Part 5.

Ancient Egypt as part of the Great “Mongolian” Ataman Empire of the XIV-XVI century.

Chapter 19.

“Ancient” African Egypt as part of the Christian “Mongolian” Empire of the XIV-XVI century - its primary necropolis and chronicle repository.

8. Concrete in the "ancient" Roman Empire.

It has to be said that Scaligerian history did in fact preserve some information concerning the use of concrete in the "ancient times" - namely, the epoch of the "ancient" Roman Empire ([726]), which historians believe to postdate the construction of the Egyptian history by many centuries. Therefore, some of them remain calm about the possibility that the "ancient" imperial Roman constructions may have been built of concrete. It has to be said, though, that even in this case their references to the "Roman" concrete are rather cautious and restrained. It is easy to understand why - Scaligerian history is of the opinion that the "ancient Roman" concrete was forgotten in the dark Middle Ages to be "reborn" many centuries later. We must however state right away that the substance in question is most likely to be different from the geopolymeric concrete that we have described at length above - its manufacture involved a more simple procedure. Let us linger on this issue for a short while.

Historians tell us the following: "The imperial builders have developed a unique style of their own; concrete was the key to this new architecture. As early as in 1000 B. C. the Cretans, as well as the Greek settlers in the South of Italy (Great Greece), were using mortar made of sand, lime and water. But it was only in the II century B. C. that the Romans improved this solution, having created a recipe of concrete of their own, which was amazingly firm and almost fire-resistant. This concrete was made of water, gravel, lime and puzzolana - reddish-crimson fine sand of volcanic origin. This volcanic sand is an important part of hydrosylicate synthesis and allows the concrete mass to become denser . . .

Roman architects bravely began their experimentation with concrete. Massive foundations, wide arches supported by mighty concrete pillars, long arcades, sturdy concrete walls with brick and marble jacketing, domed roofs made of concrete - all of this was gradually changing the appearance of Rome. One of the largest constructions built of concrete was the Porticus Aemilia . . . In the beginning of the I century concrete was widely used for the construction of the gigantic Roman thermae - public steambaths, in other words [presumably - Auth.] . . . Basilica Iulia was the first basilica built of concrete. It was named after Julius Caesar, since its construction began during his reign" ([726], pages 25-26).

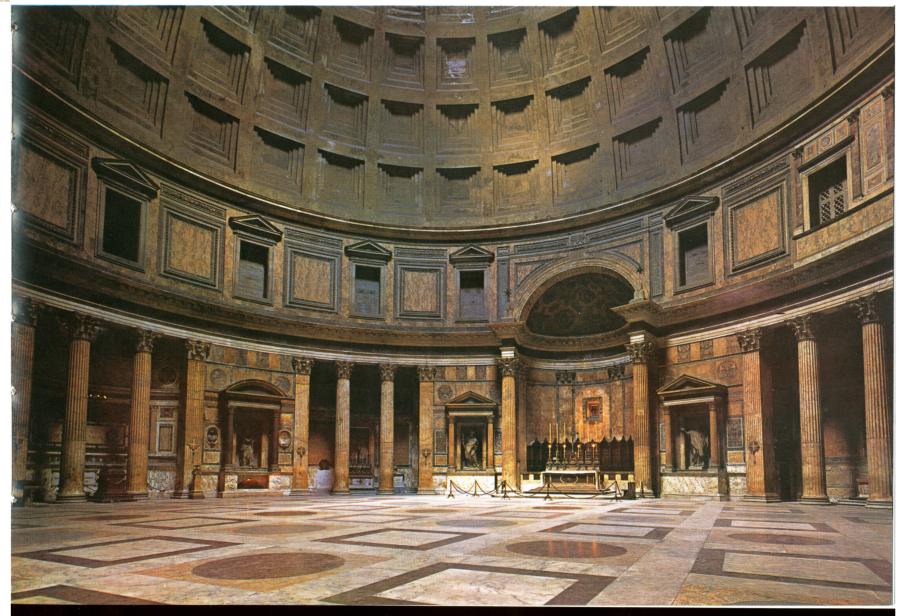

For instance, one of the most famous concrete buildings of the "antiquity" is the gigantic Pantheon in Rome, Italy. We learn that "the Pantheon was a temple built to honour all the gods by Hadrian [apparently, the Horde - Auth.] . . . it remains one of the greatest monuments built in the Ancient Rome . . . It was built between 118 and 128 A. D. [allegedly more than fifteen hundred years ago - Auth.] . . . There is an enormous facade with pillars . . . Every granite pillar equals 12.5 in height and 1.5 metres in diameter, weighing nearly 60 tons . . . the crown of the Pantheon's glory is its enormous dome . . . The inside of the dome is made of concrete, with 140 caissons . . . The mass of the dome diminishes as it curves towards the top - its weight was estimated as equalling 5000 tons. The thickness of the concrete layer equals 6 metres near the base, and a mere 1.5 metres near the round window. If the lower parts of the dome are made of concrete with brick and rock, the top section uses concrete with pumice stone, which makes it lighter . . . In 609 A. D. [allegedly - Auth.] Emperor Phocas gave the building to Pope Boniface IV, and the latter transformed the pagan temple into a church (Santa-Maria del Martyri)" ([726], pages 61-62).

In figs 19.82 and 19.83 we see the inside of the Roman Pantheon ([726], page 63; also [1242], page 41). The enormous and complex building is truly an architectural and engineering masterpiece. It is most likely that the Pantheon was built in the XVI-XVII century as the Christian church of Santa-Maria del Martyri. The use of concrete is perfectly natural - it was employed extensively in the architecture of that epoch.

