Part 5.

Ancient Egypt as part of the Great “Mongolian” Ataman Empire of the XIV-XVI century.

Chapter 18.

The XIV century “Mongolian” invasion into Egypt as the Hiksos epoch in the “ancient” Egypt.

1. The identity of the “ancient” Hiksos dynasty.

Scaligerian history is of the opinion that in the alleged year 1786 B. C. armies of foreign invaders stormed into Egypt. The foreign Hiksos dynasty came to power as a result ([1447], page 254). They ruled in Egypt for 200 years ([1447], page 254). Their reign is considered “a dark age in Egyptian history” and also “the period of foreign rule in Egypt” ([99], page 238).

1.1. Were the Hiksos simple shepherds?

Brugsch reports the following, quoting from Manethon: “Their entire nation was known as Hiksos, or ‘shepherd kings’” ([99], page 239). Egyptologists must have interpreted Manethon’s words literally, since they call the representatives of the Hiksos dynasty “shepherd kings” customarily, apparently believing that these monarchs could trace their ancestry to real shepherds who had once chased herds of sheep across meadows and later decided to become kings in Egypt.

N. A. Morozov wrote the following in this regard: “Having first learnt that the fourteenth Egyptian dynasty was the dynasty of shepherd kings – from Eusebius, I think, the first thing I checked was whether other pages of his work might contain any information about dynasties of grooms and tailors – however, none such were mentioned anywhere . . .

Further acquaintance made my amazement even greater. Joseph Flavius explains that “according to some chronicles they were Arabic nomads, whereas others refer to them as to shepherds taken captive.

Shepherds, and captive ones, at that, as though Egyptians didn’t have any shepherds of their own to crown as their kings in solemnity!” ([544], Volume 6, page 894).

N. A. Morozov makes the justified assumption that under “shepherds” the author really understands Christian priests. This instantly makes us think of the “kingdom of Presbyter Johannes”, one of the mediaeval names for Russia, or the Horde. Indeed, N. A. Morozov points out that one of the last “shepherd kings” was “Ases, according to Flavius (Table LXVI, Column 1), which is identical to the Latin “Jesus” and the old Russian “Isus”. We see that in the book of Sophis he is indicated as a representative of a separate dynasty, while Flavius calls him “JOHANNAS”, which must be the Greek version of ‘Johannes’” ([544], Volume 6, page 896).

Below we shall demonstrate that the “shepherd king”, or Presbyter Johannes, appears in the history of the Hiksos dynasty for a good reason. The epoch of the Hiksos rulers in the history of the “ancient” Egypt is most likely to be identified as the epoch of the Great = “Mongolian” Conquest of the XIV century, when the Horde of Batu-Khan = Ivan Kalita = Presbyter Johannes (or one of his descendants) conquered Egypt, alongside a great many other lands, and founded the royal dynasty of Egypt, initially considered “foreign” by the locals.

1.2. The Avars and Ruthenia (Russia, or the Horde).

Brugsch describes the conquest of the “ancient” Egypt by the Hiksos invaders as follows: “According to Manetho . . . there was a time when a barbaric and savage nation from the Orient swarmed all across the lower lands and conquered the entire country without meeting much resistance from the part of the Egyptians . . .

Then they made one of their ilk King. His name was Salatin, or Saltis, and also Silitis [or “Sultan” – Auth.] . . . Having discovered a city in the Setroit District . . . known as Avaris, he fortified it with tall walls and quartered a garrison of 240.000 heavily armed warriors there” ([99], pages 238-239).

Brugsch reports that the homeland of the Hiksos was known as Syria, Asher, Menti and Oriental Ruthennu, the latter name being the most ancient ([99], pages 242-243).

Apart from that, when Brugsch comments the mention of “Ruthen shepherds” in one of the “ancient” Egyptian inscriptions, Brugsch tells us that this expression gives us a hint concerning “the origins of the shepherd kings that ruled in Egypt” ([99], page 352). The fact that Ruthenia was another name of Russia, or the Horde, is mentioned in Part 6 and in [517].

