Part 5.

Ancient Egypt as part of the Great “Mongolian” Ataman Empire of the XIV-XVI century.

Chapter 20.

Pharaoh Thutmos III the Conqueror as the Ottoman = Ataman Mehmet II, a conqueror from the XV century.

6. The Egyptian obelisk, the Serpent Column, the Gothic Column, and the knightly statue of Emperor Justinian in Istanbul. The name of Moscow.

Let us return to the Egyptian obelisk of Thutmos III, which we mentioned above. It can be seen in Istanbul to this very day – right next to the Hagia Sophia, on the square where the famous Hippodrome used to stand (see figs 20.3 and 20.7). It is one of the most important sights in modern Istanbul. It is curious that the gigantic obelisk of pink granite “was installed on a marble pedestal with statues that reflected the life and the heroic deeds of Theodosius” ([240], pages 163-164). According to Jalal Assad, the height of the column equals 30 metres, and the width of the obelisk at the bottom equals two metres ([240], pages 163-164). The pedestal of the Obelisk of Thutmos (or Theodosius) can be seen in figs. 20.8 and 20.9.

Let us remind the reader that Theodosius I was the famous Romean emperor of the alleged IV century A. D. On the pedestal of the obelisk we see the following phrase in Greek and in Latin: “Theodosius I, with the aid of the praetorian prefect Proclus, installed this rectangular column, which had lain on the ground, upright” ([240], page 164).

Scaligerite historians are obviously going out of their way in order to “explain” the combination of two great names upon a single monument – the former belonging to the Egyptian Thutmos III, and the latter, to the Romean Theodosius I. The two rulers are believed to be separated by millennia. Historians offer us the version about this obelisk being “erected by the Egyptian King Thutmos III in Deir el Bakhri in the XV century B. C. Some 2.000 years later, Emperor Theodosius I took the monolith away to Istanbul – in 390 A. D.” ([1464], page 48).

Suddenly we find out that there is no accordance among historians even insofar as the identity of the person who brought the obelisk to Constantinople is concerned. According to Dethier, the column was erected in 400, during the reign of Arcadius” ([240]), page 164). The northern bas-relief on the monument’s base is presumed to represent “Arcadius and his wife Eudoxia chanting a Kathisma” ([240], page 165). However, according to the very same Scaligerian history, Arcadius reigned after Theodosius I!

What do we get as a result? First Theodosius I installs a monument with his own effigy. Arcadius, his successor, gives orders for his own image to be carved on the monument. Destroying some of the inscriptions dating from the epoch of Theodosius, perhaps? All of this looks very strange, and may be nothing but a quirk of the Scaligerian chronology.

A meticulous study of the pedestal whereupon the Thutmos Obelisk is installed immediately tells us that the lettering on the memorial was altered without a doubt – we claim blatant forgery to be the case in one instance at least (the name Proclus, which obviously came to replace some other name, one that had been chiselled off. A photograph of the lettering on the base of the obelisk can be seen in fig. 20.10. The forgery is an obvious fact (see fig. 20.11). Some word was chiselled off, which has resulted in the formation of a rectangular groove that is deeper than the rest of the lettering. A new name (PROCLO) is obviously a replacement, followed by the letter S (the ending of the obliterated name). The knights of hammer and chisel were very laborious in their endeavours to make history correspond to their fancies.

Furthermore, the inscription on the pedestal is telling us that before it was installed upon its pedestal, the obelisk was laying on the ground, and that it was set upright – nary a word about its transportation from faraway Egypt! The inscription is perfectly easy to understand in this case – first, the obelisk was transported from the quarry, then the inscriptions were made. The next obvious thing to do is to install the obelisk in an upright position. This was promptly done. “The sculptures in the lower part of the pedestal reflect the preliminary works required for the obelisk to be installed upright” ([240], page 165). Or, alternatively, it could have been cast of concrete right on the spot, the “elevation theory” being of an apocryphal character.

Our opinion is that this outstanding monument was indeed made in the XV-XVI century, in the epoch of the Ottoman = Ataman Empire, in the exact form and shape we see today. However, the text upon the obelisk was in hieroglyphs, which corresponded to a ceremonial language used by the clergy for solemn occasions. Latin and Greek inscriptions were directed at the majority of the Empire’s population. Another option is that the Greek and Latin lettering was added at a latter point, which is all the more likely that some of the fragments were definitely altered by diligent Scaligerites at some point.