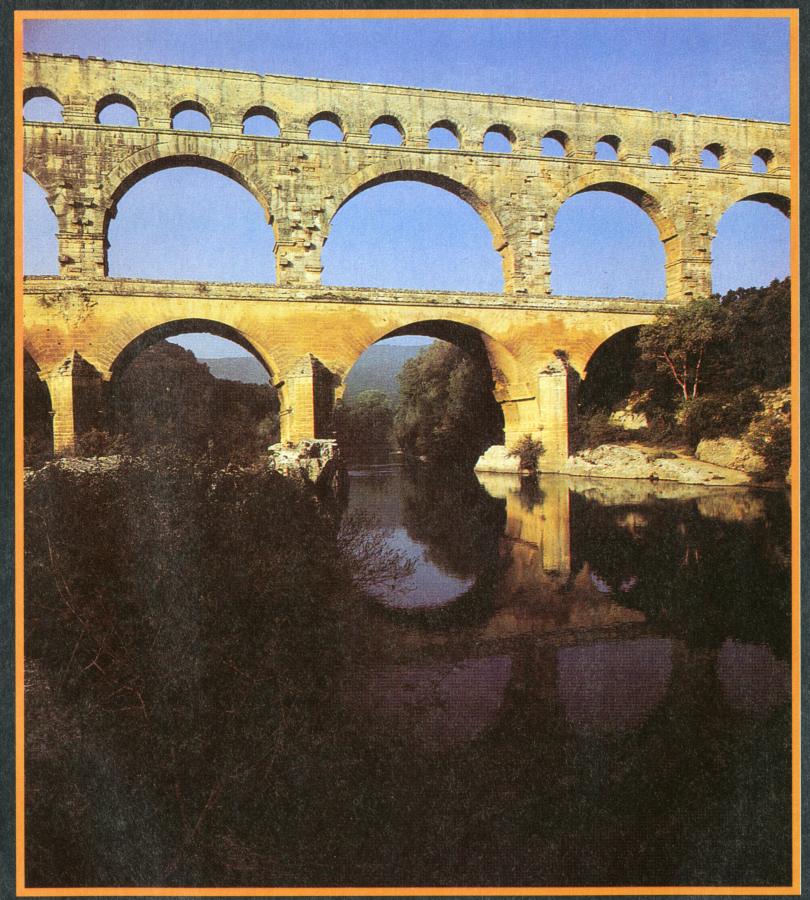

In fig. 19.84 we see another beautiful concrete construction that is also believed to be "ancient" - the famous "three-level aqueduct in Southern France that crosses River Gard . . . The construction, whose length equals 244 metres, supplied the city of Nemausus with 22 tons of water every day, which came from the distance of 48 km . . . The Pont du Gard remains one of the most brilliant works of the Roman engineering art" ([726], page 155). One cannot fail to notice the beautiful architecture and the meticulous planning of the engineers.

Another construction that comes to mind is the amazing "ancient" six-span bridge over the Tagus (nowadays known as Tajo) in Spain (fig. 19.85). It is still in use ([726], page 157). It is easy to see how accurately the granite and concrete blocks are fitted together; the architectural planning is impeccable.

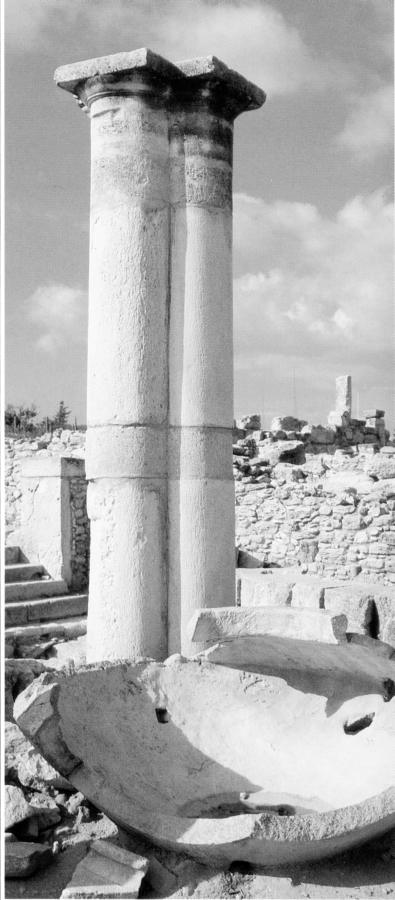

In fig. 19.86 we see the ruins of the Temple of Apollo Ilatis in Cyprus. The temple was erected in the alleged II century A. D. ([384], page 29). In the foreground we see the ruins of the temple's dome and a part of a construction that looked like a spherical sector. One sees that the thickness of the construction is absolutely even. The "ancient" construction was obviously cast of concrete in a mould, hence the even thickness. It is obvious that the "ancient" construction was cast of concrete, in a specially prepared mould - nobody would spend years carving it out of stone!

Yet historians are trying to convince us that these and many other beautiful and enormous concrete construction of the "antiquity" were erected during the first few centuries of the new era - more than fifteen hundred years ago, that is, in the epoch when the "arabic" numerals, logarithms, the conception of zero and so on had not been invented yet, according to the very same Scaligerian history. We are being told without any proof whatsoever that the "ancient" engineers and builders were conducting extremely complicated technical and architectural calculations using the cumbersome Roman numerals. Try multiplying or dividing two numbers with the use of Roman numerals, or doing a square or cubical equation in their terms, or a system of linear equations. At best, you shall waste a great amount of time, and only manage to solve the simplest ones.

It is perfectly clear that in order to develop a sound strength of materials theory or a complex estimation of loads, as in case of the Pantheon or the arches of the aqueducts, one absolutely needed evolved mathematical methods, which only appeared in the XV-XVII century. The construction of large-scale buildings, sturdy and elegant, in any prior epoch is right out of the question - yet we are being told that they all date from the time when Europeans couldn't even invent stirrups. Let us remind the reader that the very same Scaligerian chronology claims stirrups to have been invented several centuries after the epoch of the "ancient" Hadrian ([116:1], page 26). Could the construction of the luxurious Pantheon with all of its outstanding engineering solutions have been easier for the "ancients" than the invention of stirrups?