Thus, Egyptologists themselves de facto tell us that the Hiksos dynasty came from the East of Russia, given that “Ruthenia” was an alias of the Horde, as we have mentioned quite a few times. This explains the name of their “new” capital in the “ancient” Egypt – Avaris ([99], pages 238-239). The Avars were “a union of tribes, predominantly Turkic . . . in the VI century they founded a Kaganate in the Danube region” ([797], page 12).

Let us note that prominent Egyptologists “Rouget, Mariett and Laut believed Avaris to identify as Tanis” ([99], page 272). Thus, the name Tanis, or Tanais (Don) is closely linked to that of Avaris.

Later, after the Great = “Mongolian” Conquest, and also due to the erroneous “implantation” of geographical names from old documents, all the names such as “Tanais”, “Sarmatia” (or “Samara”), “Goths” etc spread all across the world and wound up abroad. Then their Horde origins were forgotten and became ascribed to the locals.

Historians even refer to the “Avaro-Slavs” as to “conquerors of Europe” – Falmereier went so far as to assume that the Avaro-Slavs “have slaughtered the entire populace of the ancient Greece” ([195], page 41).

According to Orbini, “King Agilulf declared a war upon the Romans . . . and set forth from Milan to seek assistance of the Kagan, the Avar ruler, who sent him an army of the Slavs” ([617], page 25). Also: “The Slavs . . . signed a pact with the Huns and the Avars and invaded the land of the kingdom [Greece – Auth.]” ([617], page 19). Further: “The Kagan is the king of the Avars, likewise the Slavs” ([617], page 33).

1.3. The Hiksos Cossacks bring horses to Egypt.

E. A. Rogozina tells us the following: “The Egyptians hardly had a reason to be grateful to the Asian conquerors [the Hiksos – Auth.]. Nevertheless, the latter did give a priceless gift to the Egyptians, since they were the ones to bring horses to Egypt. Despite their paramount importance, these domesticated animals weren’t known in the Nile delta. There were many graphical representations of asses, which were used for many agricultural purposes, but none of horses . . . The equine population became acclimatised and started to grow” ([730], pages 112-113).

Everything appears to be correct. The Hiksos Cossacks had ridden horses since times immemorial; it is therefore natural that they brought the culture of horsemanship to Egypt. The famous Arab horses may have originated in this manner.

1.4. The names of the Hiksos kings.

According to our reconstruction, the “Mongolian” invasion of the XIV century was Russian and Turkic for the most part, hence the advent of the Avars to Egypt and the foundation of the city of Avaris. As for the name “Hiksos”, it is beginning to resemble the well familiar “Guz”, or “Cossack”, qv in CHRON4. Could the name of the famous field filled with graves and pyramids be of a similar origin (Gizeh, or Giza)? The name is once again similar to the word “Cossack” ([99], page 748).

Brugsch cites the names of the first six Hiksos kings ([99], page 239). We have already mentioned one of them – Salatis, or simply “sultan”.

The name of the second is “Bnon, or Banon, or Beon” ([99], page 239). It might well be the ancient Russian name Boyan (or Bayan), which is still popular in Bulgaria.

The next Czar is called Apahnan (Apa-Khan, in other words) – see [99], page 239).

Next we have Aphobis or Apophis.

The next one is very explicitly called Annas, or Iannias (Ianas) – see [99], page 239. This is clearly “Johannes”, or “Ivan”.

Finally, Aseph (or Aseth). Asaf, in other words – a famous Russian name whose full form is “Ioasaf” (Jehoasaph).

1.5. Phoenicia vs. Venice. The Slavs and the Veneds.

Yet another link between the Hiksos and the Slavs is the fact that the Hiksos came from Phoenicia, according to the Egyptologists themselves ([99], page 242). And, as we already know, the “ancient” Phoenicia (or Vinicia) was named after the Vened Slavs – hence the mediaeval name “Venice”, as well as the Slavic word “venets” – “crown” or “diadem”.

Brugsch reports the following: “The old homeland of the Phoenicians lay to the west . . . up until the city of Tsor-Tanis” ([99], page 242). This is obviously “Czar-Tanais”, or “Czar-Don”. Therefore, Scaligerian Egyptology basically claims that the “ancient” Hiksos, or Phoenicians, had once lived in the vicinity of Tanais, or the Don – right where we find the Don Cossacks, in other words.

