Part 2.

China. The new chronology and conception of Chinese history. Our hypothesis.

Chapter 5.

Chinese comets.

1. Suspiciously high comet observation frequency in China.

Above we have told about the sources that recorded the observations of Chinese comets. By a “Chinese” comet we mean a comet observation recorded in a certain chronicle identified as Chinese nowadays.

The complete roster of Chinese comets contains over 300 records. It is presumed that these records report observations of comets that took place in 309 different years. Nowadays historians distribute them over the interval between 610 B. C. and 1640 A. D. Thus, the roster covers the span of some 2200 years, which gives us about one comet observed in seven years. However, since the comet roster contains a number of lacunae, since there are epochs when no comet observations were recorded, the frequency of comet observation in China is much higher – a comet in every three years for some epochs, for instance. In the III century A. D. the Chinese observed 35 comets, and 20 of them in the IV century.

Apart from that, all these comets are presumed to have been visible to the naked eye, since they’re mentioned in chronicles, which often contain personal impressions of the chroniclers, and not specialised astronomical literature. It would be natural to assume that comets mentioned in chronicles were quite spectacular and visible to many people.

This makes the Chinese comet roster very odd indeed. The frequency of comet observations recorded therein is very high, even if we’re to assume that the Chinese didn’t merely mention spectacular comets, but also tiny ones, which would appear as a minute point to the naked eye.

How many comets have modern readers seen in their lifetime? Not a single truly spectacular one over the last fifty years. There were small comets, which could be seen to the naked eye after their prior location on the sky with the use of a telescope. However, the ancient Chinese are unlikely to have used powerful telescopes in order to rake through every sector of the sky in order to find a comet and instantly write it into a chronicle.

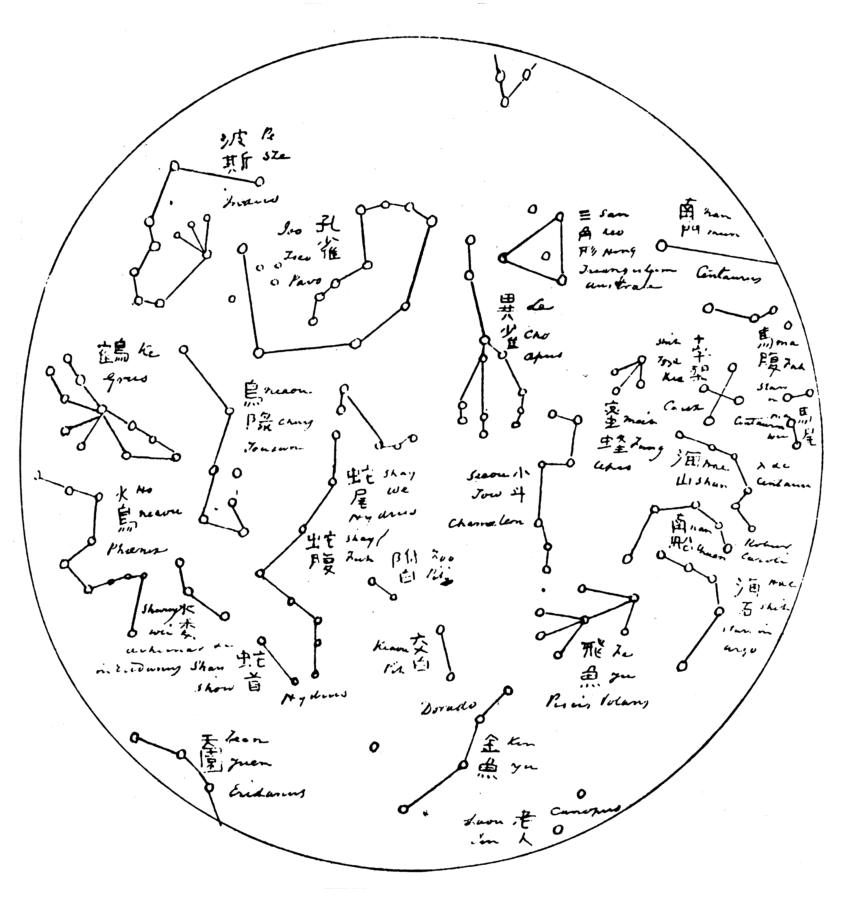

Fig. 5.1. Chinese star chart of the XIX century. Northern Hemisphere. The map is very primitive. Taken from [544], Volume 6, page 64.

