author says that when he visited the sepulchres and the buildings described by Champollion with a feeling of an almost religious piety, he discovered that numerous [sic! – Auth.] drawings reproduced in Champollion’s works had vanished without a trace. He asked his Arab guide about the identity of the parties responsible for this barbarity. The guide told him that the drawings were chiselled of by Champollion himself.

The sailor was amazed and enquired why Champollion needed to do it. The Arab, who had still remembered Champollion, answered laconically: ‘So that his books would remain the only document available to later researchers – to make them irreplaceable’ . . .”

Morozov sums up as follows: “The research of the names chiselled off the walls of the Egyptian monuments and their subsequent replacement inevitably lead us to the assumption that we are confronted by a deliberate mystification, which is likely to have been made by the first person to publish these inscriptions, especially given that the publication took place in the first half of the XIX century” ([544], Volume 6, page 1029).

We also have explicit evidence of eyewitnesses that virtually caught Champollion red-handed. This is what Peter Elebracht tells us in re the visit of Egypt by the architect Gessemer: “‘I had the ill fortune of coming to Thebes right after Champollion’ . . . This dire news concerning the state of affairs in the autumn of 1829 was brought by the Darmstadt architect Fritz Max Gessemer to his patron, Georg August Kestner (1777-1853), diplomat, collector and founder of the German Archaeological Institute in Rome . . . What did the ubiquitously glorified Champollion do?

Gessemer told Kestner the following: ‘I respect the scientific authority of Champollion in every which way, but I must say that as a person he demonstrates a temper that might greatly harm his reputation! The Theban sepulchre found by Belzoni was one of the best; at least, it was completely intact, without any signs of damage’.

‘And now, because of Champollion, the best objects that it had contained are destroyed. Beautiful life-size artwork lies shattered on the ground . . . Anyone who had seen this sepulchre before will not be able to recognize it now.

I was completely infuriated when I witnessed this sacrilege’” ([987], page 34).

The naïve Gessemer failed to realise what Champollion was actually doing. He made the simple-minded assumption (or, alternatively, received this information from a third party) that Champollion was driven by the vain desire to take the artwork away to France, hammering away at the ancient walls. Presumably, “two fragments of artwork were destroyed so as the third could be removed [? – Auth.]. However, it had proved impossible to cut the stone, and so everything perished as a result” ([987], page 34).

This “explanation” could be valid theoretically. However, given all that we know now, it is hard to chase away the thought that Champollion’s motivation was completely different.

According to some other evidence, when Champollion visited the Italian archive in Turin in 1824, he reportedly demonstrated a thoroughly different attitude towards the “ancient” Egyptian papyri. J. Posener, a French scientist, wrote the following about Champollion’s research of the Egyptian document in Turin in 1824: “Champollion . . . deals with numerous papyri . . . copying passages from the texts they contain, in particular, the dates and the names of rulers . . . Champollion has commenced his study of papyri fragments, treating them with the utmost care” ([964], pages 16-17).

Could the above be explained by the fact that there was no more pressing urgency to “correct” the ancient history? After all, we realise that in Europe this “editing work” had already been conducted by some of Champollion’s predecessors.

A propos, have all of the documents that were copied by Champollion in Turin with such great care survived until the present day?

The naïve idea about the destruction of inscriptions (and documents in general) in order to “make his copies the unique source for future generations of researchers” appears easy enough to understand. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the matter at hand bears no relation to mere vanity, mundane and understandable as it may be, and that Champollion’s motivation was a great deal more serious.

Our hypothesis is as follows. Apparently, somebody from the host of the first Roman Catholic missionaries of the XVIII century (or the Egyptologists of the XIX century) was deliberately destroying the vestiges of the authentic mediaeval history due to its being drastically at odds with the Scaligerian version, which had already been created in Europe.

Fortunately, the destruction wasn’t total, and many of the authentic artefacts have survived. Those materials (out of the ones considered dangerous for Scaligerian history) on the monuments of the “ancient” Pharaohs demonstrate that we are on the right track. As we shall see below, the history of the “ancient” Egypt is really the history of a part of the vast Russian Horde, also known as the “Mongolian” Ottoman (Ataman) Empire of the XIII-XVI century.