1.6. The “ancient” Egyptian “sutekhs” as the Russian judges “sudia”.

Let us continue. The Hiksos monarchs “revered . . . the son of Nuit, the celestial goddess – a god called Seth or Sutekh with the alias of Nub – “gold”, or “golden” ([99], page 244). This is clearly a reference to Jesus Christ – Son of God and the Judge of Heaven and the Earth. “Sutekh” is a corruption of the Russian word “sudia”, which stands for “judge”, and gold always accompanies the icon representations of Christ.

Incidentally, the “ancient” Egyptian Sutekh is believed to be a Canaanite god ([99], page 448). This is quite in order – the god of judgement was really a god of the Khans, or, rather, the god of Russia (the Horde), which was ruled by the Khans.

All of the above leads us to the following natural hypothesis. The “ancient” Hiksos monarchs can be identified as the same old Mamelukes, or the Cossack conquerors of Egypt dating from the first half of the XIV century A. D. Scaligerian history misdates the advent of the Mamelukes by roughly a hundred years, believing it to have taken place earlier, in the middle of the XIII century A. D.

Since the Mamelukes were Cossacks, it is perfectly legitimate to call them “Cherkassians” ([99], page 745).

2. Why the names of nearly all the Hiksos = Cossack kings happen to be chiselled off the monuments of the “ancient” Egypt.

Brugsch reports the following: “The names of the Hiksos monarchs inscribed upon their monuments (statues, the Sphinxes etc) as well as the monuments of the “ancient” Egyptian kings [the implication being that the Hiksos left their graffiti on other monuments but their own – the monuments of the “ancient” rulers, that is – Auth.] have been chiselled off everywhere, completely or partially, and it is exceptionally difficult to read them by the meagre vestiges preserved on the monuments” ([99], pages 245-246).

Keeping all of the above in mind, it will hardly be too bold an action to name the industrious worker of the hammer and chisel – the avid corrector of the “ancient” history. He must have exercised with the chisel in the mornings, and written the “ancient” history of Egypt in the evenings, tired of the hard menial labour.

3. The famous Great Sphinx on the Gizeh Plain was built by the Hiksos (the Mamelukes).

According to Brugsch, “the foreigners [the Hiksos – Auth.] adopted the official language of the Egyptians and their holy writing together with the Egyptian customs and traditions” ([99], page 244).

Further also “In the cities of Tsoan and Avaris the foreigners built sublime temples to honour this god [Sutekh, or the Judge – Christ, in other words – Auth.] and also constructed a plethora other monuments, the most remarkable ones being the Sphinxes” ([99], page 245).

Vlastov adds: “The monuments dated to the epoch of the Hiksos are as follows:

1) The Sphinxes (upon whose shoulders we find the legend ‘Apopi, beloved by Seth’) with severe features that don’t look very Egyptian,

2) The granite group in the Boulak museum, unsigned . . .

3) There is also the head of one of the shepherd kings in the museum of Bulak” ([99], page 245).

Brugsch writes: “A characteristic figure of this new, adopted artistic manner is the winged sphinx” ([99], page 245).

Thus, Egyptologists are telling us themselves that the Egyptian sphinxes were built by the Hiksos, and also that this culture was brought to Africa from afar. The inscription as seen on the shoulders of some statues is most likely to stand for the well-known Christian formula: "Pope, beloved by the Lord and Judge", or "Pope beloved by Christ". Incidentally, the Orthodox Patriarch of Alexandria in Egypt is still known as the Pope ([83], Volume 3, page 237). V. V. Bolotov writes the following in this respect: "The future Patriarch of Alexandria . . . was usually . . . called Pope in Egypt" ([83], Volume 3, page 237).

The head-dress worn by the Sphinx is the same as the headscarf worn by the Orthodox patriarchs to this day.