Fig. 5.2. Chinese star chart of the XIX century. Southern Hemisphere. N. A. Morozov wrote the following about these star charts: “In order to picture just how naïve Chinese astronomy was as recently as in the XIX century, I suggest to consider the following six star charts from the book of John Williams . . . The readers shall instantly recognize . . . Ursa Major, but that is the only constellation here that looks familiar. Nearly every constellation looks untypical; also, the lack of a coordinate grid leads to an almost childishly naïve disposition of star configurations that renders them unidentifiable in most cases” ([544], Volume 6, pages 64 and 69). Taken from [544], Volume 6, page 69.

Moreover, in order to distinguish between a small comet and a star the Chinese needed a full catalogue of visible stars in order to locate a slowly moving dot of a comet among them. Let us consider the star charts used by the Chinese astronomers. What do we see? In figs. 5.1 and 5.2 we reproduce a Chinese star chart of the XIX century as an example. Even this chart is rather primitive, and it dates from the XIX century. N. A. Morozov also cites the ancient Chinese star catalogues of the XIX century ([544], Volume 6). They are rather primitive, crude and incomplete.

N. A. Morozov wrote the following in this respect: “It is plainly obvious to the reader that almost all of the untypical stellar combinations are distributed in a childishly naïve manner due to the lack of a grid [in the XIX century, no less! – Auth.], which often makes it impossible to identify them as real stellar configurations” ([544], Volume 6, page 69).

We are supposed to believe that these “childishly naïve” astronomers successfully discovered a comet almost every three years. This frequency implies most of them to have been hardly observable dots. One must observe such a dot for many days on end to discover its slow motion across the sky and identify it as a comet. Apart from that, this dot needs to be found first – it is easy to speak about it now, when the sky is constantly combed through by telescopes.

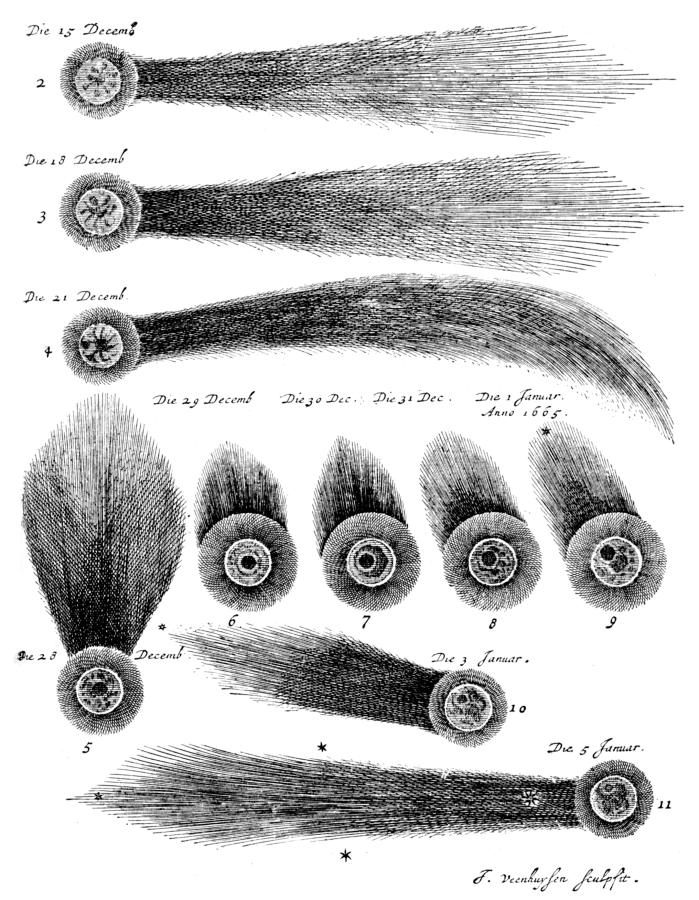

Fig. 5.3. Several ancient drawings of comets from S. Lubieniecki’s “Theatrum Cometicum” dating from 1681. The very nature of the drawings demonstrates that all the comets were observed with the naked eye. Book archive of Pulkovo Observatory, St. Petersburg. Taken from [543], page 201.

Fig. 5.4. Chinese drawing of a comet near the constellation of Ursa Major.

Taken from [544], Volume 6, page 70.