Such “dangerous materials” must have instantly been noticed by the first Catholic missionaries (Jesuits?), as well as a number of the Western European Egyptologists. They clearly couldn’t put up with it, given that in their European homeland similar memories of the Great = “Mongolian” conquest of the XIV century and the “Mongolian” Empire of the XIV-XVI century were already largely from history. Their phantom reflections were fortunate enough to survive, simply because they were shifted into deep antiquity owing to the error in the dating of the Nativity and therefore unrecognized. This is why they have escaped destruction.

In Egypt, the solution was perfectly easy. Civilised travellers armed themselves with hammers and chisels and started to destroy the priceless evidence of the ancient stones, methodically and ruthlessly, casting cautious thievish glances over their shoulders. They may have truly believed that they were improving an erroneous version of history – still, the scientific community would hardly recognise this as a valid excuse for their actions.

One must admit that these travellers managed to achieve their goal, and managed to alter history the way they wanted for a long enough period of time.

12. The condition of the “ancient” Egyptian relics.

It is believed that the “ancient” Egyptian priests were doing everything they could in order to protect the buried mummies of the great pharaohs from the “ancient” looters. It has to be admitted that their alleged “care” was manifest in a very odd fashion. First the pharaohs were buried with great fanfare, but then the priests would secretly take the mummies out and bury them in a new and secret place. This must have happened already in the XVII-XVIII century, after the dissolution of the Great Empire, when the “Mongolian” necropolis was no longer protected by the imperial authorities. The local priests may have waited for the restoration of the Empire for some time, but, having eventually realised that the process was irreversible, they decided to try and preserve the royal mummies.

At any rate, we are aware of the following: “Thus, for instance, in the epoch of the XXI and the XXII dynasty, all the mummies of Seknekra, Yakhmos, Amenkhotep I, Thutmos I, Thutmos II, Thutmos III, Seti I, Ramses II and Ramses III were concealed in a single place, as well as a number of Amon’s priests and several others that remain unidentified.

Apart from the mummy of Amenkhotep II, his tomb also contained the mummies of Thutmos IV, Amenkhotep III, Meneptah, Siptah, Seti II, Ramses IV, Ramses V, Ramses VI and Queen Teie, as well as two unidentified women and a child.

Small side-churches were also put to use in order to conceal the treasures, as in the case with the tomb of Amenkhotep II, where the researcher Lauré discovered and photographed a number of mummies that were simply piled together; one of the princes’ mummies even ended up in the ritual sepulchral boat of the tomb’s owner. We are unlikely to ever find out about the reasons for such great haste, or the crimes and the persecutions that preceded it” ([484], page 153).

Could it be that all of the events described above did not take place in “deep antiquity”, as historians are trying to convince us today, but rather the early XIX century, after the invasion of the Napoleonic army in 1798. The troops of the Egyptian Mamelukes were put to complete rout. This was followed by a bloody massacre – the Mamelukes were simply slaughtered en masse ([99]).

Most likely, the last Mamelukes and their priest were desperately trying to save at least some part of their halidoms from the invaders, hastily hiding mummies, treasures and so on. When the European victors and their allies drowned Egypt in blood, they obviously tried to eschew all responsibility for the destruction and the defacement of many monuments and point the blame at the “ancient Pharaohs”, “ancient looters”, “the ancient Hyksos dynasty” and so on – the usual wartime logic.

At the same time, we are told stories about “Napoleon’s respect for the holy places” ([484], page 81). His army was accompanied by “a large number of scientists, artists and writers . . . Napoleon himself claimed that he had invaded Egypt in order to ‘help it move towards the light’ . . . He had founded a number of special scientific institutions and gave orders to draw all the constructions and the ruins of monuments . . . Napoleon performed a great work in Egypt” ([484], pages 80-82).

An orifice was drilled in the Sphinx in order to find the passageways “mentioned in the antiquity. In Dendera he did what no other invader known in the entire history of humankind has ever done, leaving a precise copy of a large stone with the Zodiac as a replacement of the original, which was taken away to Paris” ([484], page 81).

