Chapter 11.

Mediaeval Scandinavian maps and geographical oeuvres report the “Mongolian” conquest of Eurasia and Africa.

1. A general characteristic of geographical tractates.

1.1. The time most Scandinavian tractates on geography were written.

In the present chapter we shall be referring to the research of Y. A. Melnikova as covered in [523], wherein she provides the results of her study of a great many Scandinavian maps and works on geography. Her book gives us access to many rare mediaeval materials, which turned out to bear direct relation to our reconstruction of global history. The information related by the mediaeval Scandinavian geographers has survived, fortunately enough. Basically, much of the information contained in those sources is in perfect correspondence with our reconstruction. Naturally enough, it is anything but easy to notice – one needs to delve into an array of formal materials that initially strike one as tedious – maps covered in names, involved geographical ruminations and so forth. Anything but an easy read, in other words.

We have therefore done the following. We have systematised the historical and geographical information from Scandinavian sources and compiled a table of emerging mediaeval geographical identifications, basing it on the abovementioned book of Y. A. Melnikova entitled “The Geographical Works of the Ancient Scandinavia” ([523]). The resulting table can be found at the end of the present book. The readers are free to use it for drawing their own conclusions. For the meantime, we shall merely tell about the conquest of the world and the identity of the conquerors as described by Scandinavian geographers.

Let us begin with relating the contents of Y. A. Melnikova’s work in more detail. Her book contains actual mediaeval Scandinavian texts as both originals and Russian translations, which reflect the Scandinavian conceptions of the geography of the world, primarily the regions adjacent to Scandinavia.

It turns out that there are no written Scandinavian geographical sources in existence that would predate the XII century. Y. A. Melnikova acknowledges that “although this knowledge did not exist in the written form before the XII century, it had been kept alive by the populace” ([523], page 28).

The second half of her phrase is the already well familiar abstract hypothesis concerning “oral tradition” favoured by historians, similar to that about the poems of Homer, equalling some 700 pages of text in a modern book in volume, learnt by heart by generations of sheepherders and kept alive in popular memory for several centuries before they were finally set down in writing, qv in CHRON2, Chapter 2:5.1. We are of the opinion that no real preservation of information is possible in absense of written documents.

Let us however make the note about the “ancient” Scandinavian works on geography dating from the XIII century A. D. and not any earlier. This is in perfect correspondence with our new conception of the ancient and mediaeval history. Moreover, it turns out that the mediaeval Scandinavian historical tractates didn’t surface before the XVIII century.

This is why the maps attached to them must have been compiled a great deal later than what is generally assumed today – in the XV-XVII century, perhaps, but by no means in the XIII-XVII.

Indeed, this is what we learn from the historians themselves: “One of the general descriptions of the world was first introduced into academic circulation by J. Langebeck in 1773 . . . In 1821 [already in the XIX century, that is – Auth.] the first compilation of the ancient Icelandic geographical oeuvres came out, prepared by E. Werlauf . . . Werlauf accounts for the four primary handwritten collections in his publication, but doesn’t use the entire volume of materials contained in them” ([523], page 16). Further also: “K. Ravn contributed greatly to the expansion of the pool of the ancient Scandinavian works of literature, who had published fragments of the majority of tractates on the history of the Ancient Russia (1852) as well as their Latin translations” ([523], page 16).

Thus, the whole bulk of this Scandinavian information actually surfaced in the XVIII-XIX century. Therefore, authentic historical data contained in the tractates listed above are already covered by a thick layer of Scaligerian history. This must be constantly borne in mind during the research of the mediaeval geographical texts, and surviving mediaeval chronicles in general.

Basically, any statement along the lines of “such-and-such ancient oeuvre tells us of this, that and the other” only begins to make sense in chronological terms once we find the answer to the following question: when was this allegedly ancient text written? Our further attitude to the information contained in the source in question should be wholly dependent on the answer to this question.

If we don’t manage to trace the fate of a given text any further back than the XVII century A. D., the reason must be that it was written in the XVI-XVII century or slightly earlier than that, and therefore covered by a thick layer of Scaligerian sediment.