These considerations make us admit that the Chinese comet roster looks exceptionally strange. N. A. Morozov was perfectly correct to write: “Our modern and exact knowledge of the amount of comets visible to the naked eye registered over the last three centuries make it perfectly obvious that these interstellar vagabonds don’t quite rain over us in such abundance as one finds in the roster [of Chinese comets – Auth.]” ([544], Volume 6, page 60).

In fig. 5.3 we reproduce some drawings of comets from an ancient book of Stanislaw Lubieniecki dating from 1681. In fig. 5.4 we see an ancient Chinese drawing of a comet next to Ursa Major.

2. Years of comet observations in China.

A list of Scaligerian dates when alleged comet observations are registered in Chinese sources (also given in [544], Volume 6, pages 130-132).

-610,

-530, -515, -501,

-466, -432,

-304, -302,

-295, -239, -237, -233, -232, -213, -203,

-171, -156, -154, -153, -147, -146, -137, -136, -134, -133, -119,

-118, -109, -108,

-86, -83, -76, -75, -73, -72, -71, -69, -68, -60, -48, -47, -43,

-31, -11, -4, -3,

13, 22, 39, 55, 60, 61, 65, 66, 71, 75, 76, 77, 84,

102, 110, 131, 141, 147, 148, 149, 161, 178, 180, 182, 185, 188,

192, 193,

200, 204, 206, 207, 213, 218, 222, 225, 232, 236, 238, 240, 245,

247, 248, 251, 252, 253, 255, 257, 259, 262, 265, 268, 275, 276,

277, 279, 281, 283, 287, 290, 296,

300, 301, 302, 303, 304, 305, 329, 336, 340, 343, 349, 358, 363,

369, 373, 386, 390, 393,

400, 401, 402, 415, 416, 418, 419, 422, 423, 442, 449, 451,

501, 532, 539, 560, 561, 565, 568, 574, 575, 588, 594,

607, 615, 616, 626, 634, 639, 641, 663, 667, 676, 681, 683, 684,

707, 708, 710, 713, 730, 739, 760, 767, 770, 773,

815, 817, 821, 828, 829, 834, 837, 838, 839, 840, 841, 851, 856,

864, 868, 869, 877, 885, 886, 892, 893, 894,

905, 912, 928, 936, 941, 943, 956, 975, 989, 998,

1003, 1014, 1018, 1035, 1036, 1049, 1056, 1066, 1080, 1095, 1097,

1106, 1110, 1126, 1131, 1132, 1133, 1145, 1147, 1151

1222, 1226, 1232, 1237, 1240, 1264, 1277, 1293, 1299,

1301, 1304, 1313, 1315, 1337, 1340, 1351, 1356, 1360, 1362,

1363, 1366, 1368, 1373, 1376, 1378, 1385, 1388, 1391,

1407, 1430, 1431, 1432, 1433, 1439, 1444, 1449, 1450, 1452, 1453,

1456, 1457, 1458, 1461, 1462, 1465, 1468, 1472, 1490, 1491, 1495,

1499,

1500, 1502, 1506, 1520, 1521, 1523, 1529, 1531, 1532, 1533, 1534,

1536, 1539, 1545, 1554, 1556, 1557, 1569, 1577, 1578, 1580, 1582,

1584, 1585, 1591, 1593, 1596,

1604, 1607, 1609, 1618, 1619, 1621 1639, 1640.

1) We have omitted sightings of several comets in a single year – for instance, it is presumed that the Chinese observed three comets in 416 A. D., two comes in 422 A. D. and so on. All such multiple records are omitted.

2) We do not cite the data concerning precise calendar dates of presumed comet observations. The Chinese have left records that report the exact year, month and sometimes even day when a given comet was observed, presumably of the highest exactitude. We shall not require these data; moreover, we shall see that all of these “exact indications” are likely to date from a rather recent epoch.

3) Many Chinese records specify paths of comets across different constellations. We do not cite these data here for the following reason. The analysis of these paths only make sense if we need to estimate the orbits of these comets or want to identify them as comets that we already know. The only comet that it is sensible to identify in this manner is the famous Comet Halley. However, we shall consider it specifically later on. As for all the other comets, we have to point out the following: “Apart from Comet Halley, we know of no other recurrent comets visible to the naked eye that would confirm the precision of European and Chinese reports. The recurrence of many comets, most of them minute, has been estimated by now; however, not one of them is mentioned in the chronicles in such a manner that it could be identified” ([544], Volume 6, page 156).