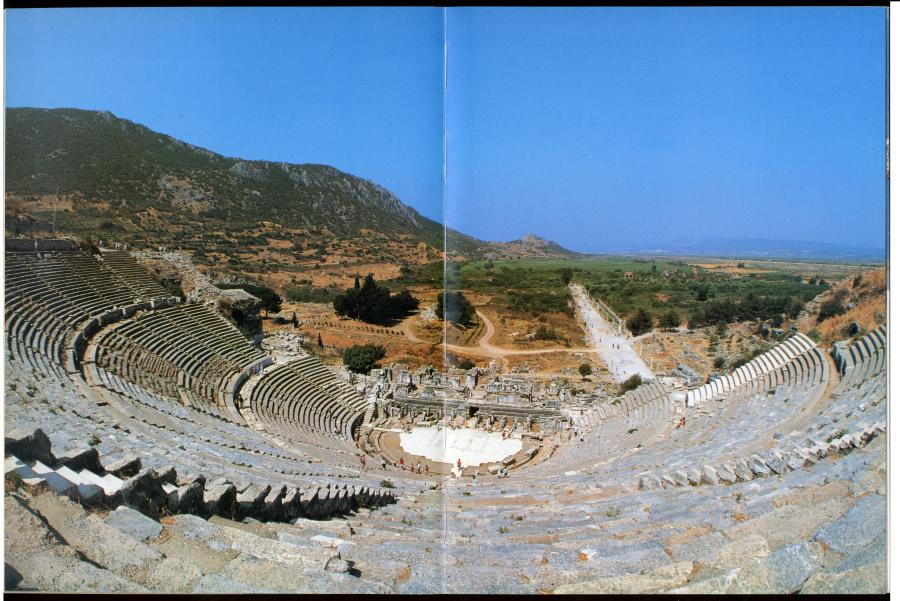

According to the report of A. V. Nerlinskiy, who visited the "ancient" amphitheatre in Phaselis, near Antalya, on the Mediterranean coast of Turkey, the blocks that the amphitheatre was built of also make the impression of being made of concrete. They are getting eroded now, and one sees inclusions of harder pebbles, whose size is more or less uniform, which is usually the case with concrete. The steps of the "ancient" amphitheatre in Ephesus make a similar impression - this is even visible on the photographs published in [1259], for instance (pages 88-89). See figs. 19.87 and 19.88.

As we are beginning to realize, the "ancient" Rome is a reflection of the mediaeval Great = "Mongolian" Empire of the XIV-XVI century, and so the use of concrete in this epoch is perfectly normal.

Above we mention stirrups. Scaligerian history assumes them to have been invented in the IV-VI century A. D. in Korea, Japan or China ([116:1], page 26). However, this information is believed to be rather nebulous. S. Vainshtein and M. Kryukov, Doctors of History, admit that "in the IV-VI century artwork that depicts saddled horses, stirrups look rather unclear" ([116:1], page 26). According to Scaligerian chronology, stirrups came to Europe even later than that. We are therefore being told that the "ancient" Roman, "ancient" Persian, "ancient" Scythian and "ancient" Assyrian cavalry didn't have any stirrups! Try aiming from a bow sitting on a horse without stirrups. You won't succeed.

It is most likely that the stirrups were invented shortly after humans tamed horses and started to use them for transportation. The "no-stirrup" period must have been very brief. Historians are perfectly justified to point out that "the invention of the stirrup was a major event in the history of material culture . . . It was owing to the stirrups that a new cavalry could appear, armed with sabres, heavy armour-piercing spears and long-range bows . . . The invention of the stirrups greatly affected many forms of military organization, having introduced new colours into the social history of Europe and Asia, in a way. One cannot imagine a mediaeval knight in heavy armour sitting on a horse without any stirrups" ([116:1], page 24).

According to our reconstruction, as soon as the stirrups were invented in the Middle Ages, cavalry instantly became a mighty strike force, which was immediately used by the rulers to their advantage. It is possible that the stirrups became widely used in the very epoch of the Great = "Mongolian" Conquest, when the Cossack cavalry played a decisive part in the formation of the Empire in the XIV century.

The situation with saddles is similar as per the Scaligerian version of history. It is assumed that the really comfortable saddle only appeared in the VII-VIII century. Historians write that "it became much easier to mount a horse, to turn around while riding, and to bend over, forwards or backwards, which was particularly important for the use of the new weapon - the sabre. The invention appears to have been made by the ancient Turkic tribes of nomads, who passed it on to the later Shanbi tribes, the Chinese and other nations in Central and Eastern Asia. In the VII-VIII century, as the ancient Turkic culture became more influential and widespread, the new type of the saddle became used far beyond the Turkic world by many Asian and European peoples" ([116:1], page 26). Everything is perfectly clear. The events in question date from the XIV-XV century, when the Great = "Mongolian" Conquest engulfed the vast territories of Eurasia and America, and not the VII-VIII century.