According to Brugsch, the name Apopi (or Aphophi) "is very similar to the name of the Shepherd King Apophis . . . who was the fourth monarch in the Hiksos dynasty according to Manethon's legend" ([99], page 246). However, "Pope the Shepherd" is a blatantly mediaeval Christian term. Also, the name of the first Hiksos monarch contains the word "Apopi" (or "Apopa") - see [99], page 246. "Pope", in other words. Therefore, the Christian inscription saying "Pope the Spiritual Leader" that we find on certain sphinxes ceases to be surprising.

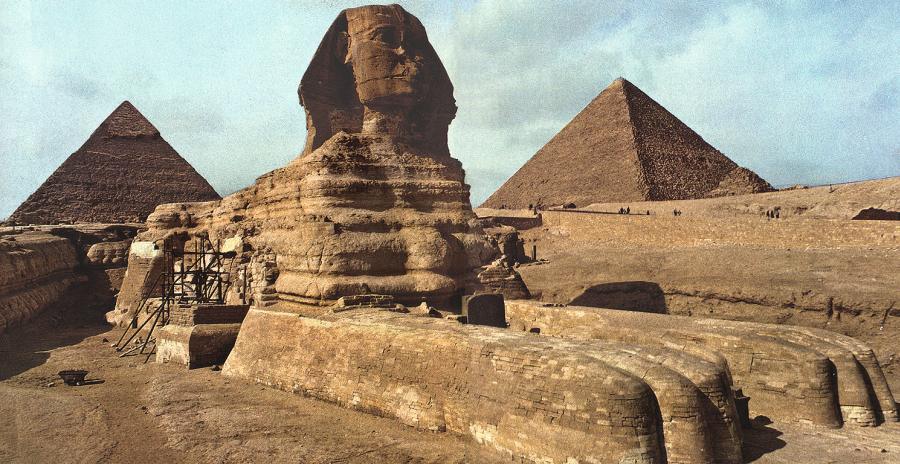

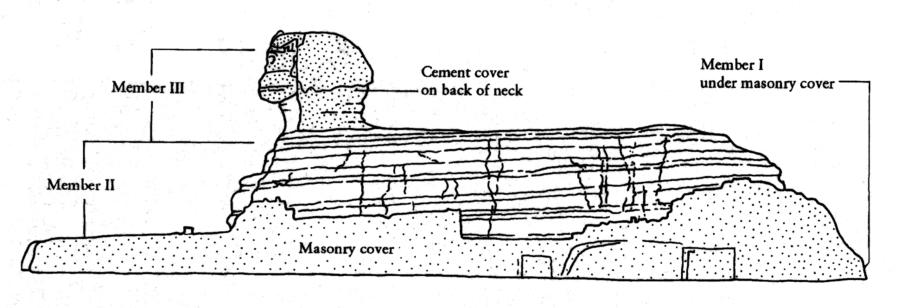

Furthermore, the most impressive of all sphinxes - the Great Sphinx that stands next to the Pyramids "represented the four elements as the ox, the eagle, the lion and the human" ([484], page 41; see fig. 18.1). Let us remind the reader that the Great Sphinx is believed to be the oldest construction of the "ancient" Egypt. In fig. 18.2 we see a schematic section view of the Sphinx; it is plainly visible how the Egyptian builders treated a rock and put stone blocks all around it to make it look like the Sphinx.

However, the symbols of the ox, the eagle, the lion and the human are considered to be symbols of the Evangelists, no less! This is what we learn from the "Christianity" encyclopaedia: "The usual symbol of the four Evangelists was the mystery chariot [or a creature known as the Cherubim - Auth.] . . . consisting of four creatures that resemble a human, a lion, an ox and an eagle. These creatures have become individual emblems of the Evangelists: . . . Christian art depicts Matthew accompanied by a human (or an angel), Mark with a lion, Luke with an ox and John with an eagle" ([936], Volume 1, page 513).

It turns out that the Great Sphinx at Gizeh united all these Christian symbols of the Evangelists into a single gigantic sculpture. What exactly is the symbol, then?

It is the well familiar Christian Cherubim. Indeed, the Cherubim has four faces - human, leonine, aquiline and bovine. This is known perfectly well from ecclesiastical tradition. For instance, this fact is mentioned by Theophilactus, Archbishop of Bulgaria, in his "Gospel Annotations" ([74], page 179). The name Cherubim is found in the Bible (the prophecy of Ezekiel, for example), but is also translated as "chariot", qv above.