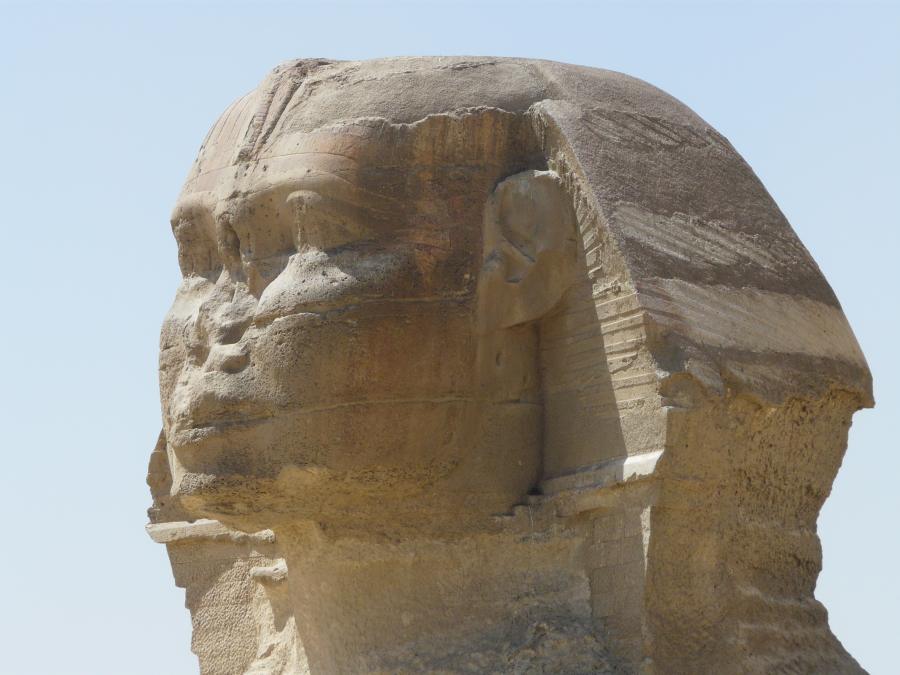

He ordered to open direct cannon fire in order to deface the ancient Sphinx ([380], page 77). The results can be seen in figs. 16.48, 16.49 and 16.50.

K. Keram obviously tries to mitigate the impression that the readers might get as he reports these barbarities committed by Napoleon’s soldiers: “One of the sphinxes lay there – half human, half beast, with remains of a leonine mane and holes in place of the eyes and the nose; Napoleon’s soldiers had once used his head as a target for their cannons. This beast was resting for many thousand years”, as Keram assures us, “and is prepared to lay there for many more millennia to come; it is so enormous that one of the Thutmoses could have built a temple between its paws” ([380], page 77).

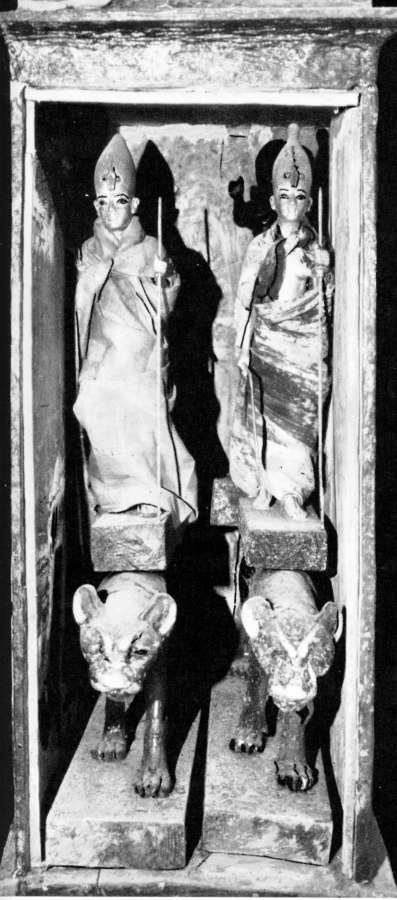

Will it be to bold to hypothesise that the French artillerists were also playing their part in the “rectification of history” at the request of one of the Egyptologists, destroying the symbols that did not fit into the “veracious” Scaligerian history of Egypt, such as a Christian cross on the head of the Sphinx, for instance? We have already mentioned that the shape of the Ureus snakes as seen on the headdress of the two “ancient” Egyptian sphinxes that were taken away from Egypt to St. Petersburg in the XVIII century and can be seen on the left bank of the Neva, roughly opposite the Hermitage, is indeed very similar to the Christian cross, qv in figs. 16.21 and 16.22. Also, the Ureus looks just like the Christian cross on the “ancient” Egyptian statues that can be seen in figs. 16.20, 16.51 and 16.52.