9. The Mamelukes and the monuments of the "ancient" Egypt.

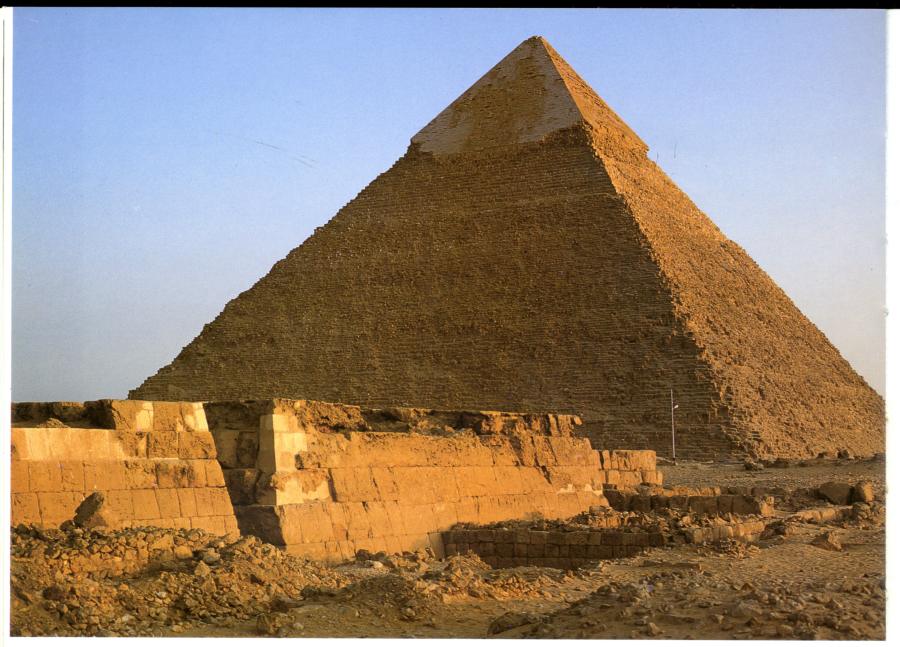

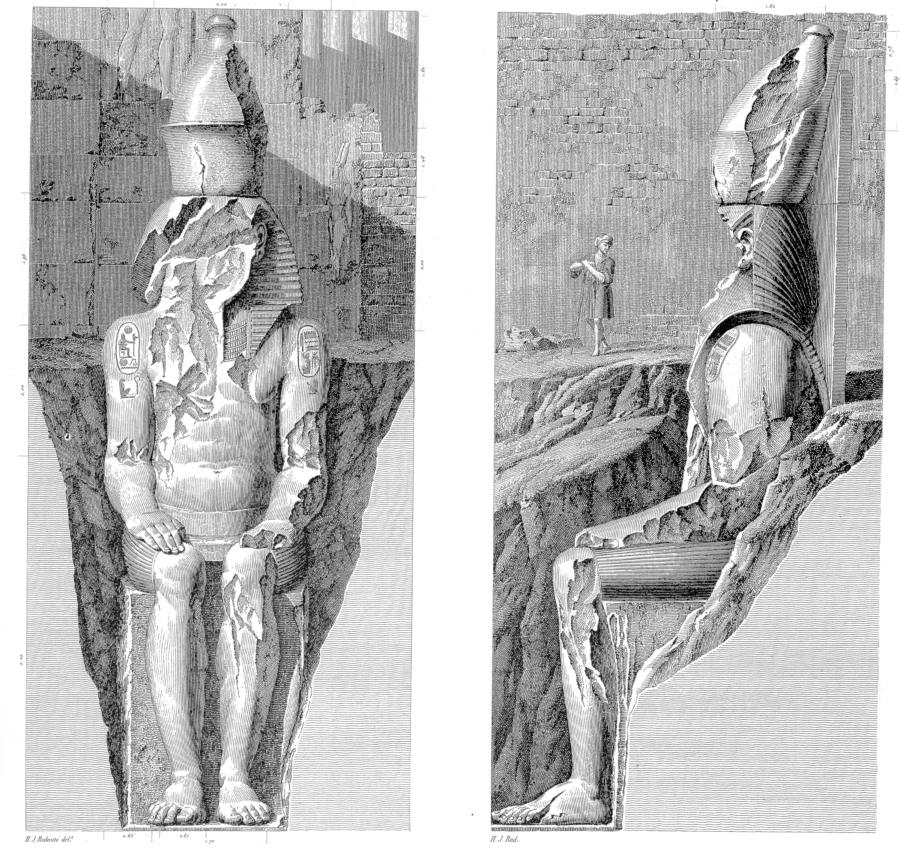

Let us finally consider the European monuments once again. In fig. 19.89 we see the Pyramid of Khephren - the second largest pyramid in the Giza (Cossack) Field in Egypt. The drawing was made by the artists who came to Egypt with the invading Napoleonic army ([1100], A. Vol. 5, Pl. 10). The modern condition of the Khephren Pyramid can be seen in fig. 19.90.

In fig. 19.91 we see a rare photograph of 1864, where it is plainly visible that the Great Sphinx and its environs were in a truly lamentable state during that time ([1415], page 44). In the background we see the Khephren Pyramid. The Sphinx is almost entirely covered by sand. Let us remind the readers that Napoleon's soldiers shelled it from cannons at point-blank range ([380], page 77; see above). Such attitude towards the Egyptian monuments from the part of the Western Europeans is easy to understands. Under Napoleon, the armies of the Western Europe, which broke apart from the Great = "Mongolian" Empire in the XVII century, during the Reformation mutiny, finally managed to invade one of the most important regions of the former Empire. It is possible that apart from military considerations Napoleon was also driven by a feeling of revenge. Having thrown off all reserve, Western Europe was wreaking havoc and destruction upon the former imperial graveyard, avenging their former subordinate state on the mummies of the Great Czars, or Khans, and the monuments of the Horde and the Atamans dating from the XIV-XVI century. The enormous monuments were falling to pieces shattered by cannonballs (fig. 19.92).

Similarly, many Egyptian statues and temples were defaced earlier, in the XVI century, by the invading Ottomans (Atamans), and then by the iconoclastic Muslims. These ruined Egyptian constructions must have been buried particularly deep under layers of sand when they were discovered by the Europeans. Nevertheless, the fact that the Great Sphinx was shelled from cannons by the Napoleonic soldiers ([380], page 77), speaks volumes of the fact that the West Europeans, who came to Egypt with Napoleon, did actually destroy the Egyptian monuments.

It has to be borne in mind that "Egypt was never afflicted by earthquakes" ([2], page 71). Therefore, the granite statues and the obelisks of Egypt weren't destroyed by subterranean forces, but rather cannonballs and kegs of gunpowder.