Therefore, a Cherubim is precisely the creature described above, which combines the features of a human being, a lion, an ox and an eagle. It occupies one of the primary places in Christian symbolism.

"The Cherubim are blessed to be particularly close to the Lord . . . The supreme position of the Cherubim in the angelic world is also indicated in certain passages from the Holy Writ, which claim the Lord to be sitting on a Cherubim . . . The Cherubim are surrounded with a host of saints and angels in heaven; . . . the latter are subordinate to the Cherubim (Revelation 15:7). Being so close to the Creator, the Cherubim reflect the unapproachable greatness of the Lord and his glory (Hebr 9:5)" ([936], Volume 3, page 157).

Thus, what one sees in the Gizeh pyramid field as the Great Sphinx is really the famous Christian symbol, or the Cherubim. Nearby one finds numerous other Cherubim, or sphinxes that form the Sphinx Alley.

The site of the Great Sphinx also wasn't chosen randomly: "The gigantic head of the Sphinx is visible among the sepulchres - it must be one of the oldest monuments in this ancient graveyard" ([99], page 749). Therefore, the Great Sphinx stands on a Christian graveyard, which is the Gizeh field near Cairo, full of pyramids and graves.

What do the Egyptologists know about the Great Sphinx today? They write the following: "The Sphinx is one of the most remarkable ancient artefacts, and is most likely to be the guardian on the oldest graveyard of the world known to us today - the Gizeh Field of Death" ([99], page 754).

Let us reiterate that the word "Gizeh" is most likely to be a derivative of the word Kazakh (Cossack), or Gus (Hiksos) - the Cossacks once again.

The Sphinx is "a leonine figure with a human head; the lion is facing the East and has its paws stretched out before it . . . No rooms or chambers were discovered anywhere inside the Sphinx; its body was carved from a whole natural rock" ([99], page 754). The ancient sculptors used masonry in order to compensate for the uneven shape of the rock, qv in fig. 18.1.

"The side of the rock that faces the East wasn't cut down; its protruding part was artfully transformed into a head with a beard and a ureus . . . There are traces of red paint [? - Auth.] that once covered the Sphinx . . . One finds it hard to answer the numerous questions one feels inclined to ask when one contemplates this amazing work of art" ([99], page 755).

The very word "ureus" (royal snake often depicted crowning a pharaoh's head) may also be derived from the word "russkiy" ("Russian") - RSSK unvocalised; it must have transformed into the Latin "Rex" eventually.

Egyptology believes the Great Sphinx to be older than the three great pyramids of Egypt. As we shall see below, the Egyptologists are probably right. Apparently, "King Khufu [the creator of Egypt's largest pyramid - Auth.] believed it [the Great Sphinx - Auth.] to be a holy relic of the antiquity . . . The Sphinx remains an enigma to this very day" ([99], page 755).

We hope that the New Chronology might shed some light over this mystery.

And so, our theory can be broken down as follows:

1) The Cherkassians, or the Mameluke Cossacks that came to power in Egypt in the middle of the alleged XIII century B. C. can be identified as the famous Hiksos dynasty from the "ancient" Egyptian history. The Hiksos invasion appears to be yet another reflection of the Great = "Mongolian" Conquest of the XIV century.

2) This is the very time when the Great Sphinx was erected in the Christian burial ground of Gizeh as the Christian symbol of the Cherubim - the XIV century of the new era. This field became the site of the central funereal complex of the entire Great = "Mongolian" Empire.

Vague recollections of winged sphinxes survive in Russian and in other languages as legends of the Phoenix. "Sphynx" and "Phoenix" are basically the same word, the latter being a vocalised version of the former, with the characteristic Russian omission of the first letters in the abbreviation of names (cf. "Kolya" and "Nikolai", "Lyosha" and "Alexei" etc).