Next to the Obelisk of Thutmos (or Theodosius) we see another important monument – the Serpent Column. This column is made of bronze and believed to be “Istanbul’s oldest Greek monument” ([1464], page 48). It was erected in the alleged year 479 B. C. by the Greek poleis that crushed the Persians in the Battle of Plataea, which is when the Greeks put Xerxes to complete rout.

The monument is a column woven out of three thick serpent bodies (see fig. 20.12). Nowadays the column’s height equals some five metres, its top part is missing. The golden sphere that used to crown the Serpent Column has also disappeared ([1464], page 48).

“These snakes also used to support the famous golden tripod, which was sacrificed to the Delphic temple of Apollo . . . This column used to be eight metres high, but its height doesn’t exceed five metres these days. The golden vase that was once supported by the three serpent heads was three metres in diameter” ([240], page 166).

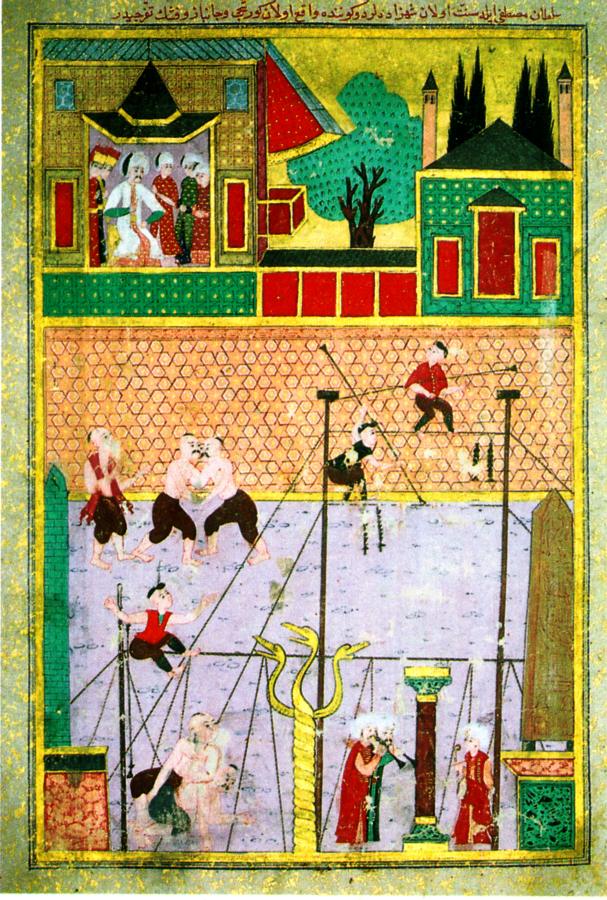

In fig. 20.13 we reproduce an ancient miniature that depicts a feast in Istanbul, which is observed by Suleiman the Magnificent from the balcony of his palace. The Serpent Column can be seen below; it has the shape of three interwoven serpent bodies (fig. 20.14). On the left and on the right we see the obelisks of Thutmos (Theodosius) and Constantine, which still stand on the Hippodrome of Istanbul.

One is instantly reminded of the famous Biblical legend of the Fiery Serpent

“And the LORD said unto Moses, Make thee a fiery serpent, and set it upon a pole . . . And Moses made a serpent of brass, and put it upon a pole, and it came to pass, that if a serpent had bitten any man, when he beheld the serpent of brass, he lived” (Numbers 21:8-9). What the Biblical “fiery serpent” really was shall be explained in Chapter 4:10 of CHRON6 – it is no column, but rather a large cannon. However, later readers of the Bible could have forgotten the truth and believed that Moses really made a copper column. It is possible that this literary theory could be made material as the bronze column that looks as interwoven serpent bodies – in the Hippodrome of Istanbul, right next to the Hagia Sophia.

The ancient miniature in fig. 20.13 tells us quite a few more interesting facts. For instance, it is plainly visible that the foundations of both obelilsks, the Egyptian (right) and the Column of Constantine (left) are decorated with pink marble and green malachite. There aren’t any inscriptions or bas-reliefs on the pedestals. Therefore, they must have been installed here in the second part of the XVI century, and not any earlier – yet we are told about their alleged “mind-boggling antiquity”.