The idea to ascribe all the destructions to the Egyptians must have occurred to the Europeans subsequently. This delegation of blame was implemented actively, albeit surreptitiously. The necessity of such delegation is unlikely to have been voiced all that actively. However, the results of yet another sly revision of history are visible perfectly well. Modern book on Egyptian history, published in Europe between 1990 and 1998, for instance, are already silent about the cannons of Napoleon and the shelling of the Egyptian monuments for some reason. However, it is being said that the Great Sphinx was shelled by the Mamelukes. Let us quote from the book of Abbas Shalabi ([2]) as an example, published in Italy in 1996 under the editorship of Giovanna Maggi, an Italian author. Shalabi obediently writes the following: "As for the marks of destruction on the face of the legendary man-beast, they partially result from erosion, and partially from the cannons of the Mamelukes, who had used it for exercises in aimed gunfire" ([2], page 38).

Or let us consider another book on the history of Egypt, also published in the Western Europe - in Italy, to be more precise, written by Alberto Carlo Carpicecci ([370]). Nary a word about the cannons of Napoleon. Instead, we see the following version introduced very persistently: "The Sphinx was defaced by the people rather than the passage of time: indeed, its head, floating over the sands, was used by the Mamelukes as a target for their artillery" ([370], page 66).

Books, albums and guidebooks with such tendentious "magisterial explanations" have virtually flooded the entire tourism industry of Egypt. You can buy they everywhere - in shops, museums, next to the pyramids and numerous monuments. Many thousands of such books are sold. Following the "authoritative authors", numerous Egyptian guides also explain it to the gullible tourists what barbarians their own ancestors, the "vile" Egyptian Mamelukes, really were. Just to think that they destroyed the Egyptian halidoms instead of protecting them - with gunfire, no less.

However, the modern propaganda-mongers often lack consistency. Elsewhere, the author of the same Italian book is careless enough to remark that the Mamelukes were good and prolific builders. As we find out, "the epoch of the Mamelukes (between 1250 and 1517 A. D.) becomes an important period for the urbanization of Cairo, which continued under the Ottomans, who were also encouraging trade" ([370], page 45). In another guidebook we read that "the Mameluke epoch (1250-1517 A. D.) became a time of urban construction and flourishing trade for Cairo" ([2], page 22).

Therefore, the Mameluke Cossacks were by no means a wild tribe that plagued Egypt - on the contrary, they were conscientious owners and capable rulers.

Apparently, the Mamelukes formed a secluded military caste in Egypt, just like the Samurai in Japan, barely mixing with the rest of the populace at all. According to our reconstruction, they were the Cossack rulers of Egypt hailing from the Horde. They guarded the central imperial graveyard, overseeing the construction of the funereal complexes. The Mameluke estate was destroyed in the XIX century, after Napoleon. Europeans became the subsequent rulers of Egypt and started to convince the local population that their former Mameluke rulers were vicious and evil - didn't they shell the Sphinx and deface all the monuments of the "ancient" Egypt, after all? And so on, and so forth.

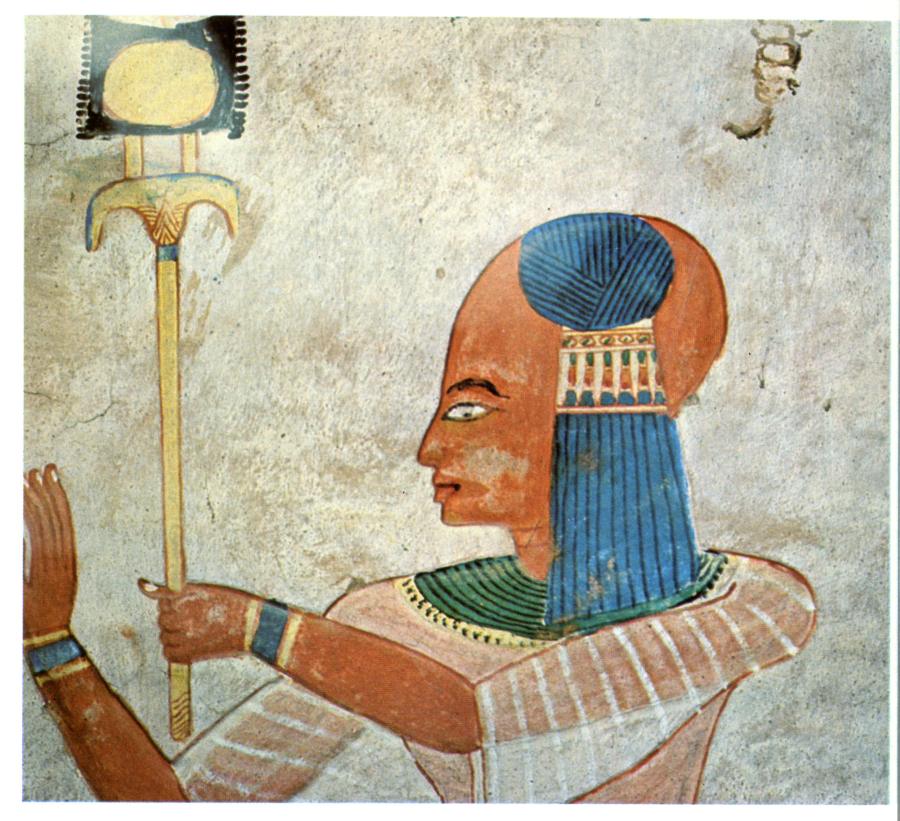

Let us pay attention to the Cossack "oseledets" hairdo depicted on an "ancient" Egyptian fresco (see fig. 19.93). It is a long lock of hair left on the top of an otherwise cleanly shaven head; this hairdo was typical for the Cossacks of Zaporozhye. A similar "oseledets" can be seen on the head of the "mind-bogglingly ancient" Egyptian Prince Khamuasta, one of the children of Ramses III. He lived in the alleged second millennium before Christ ([270], page 118). As we realise today, this is disinformation - the character in question lived in the epoch of the XIV-XVI century A. D. Commentators have a good reason to voice their amazement at the excellent condition of the "ancient" artwork: "The colours . . . are still so fresh, as though the frescoes was painted yesterday" ([370], page 121).