It might be that this semblance was too obvious in case of the Great Sphinx’s head . . .

Nowadays “the large cracks and indentations, especially on the face [of the Sphinx – Auth.] are filled with cement” ([730], page 37). However, even after this “restoration” the face of the Sphinx remains hopelessly mutilated.

Indeed, Napoleon performed a “great work” in Egypt, emphasising that the country needed assistance in order to “move towards the light”.

13. The advent of the mighty Mamelukes to Egypt.

In our research we shall be referring to the famous fundamental work of Heinrich Brugsch, the eminent German Egyptologist of the XIX century, entitled “History of the Pharaohs” ([99]), with comments by G. K. Vlastov. We follow Brugsch’s dynasty numeration, which is slightly different from the one suggested in [1447], for instance. This does not affect our results in any way at all.

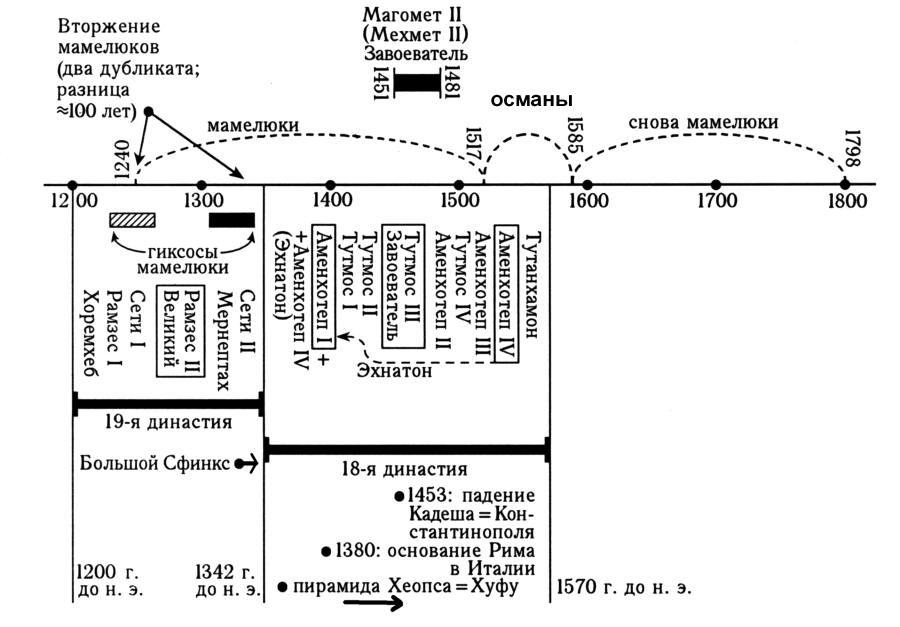

According to Scaligerian history, in the alleged year 1240 Egypt was invaded by the Mamelukes (see fig. 16.1).

13.1. The Mamelukes as the Cherkassian Cossacks. Scaligerian history admits that Egypt was conquered by the Cossacks.

The progeny of the Mamelukes is believed to be Cherkassian ([99], page 745). They were joined by other highlanders from the Caucasus on their way to Egypt ([99], page 745). We must note that the Mamelukes seized power in Egypt in 1250 ([797], page 753), in the heyday of the “Mongol and Tartar invasion”. This is when the Golden Horde invaded Egypt in Africa (in reality, this invasion took place about a hundred years later). See the Scaligerian map of the “Tartar and Mongol campaigns” in fig. 8.10. The Mamelukes and the Khans of the Golden Horde maintained close relations – they exchanged presents, the Khans of the Golden Horde married the daughters of the Egyptian Sultans, and so forth ([197]). In fig. 16.53 we see the Sphinx that was found during excavations conducted on the territories of the Golden Horde. Its wings broke off. Therefore, the Sphinxes had also been present in the culture of Russia, or the Horde, but this fact was eventually forgotten.

We already mentioned it in CHRON4 that the Cherkassians were really the Cossacks under yet another alias – this is reported by N. M. Karamzin, for instance ([362], Volume 4, page 323). Incidentally, this is why the city of Novocherkassk was the capital of the Don Cossacks. The fact that the Mamelukes are considered to have come from the Caucasus, or the borderlands of Russia, once again testifies that in 1240 A. D. (according to Scaligerian chronology) Egypt was invaded by the Cossacks.