3. European comets and their observation dates.

A list of Scaligerian dates when the alleged sightings of comets were recorded in European chronicles (also given in [544], Volume 6, pages 130-132).

-479, -465, -430, -429, -413, -411, -409,

-372, -352, -347, -340, -335,

-219 (?), -203,

-199, -182, -167, -165, -164, -149, -145, -143, -135, -128, -118,

-117, -116, -109,

-98, -92, -89, -86, -83, -39, -59, -46, -45, -44, -42, -40, -30,

-29, -28, -22, -12,

12, 14, 16, 17, 40, 48, 51, 54, 56, 57, 60, 61, 62, 66, 68, 69,

70, 72, 73, 76, 78, 79, 81,

130, 145, 146, 160, 161, 181, 188, 190, 192, 195,

204, 213, 217, 220,

307, 308, 324, 335, 340, 363, 367, 370, 375, 377, 380, 383, 384,

386, 389, 390, 393, 394, 396, 399,

405, 410, 412, 413, 418, 423, 434, 442, 443, 448, 450, 453, 454,

457, 459, 488,

500, 519, 531, 533, 535, 538, 540, 541, 550, 557, 560, 570, 583,

587, 589, 594, 597, 599,

601, 602, 603, 604, 607, 617, 620, 622, 623, 631, 633, 660, 667,

674, 675, 676, 678, 684, 685, 687,

715, 719, 729, 744, 745, 761, 763, 791,

800, 809, 812, 814, 815, 817, 818, 828, 819, 830, 837, 838, 839,

840, 841, 844, 868, 876, 882,

900, 902, 905, 906, 910, 912, 913, 930, 941, 942, 944, 964, 968,

975, 979, 983, 996, 999,

1000, 1004, 1005, 1006, 1009, 1017, 1027, 1031, 1038, 1042, 1053,

1058, 1064, 1066, 1067, 1071, 1077, 1092, 1095, 1097, 1098,

1102, 1103, 1106, 1107, 1108, 1109, 1110, 1111, 1112, 1113, 1119,

1125, 1132, 1133, 1141, 1145, 1163, 1169, 1172, 1180,

1200, 1202, 1211, 1214, 1213, 1217, 1219, 1222, 1223, 1230, 1238,

1240, 1241, 1254, 1255, 1256, 1264, 1267, 1268, 1269, 1273, 1282,

1285, 1286, 1293, 1298, 1299,

1300, 1301, 1302, 1303, 1307, 1312, 1313, 1314, 1315, 1318, 1337,

1338, 1339, 1340, 1341, 1345, 1347, 1351, 1352, 1353, 1362, 1363,

1365, 1368, 1376, 1379, 1380, 1382, 1390, 1391, 1394, 1399,

1400, 1401, 1402, 1403, 1407, 1408, 1414, 1426, 1433, 1434, 1439,

1444, 1445, 1450, 1454, 1456, 1457, 1458, 1460, 1461, 1467, 1468,

1470, 1471, 1472, 1475, 1476, 1477, 1491, 1492, 1493,

1500, 1504, 1505, 1506, 1510, 1511, 1512, 1513, 1514, 1516, 1517,

1521, 1522, 1523, 1524, 1526, 1527, 1528, 1529, 1530, 1531, 1532,

1533, 1537, 1538, 1539, 1541, 1542, 1545, 1554, 1556, 1557, 1558,

1559, 1560, 1564, 1566, 1569, 1572, 1576, 1577, 1578, 1580, 1582,

1583, 1585, 1590, 1593, 1596, 1597,

1602, 1604, 1607, 1618, 1652, 1653, 1661, 1664, 1665, 1682.

Apparently, the European list also provokes many confused questions. Nearly every oddity pointed out in Chinese rosters is also present here.

Furthermore, one cannot fail to notice the amazing multitudes of comets that Europeans are believed to have observed in the Middle Ages. Take the part of the roster corresponding to the XVI century, for instance. See for yourselves:

4 comets were observed in 1500,

2 comets were observed in 1504,

6 (!) comets were observed in 1506,

3 comets were observed in 1511,

3 comets were observed in 1516,

2 comets were observed in 1523,

4 comets were observed in 1527,

3 comets were observed in 1529,

4 comets were observed in 1530,

6 (!) comets were observed in 1531,

6 (!) comets were observed in 1532,

5 (!) comets were observed in 1533,

3 comets were observed in 1538,

6 (!) comets were observed in 1539,

2 comets were observed in 1541,

3 comets were observed in 1542,

2 comets were observed in 1545,

8 (!) comets were observed in 1556,

3 comets were observed in 1557,

6 (!) comets were observed in 1558,

2 comets were observed in 1560,

3 comets were observed in 1569,

6 (!) comets were observed in 1572,

2 comets were observed in 1576,

9 (!!) comets were observed in 1577.