By now, a significant part of the "ancient" Egyptian artwork has been deliberately mutilated; first and foremost - the inscriptions, as well as the faces of the figures. The faces of many stone effigies were chiselled off, just like the faces of the Russian "stone maids of the Polovtsy" (see CHRON5, Chapter 3:6). In fig. 19.94 we see an "ancient" Egyptian fresco. Its condition in general is good enough - however, not a single face has survived on it. We are being told that the iconoclastic Muslims should be blamed for that. But what about the faces of the "stone maids of the Polovtsy" in Russia? The manner is exactly the same; yet there was no iconoclasm in Russia during that epoch. It is most likely that the Egyptian artwork was mutilated by the West Europeans in the epoch of the XIX century, already after the advent of Napoleon. A possible reason is that the facial types were too European, or Slavic. The presence of numerous Slavic faces in the "ancient" Egyptian artwork may have led to unnecessary questions and doubts. The faces of the "stone maids" were chiselled off for the same reason - the culprits were the vehement devotees of Scaligerian and Millerian history.

By the way, we have to enquire whether all of the objects discovered by the archaeologists in the "ancient" Egyptian tombs can be seen in books and museums. Are all the findings shown to us today?

10. Egyptian pyramids as the Scythian burial mounds.

It is usually assumed that the Egyptian pyramids are something unique and inimitable. At least, it is presumed that there are no pyramids in either Europe or Asia, nor have there ever been any. This is not so in reality. Pyramids are known quite well in Eurasia - in Russia in particular. If we are to compare a pyramid to a burial mound, we shall easily recognize the two as the same construction. It is also obvious that the burial mounds preceded the pyramids, and not the other way round. The great Egyptian pyramids are, in a way, the highest point of "burial mound engineering", where the old art of making burial mounds reached perfection.

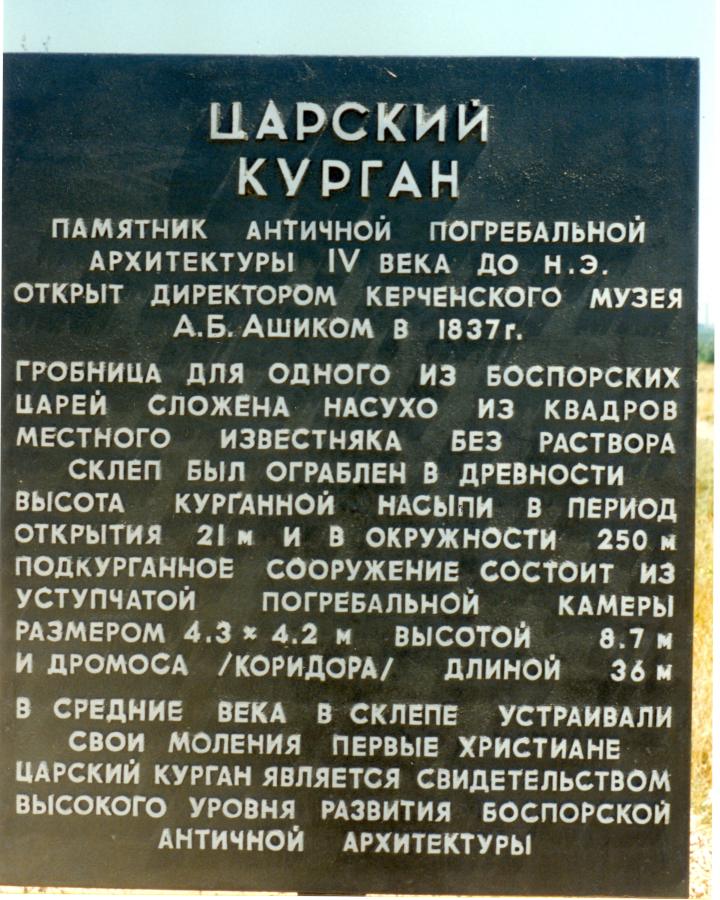

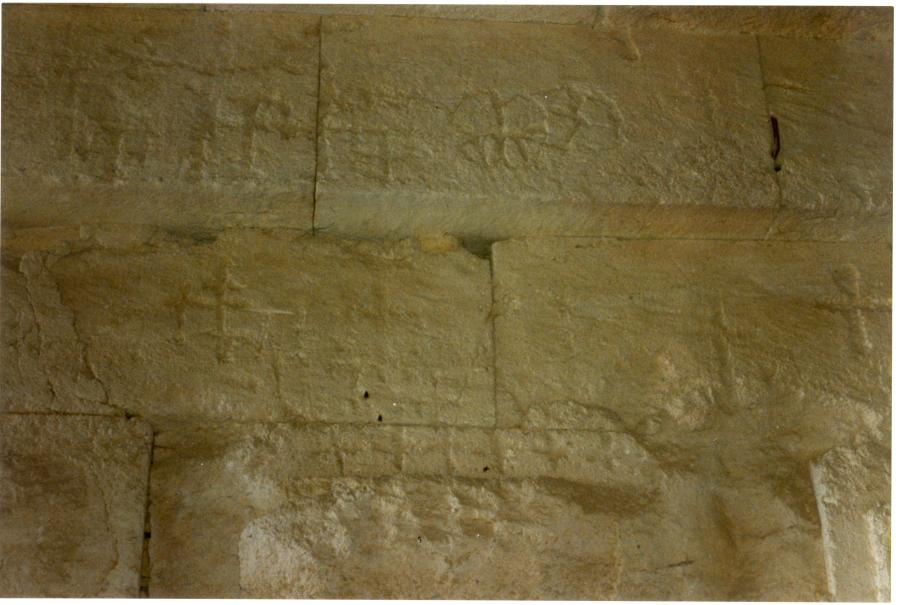

Let us explain. What is a burial mound, exactly? Mounds weren't necessarily used for burials - they were also used as public buildings such as churches. For example, the gigantic "Mound of the Kings" near the city of Kerch in the Crimea was a Christian church in in the Middle Ages. It is a known fact, reported in the explanatory plaque next to the entrance to the mound (see figs. 19.95, 19.96, 19.97). Inside the mound, on its stone walls, we see remains of Christian crosses (figs. 19.98 and 19.99).