13.2. The Caucasus and the Cossacks.

The very name Caucasus transcribes as KKZ unvocalized, and may therefore be derived from the word Cossack as well – its unvocalized root transcribes as KZK; we see a minor shift in the order of letters here.

Furthermore, the Mamelukes are said to have been an army of guards ([99], page 745) – just like the Cossacks.

Let us point out the excellent correspondence between the time of the Cossack Mamelukes’ advent to Egypt in Africa and the Scaligerian dating of the first wave of the Great = “Mongolian” Conquest, qv above. This is perfectly natural insofar as our reconstruction is concerned: the Mamelukes, or the Cossacks, came to Egypt as the “Mongolian” invaders, or the “Great Ones”. However, let us reiterate that the Great = “Mongolian” conquest really dates from the XIV century and not the XIII as the Scaligerian version declares.

13.3. The Cherkassian Cossack Sultans in Egypt.

The Mamelukes founded the Egyptian dynasty that reigned between the middle of the XIII century and 1517. The first part of this dynasty is usually referred to as Bagherit, and the Mamelukes are known as the Bakharits. After that, “between the years of 1380 and 1517 Egypt was governed by the Cherkassian Sultans” ([99], page 745; see fig. 16.1).

We can clearly see the aftermath of the centenarian chronological shift. The real Great = “Mongolian” Conquest of the XIV century was shifted 100 years backwards, to the XIII century. In reality, the first dynasty of the Cherkassian = Cossack Sultans in Egypt is the very first Cossack dynasty of the Mamelukes. The advent of the Mameluke Cossacks in the alleged year 1240 is merely a phantom reflection of their real arrival in Egypt that took place a century later.

The Cossack Mamelukes reigned in Egypt until 1517 (see fig. 16.1), and were replaced by the Ottomans (Atamans) for a brief spell (between 1517 and 1585 A. D.). However, in 1585 the Mamelukes come to power once again and reign up until the invasion of Napoleon into Egypt in 1798. A war breaks out. In 1801 the French withdraw from Egypt; however, in 1811 the Mamelukes are massacred ([99], page 746). Their power was finally crushed by Mohammed Ali in 1811 ([797], page 753).

It would be very interesting to find out about the fate of the Cherkassian Sultans after 1517. We haven’t studied this issue in detail; however, we must make an observation that brings the history of African Egypt even closer to that of Russia, or the Horde. Right about this time, in the XVI century A. D., the princely family of Cherkasskiy emerges in Russia ([193], page 217). “The Russian Cherkasskiy family belonged to the very cream of the ruling class” ([193], page 217). It is believed that the ancestors of the Cherkasskiy family were the Egyptian Sultans ([193], page 217). This is also reflected in their coat of arms, which is clearly “royal” in nature. We reproduced this coat of arms in CHRON4, Chapter 9. In the centre we see a royal orb surrounded by a red mantle adorned by mink fur and crowned by “the princely headdress, on top of which we see a turban – the symbol of the Egyptian sultans, the ancestors of the Princes of Cherkasskiy” ([193], page 217). See fig. 16.54.

Therefore, when the Egyptian sultans had a dire time and temporarily lost power in Egypt, a clan of their descendants appears in Russia and instantly joins the “very cream of the ruling class”. For instance, “Czar Ivan IV the Terrible was married to the Princess of Cherkasskiy” ([193], page 217). There is a Muslim crescent in their coat of arms, as well as the orb topped with a cross in the centre, and also a rider armed with a pike, a lion and two intertwined snakes placed vertically (see fig. 16.54). The latter symbol is very similar to the Serpent Column in Constantinople, which will be mentioned below. Let us also remind the readers that the Princes of Cherkasskiy were the owners of the Ivanovo village (nowadays a large city under the same name, which must be related to the famous Presbyter Johannes in some way, qv in CHRON5, Chapter 8:6.5.5.

From the formal point of view, the war between the Romanovs and Stepan Razin fought in the middle of the XVII century was de facto a war for the Russian throne between the Cherkasskiy clan and the Romanovs. Of course, the history of this war has been destroyed and obscured to a great extent over the years, but even the scarce shreds of information that we have at our disposal allow us to reconstruct the real events of that epoch, albeit roughly. Let us quote a single fragment in this respect; the quotation marks around the words “prince” and “lawful” simply reflect the fact that modern historians look at the events of that epoch through the prism of the Romanovian version.