Above we have already voiced the idea that the Phoenix is a legendary image of the Emperor, embalmed and taken away to Egypt for the funeral. The Phoenix must be the same creature as the legendary Rukh bird. Another thing that comes to mind in this respect is the fact that the Egyptians worshipped the god Horus ([650], page 10), depicted as a bird. "The solar god, or Horus, was considered the protector of a king's power. He was worshipped in the form of a falcon" ([464], page 89). "Rukh" may be a reversed reading of "Horus" - the latter name, in turn, is most likely to be closely linked to the name "Christos".

4. Egyptologists are uncertain about the correctness of the "ancient" Egyptian names in their translation.

One may have expected the modern Egyptologists to be capable of translating the "ancient" Egyptian names unambiguously. Unfortunately, this isn't always the case. For instance, the famous Egyptologist Shabas translates one of the hieroglyphs as "hyaena", whereas Brugsch, another eminent authority, believes the translation to be "lion" ([99], page 526). The two animals differ from each other greatly.

Let us continue. "Here Shabas reads the phrase as 'you make a hole in the fence to gather some fruit' etc instead of translating it as 'you open your mouth' etc" ([99], page 527). These two "translations" have absolutely nothing in common. One gets the suspicion that both may be incorrect. Let us continue.

For example, Brugsch offers a translation of the inscription found on the sarcophagus lid of the famous Pharaoh Mencaur, the creator of the third largest pyramid. The sarcophagus is kept in the British Museum. Even Vlastov, Brugsch's faithful translator and commentator, is outraged.

"It must be admitted that we utterly fail to comprehend why Brugsch uses Classical names instead of the names of Egyptian deities. 'Olympus' [in Brugsch's text - Auth.] is translated by Maspero as 'heaven', 'Urania' stands for the goddess Nuit, and Kronos is used in lieu of Sebh" ([99], page 136).

What could all of the above possibly mean? Do the Egyptologists actually read the "ancient" Egyptian inscriptions, or do they merely offer us tentative translations? Olympus is a far cry from "heaven", after all, and Urania definitely isn't the same goddess as Nuit. There is nothing in common between the names "Kronos" and "Sebh", either. Such tendentious replacement of names changes the very spirit of the text in a most drastic manner, affecting its perception and the whole picture of the "ancient" Egyptian life in general.

Brugsch points out the following fact: "Hieroglyphs are read in the direction faced by the figures - from the right to the left, or vice versa, or even from the top to the bottom" ([99], page 25).

It would be expedient to cite the opinion of Y. Perepyolkin in re the translations of the "ancient" Egyptian names here. In the foreword to his voluminous book entitled "The Revolution of Amen-Khotep IV. Part I" he informs the reader of the following:

"Readers might be confused about the uncommon renditions of Egyptian names. The present book attempts (possibly, with errors) to replace the customary and yet inconsequential and often outright arbitrary renditions of the ancient Egyptian names by other versions, possibly not ancient (this is hardly a feasible task), but yet authentically Egytian - namely, Coptic, or Saidic, to be more precise.

Therefore, instead of the customary names of cities and places, which are usually Greek and Arabic, their Coptic equivalents were used. Thus, instead of "Luxor", "Memphis", "Thebes", "Iliopolis", "Phayum", "Asun", "Siuth", "Esne", "Medineth-Abu", "Akhmim" and "Hermopolis" the book refers to "Apeh", "Mentheh", "Neh", "On", "P-Yom", "Sven", "Syovt", "Sneh", "Chemeh", "Shmin", "Shmun" etc . . . The names that I haven't managed to vocalise are of a tentative nature" ([650], pages 5-7).

What do the names "Hermopolis" and "Shmun" have in common? Or "Luxor" and "Apeh", or "Iliopolis" and "On", for that matter? The rest aren't any better, with the sole possible exception of Memphis.

The name Aton is encountered in virtually every "ancient" Egyptian text. It turns out that Y. Y. Perepyolkin believes this reading to be incorrect, suggesting "Yot" as a viable alternative. Incidentally, one of the consequences is the transformation of the name Ekhnaton, which we shall discuss at length below, into Ekh-Ne-Yot, or simply "Ignat" ([650], page 7).

Let us summarise. Could this mean that the vague and variable interpretations of certain "ancient" Egyptian names, stubbornly called "translations" today, are largely arbitrary and even subjective, which is very dangerous indeed.