And so on, and so forth (see [544]).

It appears that in the XVI century Europeans are said to have observed 145 comets with the naked eye. This is completely out of proportion. Let us remind the readers that the telescope was only invented in the XVII century – therefore, one can only speak of comets visible with the naked eye, and those are very scarce indeed.

N. A. Morozov was perfectly correct to note: “European comets observed with the naked eye are so abundant that no such observations must ever have taken place” ([544], Volume 6, page 135). The comet roster cited above brings us to the following conclusion.

It is most likely that we are confronted with various reports of a single comet, which were later presumed to refer to different comets. This also demonstrates that many mediaeval records were misdated by later chronologists, who have transformed a single comet into a multitude which became spread over many years. Once again, this proves that a correct conversion of a date found in a mediaeval document into the modern chronological system is anything but a simple task. At any rate, we can see that mediaeval chronologists have made a great many mistakes.

Alternatively, we shall have to assume that in the XVI century one could indeed observe comets with the naked eye nearly every month.

One might suggest that the chronologists could be corrected – for this end, we should collate different descriptions of a single comet into one and create a correct comet chronology.

Unfortunately, this would only be possible if we knew the dates when said comets could be observed in reality a priori. The problem is that we know no such dates; this is precisely what we have to find out from the roster that we have at our disposal today.

We can see that the astronomers and cometographers of the XVII-XVIII century could not distinguish between the “fictitious comets” and real ones, or identify various descriptions of a single comet as such. It is easy enough to understand why – various eyewitnesses of a single comet could describe it differently (for instance, confusing the constellations that lay in the path of the comet). Different trajectories were recorded as a result. Mediaeval cometographers were apparently unable to take their bearings in the resulting chaos of data. Chances are, it is impossible to reconstruct the veracious chronology of mediaeval comet observations.

One of the implications is that the years of comet observations reported by mediaeval chronologists, let alone the months, cannot be considered reliable datings.

References to the constellations that lay in the path of the comet are also unreliable – especially seeing as how it is highly unlikely that all mediaeval citizens had star charts at their disposal (Dürer’s, for instance), which would give them an opportunity of tracing the comet’s path – therefore, it could only be traced by professional astronomers. However, we see that even they often got confused. Let us, for instance, consider the European description of the path of Comet Halley in the alleged year 1378 A. D. ([544], Volume 6, page 142). Initially it strikes one as a natural description of a comet’s trajectory across constellations. However, a closer study reveals that “the comet’s position fitted the purpose of calculating its orbit so poorly that Pingré declared it useful for nothing but tiring the very heart out of an overly diligent researcher of Comet Halley” ([544], page 142). Apparently, the mediaeval observers muddled something up, and it is impossible to estimate the exact nature of their error nowadays.