“The Czar is referring to another Cherkasskiy – most probably, the young Prince Andrei, son of Prince Kambulat Pshimakhovich Cherkasskiy, a Kabardinian murza. Prince Andrei was baptised an Orthodox Christian; Razin took him captive after the conquest of Astrakhan. He must have played the part of Prince Alexei. Razin, as he moved up the Volga, took him along, placing the Prince on a separate boat that he ordered to upholster in red velvet. The “prince” was designed to serve as the symbol of the “lawful” ruler, which he did – against his will, of course. Inhabitants of the mutinous regions even swore fealty to him” ([101], page 119).

Despite having lost the war, the Cherkasskiy clan occupied a number of key positions in the imperial government of Russia up until the end of the XVII century ([101], page 218).

14. Linguistic connexions between Russia and African Egypt in the Middle Ages.

14.1. The alphabet used by the Egyptian Copts.

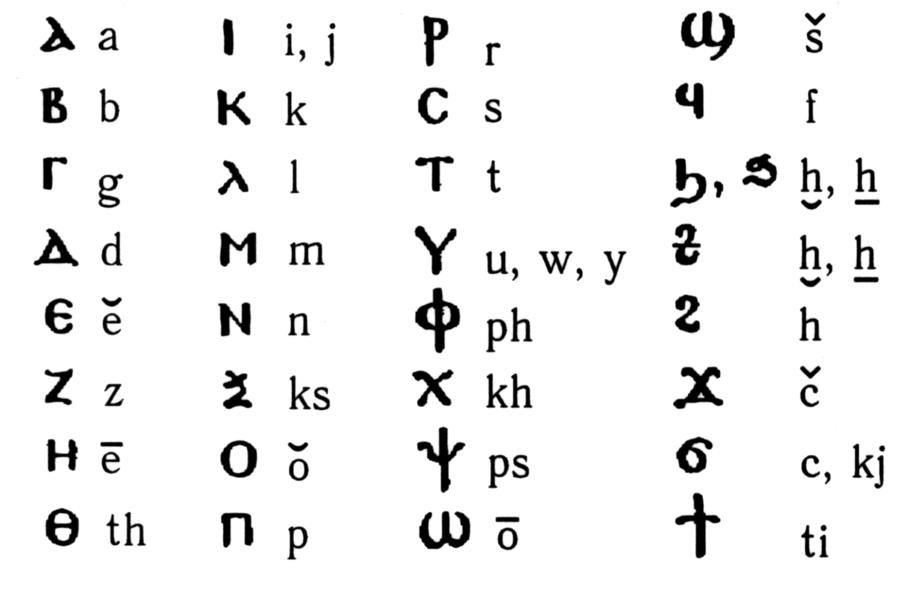

The Copts identify as the Christian populace of the mediaeval Egypt. According to Scaligerian history, Egypt was named after them (Copt = Gypt = Egypt, qv in [99]). We learn an amazing thing. “Coptic alphabet looks strikingly similar to Cyrillics . . . We believe that the Cyrillic alphabet was created under the influence of the Coptic” ([99], page 32).

We reproduce the Coptic alphabet in fig. 16.55. It is virtually identical to the Cyrillic alphabet. A similar table can be seen in the book of Nippert entitled “Alphabets of Eastern and Western Languages” (1859, Typography of the Imperial Academy of Sciences), and another one is included in the book of the Egyptologist H. Brugsch ([99], page 32).

Moreover, it turns out that the Copts were known as Kibt locally ([99], page 32). Could they identify as the Kitians (Scythians), as mentioned above? See also Part 6 of the present book.

Our conception explains this fact instantly – some descendants of the Cossacks, or the Great = “Mongolian” conquerors of the XIV century must indeed have remained in Egypt.

14.2. Egyptian names in Russia.

The scientific almanac ([964]) contains a linguistic work of N. A. Meshcherskiy under the fascinating title of “Egyptian Names in the Slavic and Russian Menaions” ([964], pages 117-126).