If this is indeed the case, one must say so outright and publicly - not just in specialised works such as the book of Y. Perepyolkin as cited above, but in front of a large audience in order to cease the practice of presenting one of the many possible vague interpretations of an old text as doubtlessly "final", let alone "scientific".

If one were to make such a frank and public declaration, it would provide us with an opportunity to read the old texts anew, from a different viewpoint, and possibly more correctly. The New Chronology suggests many such alternatives.

For instance, Brugsch translates the name "Menes" as "firm or standing fast" ([99], page 117). We may suggest another variant - the Greek "Monos" or "Mono", meaning "single", or "the only". Another option is to trace the name back to Mani, the founder of the Manichaean faith, a widespread religious current in the Middle Ages ([797], page 755). The name Osman is also very close to "Monos".

Brugsch translates the name "Senta" as "horrifying" ([99], page 117). We don't exclude the possibility that it might translate as "saint" (cf. the Latin "sanctus").

Brugsch believes that the name Khuni must be translated as "the cutter". We would like to know why it cannot stand for the Russian and Tartar word "Khan", or, alternatively "Hun" ("Hungarian") - or "Cossack", at that? See Orbini's book above ([161]).

There is nothing to preclude us from recognising the name of the "ancient" Egyptian god Bes ("the god of dancing, music and merrymaking", qv in [99], page 155), also known as "Bes the Jolly", as it turns out ([99], page 228), as the famous Slavic word "bes" ("demon").

The "ancient" Egyptian name Baba, which we find "re-emerging as the nickname borne by the father of our hero, Aames" ([99], page 263), can be identified as "papa", which means "father" in a great variety of languages.

We naturally don't insist that the "ancient" Egyptian name "Baba" ("papa") had always stood for "father" (male parent) in Egyptian texts. After all, the title "Pope" was also applied to the spiritual leader of the Christians. However, it is noteworthy that several examples of the name's usage cited by Brugsch feature it in the context of referring to a male parent - for instance, Baba the father of Queen Nubhas, Baba the father of Aames and "the king's right hand, Baba . . . says that he loved his father and respected his mother" ([99], page 263).

This is especially valid seeing as how "the full name of this father was Abana-Baba [or Abana the Father - Auth.], and he was the military commander of Ra-Sekhenen Taa III" ([99], page 263). Also, could the name of this king translate simply as "Russian Khan"?

In this case, the nation of Terter ([99], page 345) may be identified as the Russian Tartars, especially given that another inscription blatantly calls them "Tar-Tar" ([99], page 390).

The nation of "Kazaa (Gazi or Gatsi from the Adulis inscription)" ([99], page 345) could well be identified as the Cossacks.

The "Land of Punt" should therefore be "a coastal land", cf. the Greek "Pontos" ([99], pages 321 and 345).

The "Land of Athal" ([99], page 329) is either Italy or Ithil, the famous alias of the Volga.

The land of Sa-Bi-Ri ([99], page 390) might well be Siberia.

Sa-Ma-Nir-Ka ([99], page 391) is possibly Samarkand, or Sarmatia (Samara).

Ma-Ki-Sa ([99], page 390) might easily turn out to be Moscow.

Phurusha (or Thurusha, qv in [99], page 391) might be Thiras, or the Turks. Thiras was considered to be the forefather of the Turks in the Middle Ages, similarly to Meshech being the forefather of the Muscovites.

And so on, and so forth.

5. Egyptian kings of the Hiksos epoch.

This is what we learn from Brugsch: "The obscurity that surrounds the history of the invasion and the reign of the Hiksos kings in Egypt might be somewhat clarified by a single document that pertains to the end of the foreign rule" ([99], page 246).

An Egyptian papyrus kept in the British Museum today "contains the beginning of the historical tale of the foreign king Apepi [we have already mentioned him above - Apopi = the Christian Pope - Auth.] and the Egyptian vassal ruler Ra-Sekhenen (the name translates as 'Ra the Victorious Solar God')" ([99], page 247).