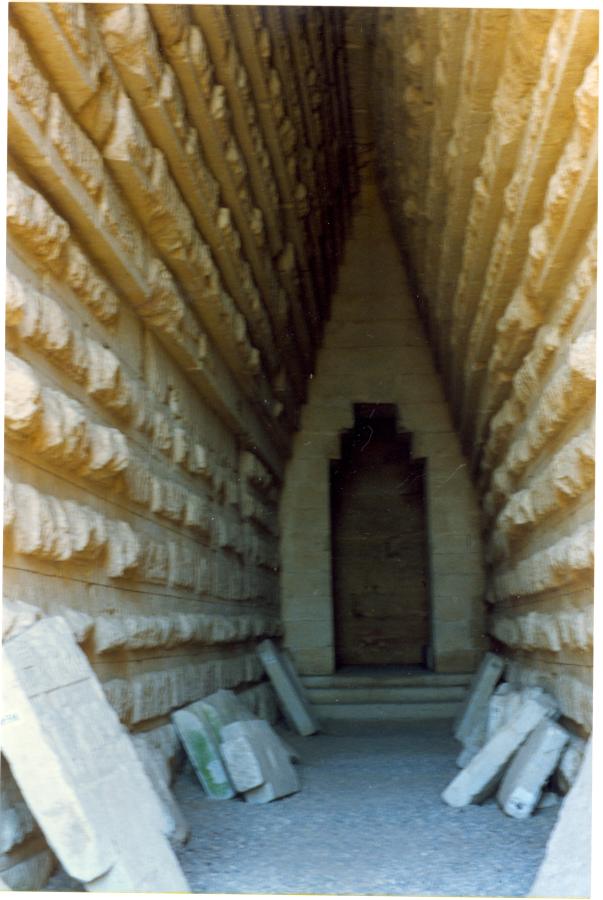

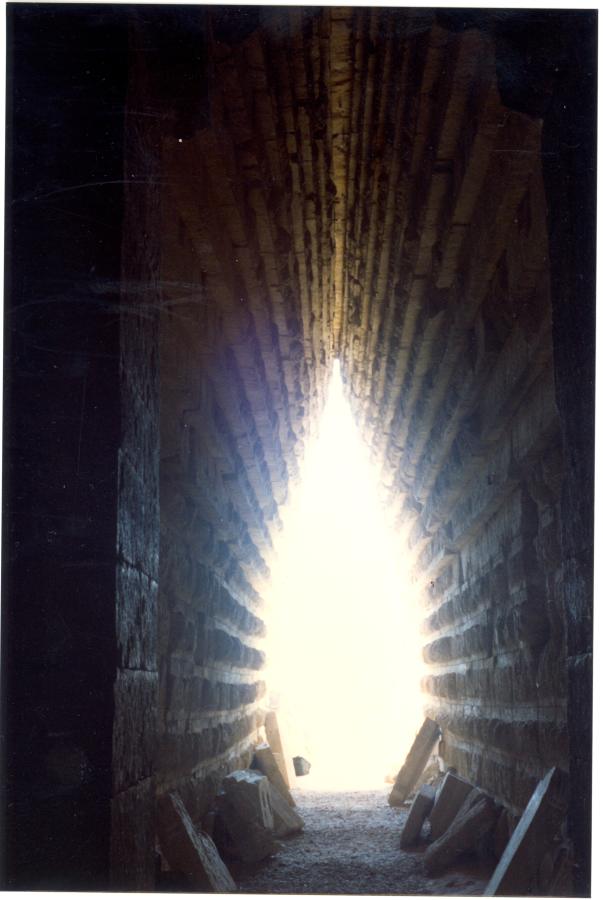

However, historians are trying to convince us that the mound was a sepulchre initially (see fig. 19.97). However, the sepulchre was robbed in times immemorial; the remains of the tombs were removed, and after that it was used as a church exclusively. However, how is one to explain the fact that the inside of the mound is built like a Christian church? It has an altar-room with excellent acoustics, imperial gates and a room for the praying. There are three steps leading to the pulpit, as it is customary for Christian churches (fig. 19.100). In fig. 19.101 we see a photograph of the mound's altar taken from the imperial gates. In fig. 19.102 we see the interior of the church between the pulpit and the exit from the church. In fig. 19.103 we see the entrance to the mediaeval Russian mound, or church.

We have to point out that the inside of the mound had looked like a church from the very beginning. It could not be rebuilt without the destruction of the entire mound. The implication is that we see an authentic mediaeval Christian church and not a burial mound converted into one. Similar mounds of a much smaller size, with no pulpit or imperial gates, must have been used as houses, or residential buildings. After all, a church is still a house - with certain details that make it different from a residential building, but a house nonetheless. Therefore, pyramids and mounds are ancient houses, which were built before the invention of mortar (such as cement). A mound or a pyramid are perfectly natural constructions of stone, built without mortar. Such mounds were covered with earth to keep the rain outside. The primary difference between the mounds and the Egyptian pyramids is that the latter aren't covered with earth. However, this is explained by certain traits of the Egyptian climate. Earth is extraneous, since there is no rainfall here.

Mounds were built in Russia up until the XX century. They weren't used as residential buildings, but rather as storage facilities. In Russian villages they were called "exits" or "babylons", no less. According to Dahl's dictionary, "exits, or babylons in the Astrakhan region, were storage facilities of a complex construction" ([223], Volume 1, column 796). These "exits", or "babylons", can still be seen in many Russian villages (fig. 19.104). Their size is usually small; they are built of wood and stone and covered with earth. The construction is that of a typical mound; the interior is similar to that of the "Mound of the Kings" as discussed above, with a long corridor ending with the entrance to a large square chamber.