N. A. Meshcherskiy reports the following: “The ancient Slavonic and Russian . . . languages pertained to . . . the Eastern group . . . of Christian languages, which was born . . . in the countries of the European Southeast, the Middle East and the Northeast of Africa. The centre of this cultural and historical region was . . . the Greek world (. . . or Byzantium), with its common Greek language of Koyne; the periphery . . . also comprised such languages as Coptic and Ethiopian in the South, Syrian, Armenian and Georgian in the East, Gothic, and, finally, ancient Slavonic in the North and the Northeast. The ancient Slavonic . . . language . . . also branched into . . . the ancient Russian version of Church Slavonic, as well as the Bulgarian and Serbian versions of the same language; they were also joined by the ancient Romanian branch of the language used in Moldavia and Walachia in the XIV-XVII century.

Constantly renewing economical, political and cultural ties between the nations that spoke and wrote in the languages listed above led to their close interaction for the duration of the entire mediaeval period . . . Such contacts between languages are most clearly traced in the onomastic field, and particularly in the domain of personal names” ([964], pages 117-118).

Meshcherskiy’s postulations are in perfect concurrence with our reconstruction. The XIV century, which is when the Great = “Mongolian” was formed, the Slavic language spread all across its territory, beginning to affect the local languages. As we can see, the result was a formation of a single cultural and historical circle, as the linguists cautiously put it.

By the way, where is the “Mongolian” language spoken by the “Mongolian” conquerors? We don’t see a trace of it anywhere for obvious reasons – it was simply another name of the Russian language.

N. A. Meshcherskiy cites many examples of Coptic = Egyptian names found in the Russian holy books ([964], pages 120-125). Among them we find the following:

Ammon (Ammun) – 26 January, 1 September, 4 October.

Varsanoufiy – 6 February, 29 February, 14 March and 4 October.

Isidore, clearly a derivative of Isis, the name of an Egyptian goddess – 4 February.

Manefa – the female version of the name Manethon, according to N. A. Meshcherskiy – 13 November.

Moisey (Moses) – 28 August and 4 September. “This name must have initially been the ancient Egyptian word for “child” (msj). The erroneous etymology must owe its existence to the ancient Hebraic language” ([964], page 122). One must recollect the existence of the words “masenkiy” and “masetka” in the Russian language, which translate as “baby” (“child”), qv in Dahl’s dictionary ([223], page 786). The name Moses sounded as “Mosiy” in Russian, which brings it even closer to the abovementioned words. Such coincidence between the Russian and the “ancient” Egyptian words for “baby” can hardly be of a random nature.

Sennoufriy – 25 March. “This must be the famous Coptic name Shennoute, translating as ‘Son of God’. It was one of the most common Coptic names since its first bearer was the inventor of the ascetic Coptic alphabet” ([964], page 124).

The name is obviously a combination of two words, the Russian “syn” (“son”) and the Greek “theos” (“god”). Therefore, one of the most common Coptic (Egyptian) names contains a Russian root. Initially, the name must have referred to Jesus Christ, and then erroneously attributed to the “inventor of the Coptic alphabet”, transforming into a regular name. The same happened to the name Vassily, a derivative of the Greek word for “king” – “basileus”.

N. A. Meshcherskiy concludes with the following passage: “Thus, almost forty names in the Slavonic and Russian . . . fund unite the history and culture of the Russian nation with those of the ancient, or pre-Christian [as Meshcherskiy believes – Auth.], and also the Coptic (or Christian) Egypt . . . This is a relic of ancient cultural and historical ties” ([964], pages 125-126).

Meshcherskiy regretfully points out the following circumstance as he writes about the connexion between the Russian and the Egyptian language: “The Egyptologists have barely considered this issue at all” ([964], page 120). This is perfectly understandable. As is the case of the Etruscan inscriptions, it is very unreasonable for a researcher to discover links between the Slavic languages and the “classical languages of the antiquity” – one may well recollect the fate of F. Volanskiy, qv in CHRON5, Chapter 15:12.5.

Let us conclude with the reminder that, according to the “ancient” myths, the souls of the dead were transported to the underworld across a great river by the boatman Charon. We have already voiced the idea that it may be a reference to the transportation of the dead across the Mediterranean in the XIV-XVI century for their subsequent burial in the imperial “Mongolian” graveyard in Egypt, primarily the deceased Czars, or Khans, from Russia (the Horde) and the Ottoman (Ataman) Empire. We suggest that the name “Charon” may be a derivative of the Russian word “khoronit” – “to bury”.

One must also note that in this case the name Pharaoh (still spelled with a “PH”) may be derived from the Russian word for “burial”, which is “pokhorony”. In other words, a Pharaoh is a buried Czar.