Let us note that the majority of the ancient texts are believed to be of a mind-boggling age; however, most of them cannot be traced any further back in time than the epoch of the XVI-XVII century, which is when they were written, or have undergone the final edition at the very least. At best, what we have at our disposal amounts to post-Scaligerian editions of most ancient texts. It is important that we realise one thing: any claim about the existence of a given text before the epoch of the XVI-XVII century needs special proof today.

Scandinavian scribes were rather accurate with their chronology. They started the documented history of their countries from the X-XI century A. D., without inventing any figmental “ancient Scandinavian epochs”. However, we shall refrain from tackling the issue about just how valid the early dates of Scandinavian history really are for the time being (they are attributed to the X-XIII century A. D. nowadays). As we have come to realise, we shall not be likely to find any real information about the epochs predating the XIII-XIV century.

The fact that the final editions of the Scandinavian tractates must be dating from the XVII-XVIII century could not fail to affect the nature of their rendition. The influence of the erroneous Scaligerian chronology was inevitable, and must have affected them greatly. However, we can already try to separate real historical facts from the Scaligerian sediment, using the results of our research, among other things.

We know the following about the Scandinavian geographical tractates. According to Y. A. Melnikova, “In the XIII-XIV century these works were tremendously popular – in Iceland, first and foremost. They have been copied and reworked a great many times, and also included into special compilations – the “encyclopaedias” . . . that came before the chronicles and the annals. More than 20 manuscripts that include geographical tractates and maps have survived until our day: 8 of them date from the XIII-XV century, 1 – from the XVI century, 5 – from the XVII century and 7 – from the XVIII century. Apart from that, we have a number of XIV-XVII century manuscripts at our disposal, which contain the Norwegian translation of the Bible with an extensive geographical description . . .

They are based on the immediate familiarity of the Scandinavians with the Ancient Russia . . . [They] also shed some light over some important historical moments in the life of the ancient Russian kingdom” ([523], page 5).

The words of Y. A. Melnikova turn out prophetic, although she means it in a less explicit way than we do. As we shall see, geographical tractates from Scandinavia do indeed pour a great amount of unexpectedly bright light over the history of the Ancient Russia.