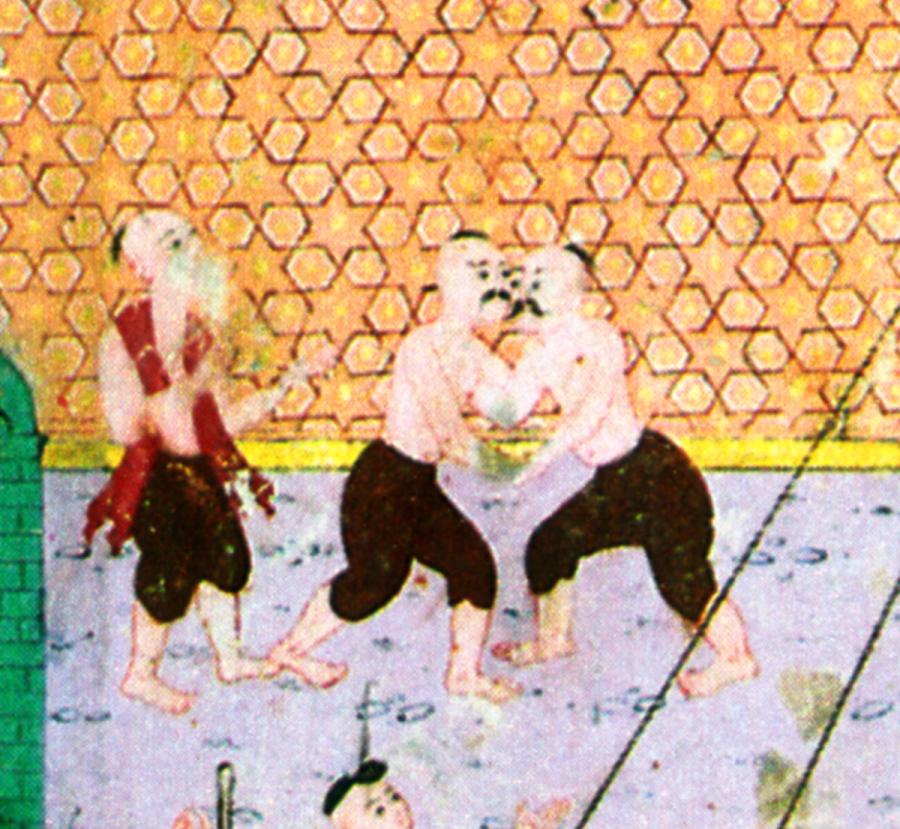

Furthermore, what we see at the centre of the miniature is two wrestling warriors – typical Russian Cossacks with moustaches and oseledtsi hairdos (see fig. 20.15).

Another interesting monument one finds in Istanbul is the famous Column of the Goths. “There is a Corinthian column in the garden of the Emperor’s palace – fifteen metres tall, carved out of a single piece of granite. The lettering is as follows: “Fortunae reduci ob devictos Gothos”. This column, which used to support the statue of Byzantes, according to Nicephoras Gregoras, is one of the oldest Byzantine monuments” ([240], page 170). Indeed, as we have already figured, the Goths played an important part in the history of Constantinople.

Another amazing construction used to stand at the Hippodrome of Constantinople – one that hasn’t survived until the present day. It is an equine statue of Justinian I, Emperor of Romea regnant in the alleged VI century. According to Jalal Assad, “it was facing West . . . The seraglio library has preserved a drawing of this statue dating from 1340; it corresponds to the descriptions of Byzantine authors well enough. The Emperor is portrayed as a knight, with an enormous feather on his helmet, which looks like the tail of a peacock” ([240], page 170). Our reconstruction makes this blatantly mediaeval portrayal of the allegedly “ancient” Romean emperor perfectly understandable.

Another remark is as follows. Any small mosque is called a “mescit” in Turkish. This might be related to the Russian word “skit” in some way, which translates as “skete” (small monastery). The existence of such a link is perfectly plausible, given that the Horde and the Ottomans formed a single empire for many centuries. Also, one might dwell on the homonymy of the English words “mosque” and “Moscow” (and also “Mecca”).

7. Some parallels between the biographies of Alexander the Great and Sultan Suleiman I the Magnificent.

Above we have made many references to the “ancient” Egyptian pharaoh Thutmos III, a double of Sultan (Ataman) Mehmet II, who lived in the XV century. Simultaneously, according to the mathematical and statistical result as related in CHRON2, Chapter 3:18, Mehmet II also became reflected in history as the “ancient” Philip II the Conqueror – the father of Alexander the Great. One should therefore expect to see another famous sultan as a successor of Mehmet II – the person whose biography served as yet another source of legends about Alexander the Great.