4. A comparison of the Chinese and European comet rosters.

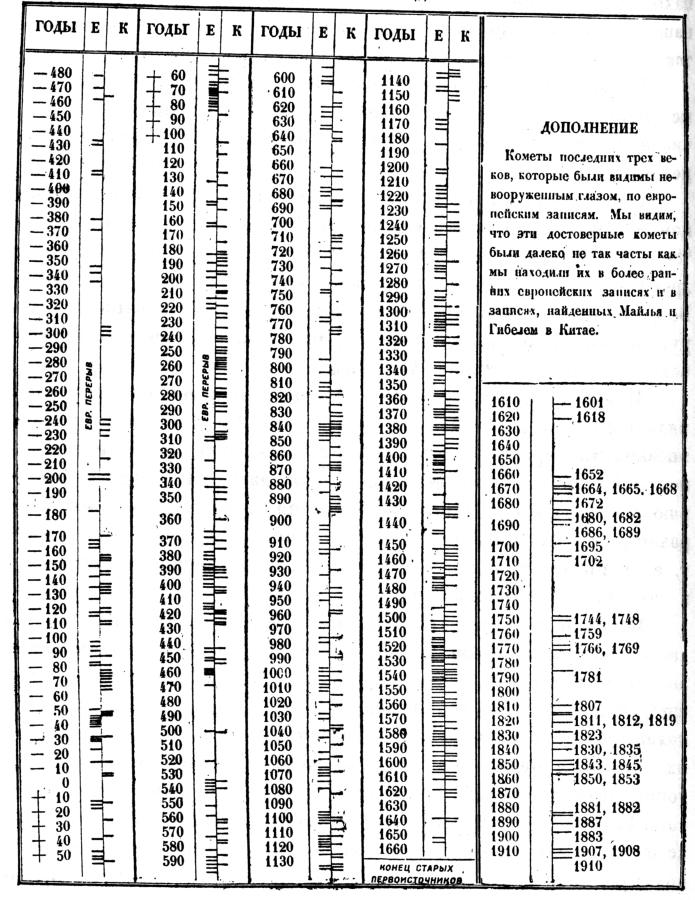

Fig. 5.5. Table from N. A. Morozov’s book ([544], Volume 6, page 168) that reveals the existence of serious contradictions within and between the “ancient” Chinese and the “ancient” European comet rosters.

Let us sum up. N. A. Morozov compiled comparative dating tables for the Chinese and European records of comet sightings ([544], Volume 6, pages 130-132). He discovered that the “ancient” Chinese comet observations fail to concur with the “ancient” European observations. Both rosters (the “ancient” Chinese and the “ancient” European) are too dense. Such great density of comets visible to the naked eye is impossible. Both these facts are made obvious by the table compiled by N. A. Morozov, which is reproduced in fig. 5.5. Dashes to the left of the middle lines correspond to the years of “comet sightings” in European sources, and dashes to the right represent the Chinese. The right part of the table corresponds to the years between 1610 and 1910 when comets visible to the naked eye were observed veritably.

It is plainly visible that the density of dashes in the veracity zone of the last few centuries is much lower than what we see in the “original ancient sources”, Chinese as well as European. The lack of concordance between the dashes in the left and right parts demonstrates that the “ancient” Chinese and the “ancient” European rosters do not concur with each other, which makes one doubt their veracity. It is obvious that the Europeans and the Chinese must have observed the same comets in the sky. If we’re to assume that the Europeans only registered one half of all comets, and the Chinese, the other, the frequency of “ancient” comet observations shall become completely implausible.

The corollary of N. A. Morozov based on the analysis of the resultant summary tables X and XIII is as follows (see [544], Volume 6, pages 130-132 and 168).

“Let us consider the chronological likeness of the Chinese and European reports. I am referring to correspondence in dates exclusively, without taking the actual descriptions of comets into consideration, since we won’t be able to find a single European comet whose description will resemble that of its Chinese counterpart up until the arrival of the Catholic missionaries to China. The extent of correspondence between the respective dates can be judged by the readers from the following table [see [544], Volume 6, pages 130-132 – Auth.] – I also included all the dubious comets as registered in the Chinese chronicles, and everything I could find in Lubieniecki’s ‘Theatrum Cometicum’ [the famous mediaeval ‘Cometography’, or a catalogue of 1681 – Auth.] for the European chronicles.

The situation with the B. C. comets is truly astounding. There is chance coincidence between the comets of 109, 86 and 83 B. C., whereas the datings of all the other comets are diverse to the following extent. Whenever we see Chinese records, their European counterparts are missing, and vice versa: large arrays of European records aren’t matched with any Chinese sources. The Europeans contradict the Chinese, and the Chinese contradict the Europeans . . .

Let us now regard the period between the beginning of the new era and the ascension of Constantine (0-306 A. D.). We see the same chaotic leapfrog of Chinese and European datings up until Alexander Severus (222 A. D.) . . . The 85-year interval between the respective ascensions of Alexander Severus and Constantine to the throne is even more spectacular. Chinese reports indicate 38 comet observations for this period; European chronicles mention none, save for the vague report of some occurrence that dates from 252 A. D. . . . However, the leapfrog of the Chinese and European dates continues after this period, the sole difference being that they become more numerous and thus more susceptible to random coincidence . . . The correspondence between the two only becomes regular enough to stop resembling random coincidence in the XII century” ([544], Volume 6, pages 133-134).

This leads us to one of the following conclusions:

1) The consensual datings of Chinese comet observations before the XIII century A. D. are incorrect.

2) The consensual datings of European comet observations before the XIII century A. D. are incorrect.

3) Both are incorrect.

We believe the latter to be the case.