In Russian villages these "exits", or "babylons" are made of wood more often than stone, since wood is more common in Russia than stone. Further to the south, stone was used more often. We see that the name "babylon" was used in the Russian language for referring to the construction of the old kind, which appeared long before mortar. Such archaic pyramids were built in Egypt as well. At the same time, the gigantic Egyptian pyramids were built at the highest level of building technology. Their XIV-XVI century creators, invaders from the Horde, must have reproduced the archaic shape common for Russia, or the Horde. This is understandable enough, since Egypt was the imperial graveyard of the Great = "Mongolian" Empire. It is perfectly natural that the archaic "ancestral" shape was reproduced in their construction, albeit with the use of the most innovative building technologies of the epoch, such as concrete.

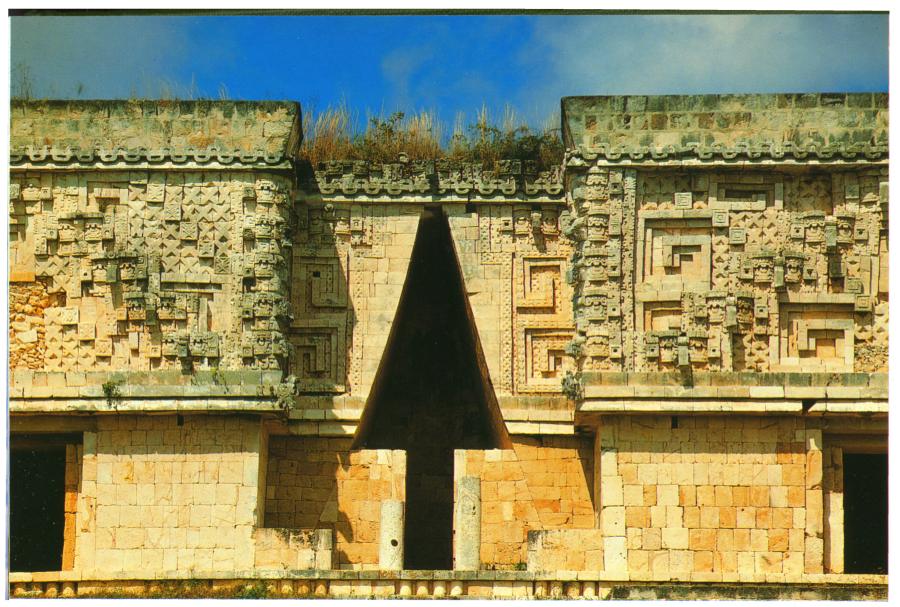

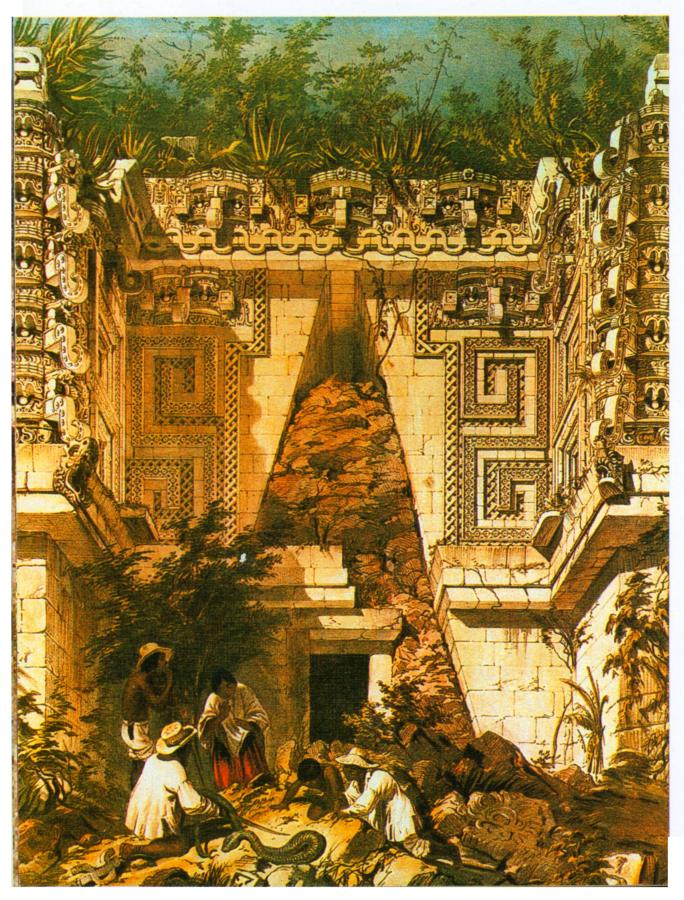

Mounds, or pyramids, weren't only built in Eurasia and Africa, but also in America - in the XV century the earliest, which is where the wave of the Horde and Ottoman conquest reached that continent. The architecture of the "ancient" Mexican pyramids and palaces is also clearly traceable to the European mounds, or pyramids, as built in Russia (or the Horde). For instance, the characteristic entrance, which looks like a tent, or an isosceles triangle (see above, in fig. 19.103). In fig. 19.105 we reproduce the photograph of the entrance to the ancient stone royal palace in Yucatan, Central America. We see the same characteristic triangular shape as in the Russian "Mound of the Kings". The narrowing of the entrance as seen below is a later addition, which can be seen by the seam in the masonry. Apart from that, there is an older picture of the same entrance dating from the XIX century, where there are still no walls that make the lower part of the entrance narrower, qv in fig. 19.106. We see the entrance to be triangular, getting narrower towards the top.

Some of the modern commentators point it out themselves that the "ancient" Egyptian Pyramid of Khephren, for instance, was planned as a gigantic mound, or a hill over the burial chamber ([370], page 59).