The most interesting thing is that our expectations are met – there is but one candidate for this role, the famous Sultan Suleiman I the Magnificent (the Conqueror), who lived in 1495-1566 and reigned between 1520 and 1566 ([797], page 1281). He was known as Suleiman Canuni in Turkey (ibid). The name “Canuni” may be a slight modification of the word “Khan”, which is well familiar to us. This leader is supposed to have “taken the Ottoman Empire to the very summit of its political might” ([797], page 1281). Suleiman I was also known as “Lawgiver” ([240], page 322).

We didn’t analyse the biography of Suleiman I in that much detail – however, we have to point out several vivid parallels that one notices instantly. First of all, Alexander the Great is believed to be the son of the “ancient” king Philip II the Conqueror (797], page 1406). His partial prototype, Suleiman I, was the great-grandson of Mehmet II the Conqueror ([1404], page 561), a possible prototype of the “ancient” Philip II the Conqueror. However, Suleiman’s epoch isn’t too far away from that of Mehmet II – the latter died in 1481, whereas Suleiman I was born a mere 13 years later, in 1494.

Thus, both versions, the “ancient” and the mediaeval, report a close blood kinship between the two greatest conquerors: father ----> son or great-grandfather ----> great-grandson.

Furthermore, the wives of the “ancient” Alexander of Macedon and the mediaeval Suleiman I the Magnificent were all but namesakes – the wife of Alexander was called Roxana ([1370], page 219), and the wife of Suleiman I bore the name Roxelana ([1464], page 61).

Incidentally, mediaeval sources report that Roxelana was Russian ([1464], page 61). In general, during the epoch of the Ataman Empire, “the beauty . . . of the Russian, Georgian and Cherkassian girls made them the first candidates to be taken to the palace [of the Sultan – Auth.]” ([1465], page 79).

Michalo Lituanus, a mediaeval author, calls Roxelana “the favourite wife of the regnant Turkish Emperor” ([487], page 72), while the commentator reports that “Roxelana . . . the Ukrainian wife of the Turkish Sultan Suleiman I the Magnificent . . . had a great influence over the affairs of state” ([487], page 118). A portrait of Roxelana can be seen in fig. 20.16.

In the “ancient” version Roxana, the wife of Alexander the Great, is a Bactrian princess ([1370], page 219). We instantly recollect that, according to Scaligerian history, in the XIII-XIV century Egypt was ruled by the Bakharit Mamelukes, or the Bagherids, and then by Cherkassians ([99], page 745). They identify as the Ottoman Cossacks, or the founders of the Ottoman (Ataman) Empire. In this case the Bactrian princess Roxana is likely to be identified as a Bagherid = Bakharit princess, or a Cossack woman from Russia (or the Horde).