15. The confustion between the sounds R and L in Egyptian texts.

According to H. Brugsch, the “ancient” Egyptians frequently confused the sounds R and L for one another. For instance, the name of the nation Rutennu was also pronounced as Lutennu ([99], page 243). One must remember about the frequent flexion of the sounds R and L if one conducts a research of Egyptian history (as a matter of fact, it is also typical for the Chinese language). We shall be confronted by this phenomenon quite a few more times; Egyptologists are well aware of it.

Let us make a brief digression here. If we are to consider the confusion of R and L, the name of the famous city of Jerusalem transforms into Je-ROS-RIM, or ROS-RIM (RUS-RIM) – Russian Rome, in other words. There is nothing surprising about this fact according to our conception, since the names of Jerusalem and Russia are no longer separated by millennia and the abyss of cultural differences. They may well be in some relation, stemming from the same root or some such.

16. “Ancient” Egyptian texts were often transcribed in consonant letters exclusively.

In CHRON1, Chapter 1:8.1, we already quoted the words of a modern chronologist: “The names of the [Egyptian – Auth.] kings are also given in a perfectly arbitrary (the so-called “scholarly”) rendition, common for the university textbooks on the history of the ancient Orient. University students read Egyptian texts void of vowels in this very manner. These forms often differ from one another to a great extent, and it isn’t possible to arrange them into any system, since they all result from arbitrary interpretations that became traditional” ([72], page 176).

Therefore, Egyptian names were transcribed as strings of consonants sans vowels. Therefore, the vowels that they contain are of no importance to a researcher, since they were added arbitrarily by the modern commentators.

17. A scheme of our reconstruction of Egyptian history.

In fig. 16.56 we reproduce a very general chronological scheme of Egyptian history in our reconstruction, starting with the XI century.

1) Nothing appears to be known about the epoch that predates the X century. No documents have survived from those days – possibly, due to the non-existence of literacy.

2) The period of the X-XII century A. D. is covered very sparsely – in the translated Egyptian texts at least. Therefore, we shall refrain from considering that epoch presently. Its history is legendary and nebulous to a great extent.

3) The period of the XIII – early XIV century A. D. is covered somewhat better. As we have discovered, it is described in the sources that the Egyptologists date to the so-called 19th dynasty of the pharaohs. They made the erroneous suggestion to date it to the XIII century B. C. approximately ([1447], page 254). A “mere” twenty-five centuries earlier than our suggested dating, that is. Still, given the fluctuation range of two or three millennia, which is very common in Egyptology, qv above, this isn’t an outrageously great period.

4) The period between the first half of the XIV and the end of the XVI century contributed to the history of the “ancient” Egypt the most. Many key events of Egyptian history are concentrated here. It has to be said that Egyptian history is hardly an exception in this case; the epoch of the XIV-XVI century suppresses earlier historical periods in the history of other regions as well (judging by the surviving documents).

This is the epoch of the Great = “Mongolian” conquest and the formation of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire. The great conquest of the XIV century A. D. has apparently become reflected in the history of the “ancient” Egypt as the so-called 14th dynasty of the pharaohs – the Hyksos dynasty. Egyptologists date this epoch to 1786-1570 B. C. Amazing precision, isn’t it? The error margin equals one year here.

The events that came in the wake of the Great = “Mongolian” conquest of the XIV century are reflected in the history of the “ancient” Egypt as the history of its famous 18th dynasty. Egyptologists date it to 1570-1342 B. C.

5) The period between the end of the XVI century and 1798. First we have the Ottoman reign, which ends in 1585, and then the second dynasty of the Mamelukes. It is concluded by the Napoleonic invasion of 1798.

6) Egypt was an important religious and cultural centre of Byzantium in the XI-XIII century, and then the “Mongolian” Empire of the XIV-XVI century. It was the location of the central imperial cemetery of the “Mongols”. This is where numerous chronicles were written – some of them carved in stone, qv in fig. 16.57, for instance. They didn’t so much refer to the history of Egypt in Africa as to that of the entire Great = “Mongolian” Empire, which had covered enormous territories, including the Far East and the Americas. One must also bear in mind that many hieroglyphic texts of the “ancient” Egypt still haven’t been read or translated, as discussed in CHRON4, Chapter 20:5.4.