"Ra-Sekhenen wasn't the only king to bear this name. We know of three namesakes, his predecessors - all of them also shared the surname Taa" ([99], page 251).

Brugsch suggested to translate the name Ra-Sekhenen as "Ra the Victorious Solar God", qv above, adding that Amon-Ra was an Egyptian deity ([99], page 257) and that the name Khen, which is a part of the composite name Sekhenen, stood for "brave" ([99], page 251).

We shall refrain from arguing with Brugsch, since we haven't verified the decipherment method used for these hieroglyphs. But we must pay attention to the examples listed above. They demonstrate that in some cases (and, possibly, in many cases) Egyptologists appear to be incapable of giving a more or less reliable translation of names, which makes them wallow in guesswork and symbolic interpretation of the ancient hieroglyphs. But what holds us from suggesting our own version of interpreting the same "ancient" Egyptian names in this case?

Let us assume the following. Ra-Sekhenen is Ras-Kenen, or simply "Russian Khan". After all, the separation of the monolithic ancient text into individual words can also vary. Brugsch's translation of the word "Khan" as "brave" does not contradict our version, either.

Also, could the name Amon (MN unvocalised) be the first part of the word "monarch", which translates as "autocrat", or "the only ruler" (mono-rex), or the first part of the word "Mongol", or "the great"? This is precisely what we learn from the Egyptologists - Amon is "the great god".

It appears as though the "ancient" Egyptian name Baba as found upon the sepulchres of the Hiksos epoch can also be traced back to a Slavonic origin ([99], page 263). The most fascinating thing is the occurrence of the name "Bata" (or "Bita") in the "ancient" Egyptian papyri of the Hiksos epoch ([99], page 267). We recognise it as the name "Batu", or "batya" - the Cossack "batka", or Ataman, which must have also left a trace in Egyptian history.

6. The attitude to the Hiksos dynasty in Egypt. The epoch when the recollections of their reign started to get wiped out and the instigators of this process.

According to our reconstruction, after having invaded the African Egypt in the XIV century, colonised these uninhabited territories and founded a new dynasty, the Hiksos Cossacks, or the Mamelukes, who also impregnated the history and culture of Egypt with their Slavonic and Turkic names and customs, assimilated among the local populace; it was the French army of Napoleon that put an end to their long reign, or, rather, the reign of their descendants, qv above.

The names of the Hiksos Mamelukes, or Cossacks, became customary in Egypt. Egyptologists tell us the following: "The name Apopa, or Apopi [Pope - Auth.], which was borne by the Hiksos king, a contemporary of Rasekhenen [Russian Khan - Auth.] became common in Egypt . . . Egyptians voluntarily named their young after their so-called ancestral enemies [referred to as such by the Egyptologists - Auth.], without even hesitating to use the names of the foreign kings" ([99], page 259).

Brugsch calls this fact amazing ([99], page 259). Further he remarks that the Hiksos rulers and the locals "doubtlessly weren't hostile towards each other for generations, as legends [of Napoleon's epoch, perhaps? - Auth.] are trying to convince us" ([99], page 259).

Furthermore, according to Brugsch," the Hiksos rulers shouldn't be blamed for the destruction and desecration of temples, monuments built by other dynasties before them and so forth" ([99], page 259). On the contrary, Egypt is known for "a systematic destruction of the monuments built by the Hiksos, the defacement of their names and titles beyond legibility and the replacement of the latter by other names and titles in utter perversion of historical truth . . . They [the Egyptian kings of the 18th dynasty, regnant after the Hiksos, according to Brugsch - Auth.] managed to destroy all the vestiges left by the Hiksos upon the land of Egypt almost completely, and this is the reason why we run into so many difficulties in our study of the oldest foreign reign in Egypt" ([99], page 260).

We have already voiced our considerations in this respect. It is most likely that the "ancient" kings of the 18th dynasty had nothing to do with it. The mass destruction of inscriptions is to be blamed on the West Europeans; it must have started with the expedition of Napoleon. The traces of the Russo-Turkic dynasty of the Mamelukes were methodically erased. As Napoleon tirelessly proclaimed, Egypt "needed assistance on its way to the light" ([484], pages 80-82).