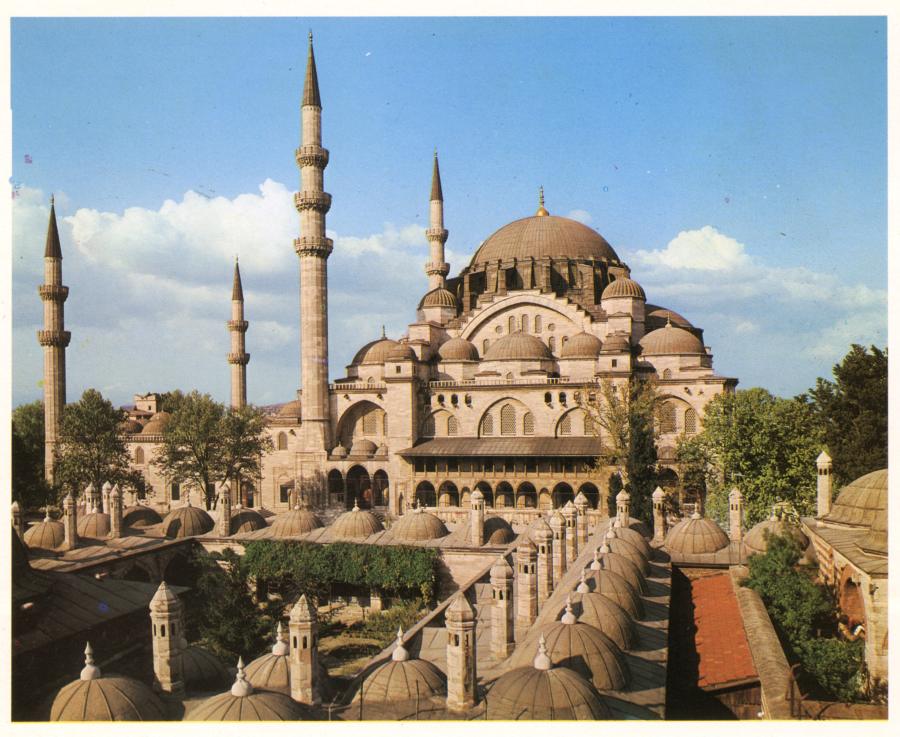

At the centre of Istanbul one finds the enormous mosque of Suleiman I, which was built in the middle of the alleged XVI century A. D. ([1464], page 59). “It is a magnificent construction that towers over the top of the hill overseeing the Golden Horn Bay” ([240], page 242; see fig. 20.17).

Right next to it we find a graveyard, which is believed to be the resting place of “Suleiman I himself and his Russian wife Roxelana” ([1464], page 61; also [1404], pages 554-555). It seems odd that a great conqueror should be buried on a common graveyard, even given that his mausoleum (“turbe” in Turkish) is larger than the rest. It is an octagonal construction with a dome ([240], page 250). The actual sepulchre of Suleiman I (the coffin, that is) is covered in “shawls and embroidered garments of great value” ([240], page 251). Next to the turbe, or sepulchre, of Suleiman I, we find that of “Roxelana, the wife of Suleiman” ([240], page 251).

Taking the above into account, one cannot fail to notice that the splendorous royal palace of Topkapi is located in the immediate vicinity of the mosque of Suleiman I – this is where the luxurious “ancient” sarcophagus of Alexander the Great is kept (see fig. 20.18). Could this be the authentic original sepulchre of Suleiman I?

One way or another, the sarcophagus of Alexander the Great is located in Istanbul, which was the capital of the Great Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. The sarcophagus of Alexander the Great “has the shape of a Greek temple; it is decorated with sculptures” ([1464], page 15). A propos, the famous “ancient” marble bust of Alexander is also kept here (see fig. 20.19).

8. The location of Memphis and Thebes – the capitals of the “ancient” Egypt.

It is believed that the famous cities of Memphis and Thebes were the two capitals of the “ancient” Egypt. It goes without saying that the modern guides have no qualms about showing the tourists the “ruins” of both cities, allegedly located in African Egypt. However, the actual identification of their historical locations is far from being an easy task.

N. A. Morozov writes: “Of course, from the strategic point of view the foundation of the Egyptian capital in this particular place, at the entrance to the delta of the Nile, appears inevitable. The city of Cairo exists here until the present day – had it been identified as the ancient Memphis, one would find it problematic to disagree. However, tradition locates the ancient Memphis some 50 kilometres to the south of Cairo – and on the opposite bank of the Nile to boot, which is a desert by nature. What traces of the city could survive there?” ([544], page 1118).

Egyptologists have long been embarrassed by the fact that the place where they had to draw Memphis on the map “is completely void of anything resembling noticeable ruins of a city”. According to Brugsch, “the only remains of the sometime great and glorious city amount to a pile of rubble left from shattered columns, sculptures and altar stones . . .

Anyone who goes to Memphis in hope to see an area whose very ruins would be worthy of the fame of the famous world centre on the banks of the Nile will be bitterly disappointed by the sight of nondescript rubble and stones.

Only one’s mind’s eye can invoke the whole glory and magnificence of Memphis from the past”, as Brugsh sadly tells us. “One needs to be aware of this if one decides to undertake a journey, or, rather, a pilgrimage to the remains of the ancient capital – the former location of the famous Shrine of Ptah . . . Nowadays it is but a forest of palm trees and a large field cultivated by the fellahin next to the Arabic settlelment of Mit-Rakhine” ([99]. Pages 106-107).

“All the numerous excavations of the soil where the ancient Memphis had stood, aimed at the discovery of monuments possessing some historical significance, haven’t led to any results worthy of mentioning”, as Brugsch dejectedly concludes ([99], page 108).

Being confronted by the necessity of explaining the current whereabouts of the stones, if nothing else, remaining from the allegedly obliterated Memphis the Great, Brugsch proposes the following version: “It appears beyond any doubt [? – Auth.] that the gigantic stones used in the construction of the temple were gradually taken away to Cairo and used for building mosques, palaces and houses of the Caliphs” ([99], page 108).

The situation with the Thebes isn’t any better.

This is how N. A. Morozov summarises the reports of the Egyptologists: “Not a single thing has remained of the city . . . The magnificent remnants of the academic temples of Luxor and Karnak still stand on the Eastern bank of the Nile; they have preserved well. On the other bank we find the remains of the temples of Kurna, Remesseum and Medinet-Abou, still standing tall and also remaining in a good enough condition. Yet there isn’t a single trace of the actual city anywhere – the Thebes of 100 Gates have vanished without a trace!”

Morozov proceeds to report that the city <<is said to have been destroyed at the orders of Ptolemy Soter II Latirus, who reportedly lived 84 years before Christ . . .

Where are the stones, one wonders? Nowhere to be found. It is said that they were washed away by the yearly floods (Mariette, “Monuments”, page 180). Yet has any flood ever managed to wash away stones, as though they were floating logs? . . . Also, who could have come up with the wild idea of building one’s capital on a site where the floods can wash away the very stones?>> ([544], pages 1116-1117).

Given everything that we have found out by now, it would make sense to enquire whether we are actually looking for Memphis, or the famous capital of the “ancient” Egypt, in the correct place? Also – was it actually located in Egypt in the first place? After all, we have seen that the stones of Egypt bear many memories of events from the life of other lands, including Europe, Asia etc.

Firstly, let us pay some attention to the fact that the modern capital of Egypt is called Cairo – a noble name of royal origin, since Cairo = CR = Czar (Caesar).

Other options are also possible. Let us turn to the “ancient” names of Memphis. According to Brugsch, “the most frequently encountered name of the city was Mennofer, as we mention above. The Greeks transformed it into “Memphis”, and the Copts, into Memphi” ([99], page 106). As for the name of the settlement where the “ruins of Memphis” are located today – the “royal” name of Mit-Rakhine must have been given to it for a good reason and already in a later epoch, when the Egyptologists already started their quest for Memphis in Egypt – it is derived from the “ancient” Egyptian name Menat-Ro-Khinnu ([99, page 107).

Considering the sum total of the new information on the “ancient” Egypt that we have obtained, we shouldn’t rule out the possibility that the name Menat-Ro-Khinnu is a derivative of MN-TR-KHAN, which might stand for “The Great Tartar (or Turkish) Khan”. The most common name of the capital (Men-nother) also sounds like MEN-TR, qv above. Could this really be yet another version of “The Great Troy”, or “Mongol Troy”? We are referring to Czar-Grad = New Rome = Biblical Jerusalem = Troy (Trinity)?

The proximity of Troy and the “ancient” Memphis is mentioned by the Egyptologists themselves. According to Brugsch, “the builders quarried for white limestone, which they had used in the construction of the royal pyramids, in the caves of the Taroau Ridge (near Memphis), which the Greeks knew as Troy, and modern Arabs call Tura” ([99], pages 112-113).

There is nothing surprising about this passage if we are to assume that Memphis and Troy were in fact the same city. Later on, their names were falsely indicated on the maps as pertaining to the territory of the modern Egypt – this occurred during the arbitrary relocation of many European and Asian events to these parts (as chronicle records).

Our hypothesis can be formulated in the following way. The “ancient” Memphis can be identified as Czar-Grad, of the Great Troy. The city exists until the present day – we know it as Istanbul. During certain periods of its history it was indeed the city of the Khans, and for a long while, at that – this goes to say that it was ruled by the Ataman Cossack Khans. This provides an instant explanation to the “strange” fact that no visible ruins of Memphis have been found anywhere in African Egypt to this very day.

We have reached the end of the famous 18th Dynasty of the “ancient” Egypt, or the XVI century A. D., as we have discovered. This epoch marks the end of the Pharaohs’ “ancient” history.

9. Conclusion.

We have merely analysed a couple of the “ancient” Egyptian dynasties (out of 30). Nevertheless, we have concentrated on the most famous ones – the dynasties that were mentioned the most often in the historical sources. Indeed, the fundamental work of Brugsch entitled “History of the Pharaohs” ([99]), which provides a consecutive description of all 30 dynasties based on the surviving “ancient” Egyptian texts, devotes about a half of its entire volume to the to the events of the Hiksos epoch (the 18th and the 19th dynasties), minus the introduction and the annexes. Therefore, even a cursory glance at the book of Brugsch reveals the importance of the epoch that we have just covered to the Egyptologists.

As we see, other dynasties are covered in documents to a much lesser extent. We shall withhold from studying them in detail presently, and merely formulate the hypothesis that they are also phantom reflections, or duplicates of the XIV-XVII century epoch.