1.2. The physical appearance of the first maps.

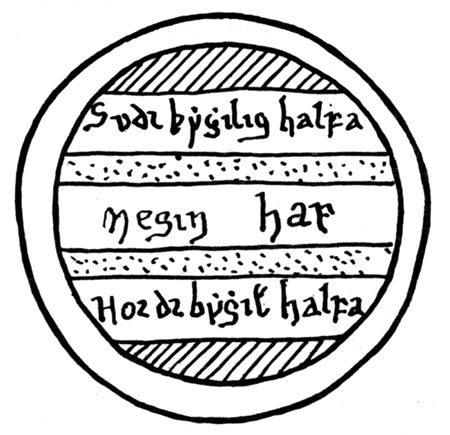

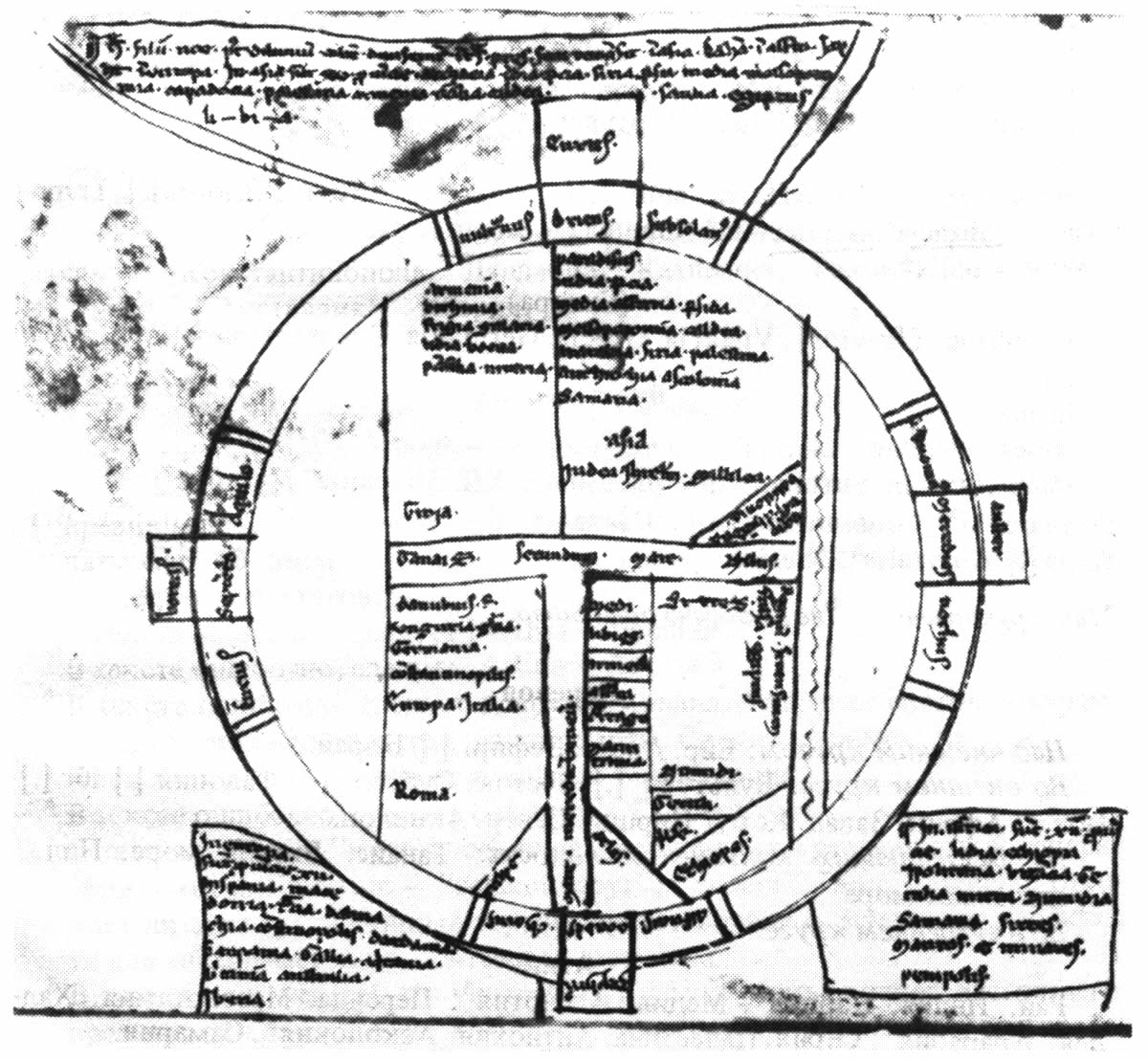

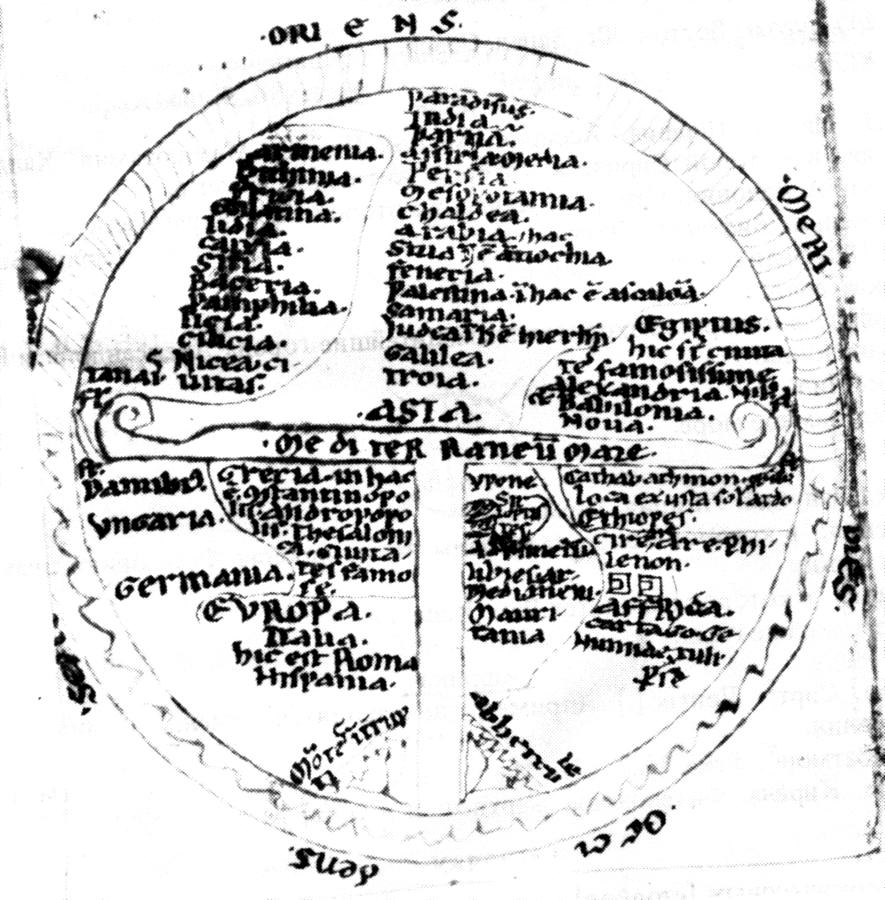

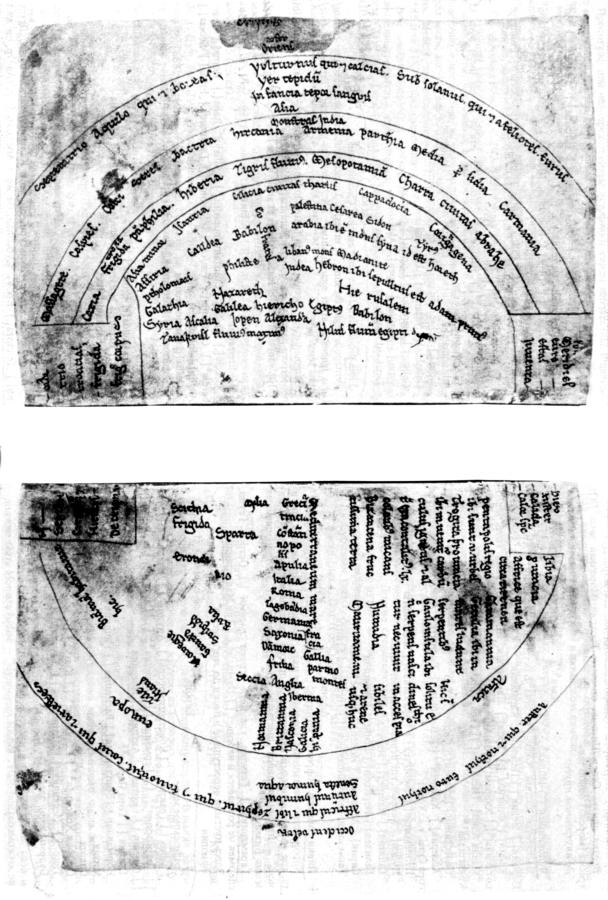

Scandinavian maps of the XIII-XVII century as applied to geographical tractates are still a far cry from their modern equivalents. Moreover, quite often they aren’t actual maps in the modern meaning of the word. Even their outwardly appearance is drastically different from what we’re accustomed to associate with geographical maps. They were usually drawn in a circular shape, divided into several parts by straight lines, with a list of countries included in a given part of the world inside each segment.

Such maps are therefore lists of geographical names rather than maps – they are distributed across the three parts of the world, namely, Asia, Europe and Africa. In figs. 11.1, 11.2, 11.3, 11.4, 11.5 and 11.6 the reader can see a couple of such maps. Incidentally, the globe is divided into three parts with the aid of a Christian T-shaped cross on quite a few of them.

The important thing is that the maps we see before us are really very old – they correspond to the very dawn of the European cartography starting with the XIII-XV century. These maps are still very approximate and abstract. These maps are hardly of any interest to us insofar as graphical representations of countries are concerned – those are very often nonexistent. Our attention is really drawn to the lists of countries and cities, as well as the indications of borders, population and migrations.

1.3. The same name with slight variations can be found all across the world on the map.

Names, whether personal or geographical, were more prone to keeping their consonants intact than their vowels as they transformed. One of the reasons behind this effect is that the ancients often omitted vocalizations from their transcriptions of names, using nothing but the consonants. Vowels are a later addition, often made on the basis of a priori hypotheses concerning the geographical localisation of a given text or its dating. Therefore, the consonant skeletons are of a particular interest to us.

For instance, the names Galicia, Galatia and Gaul have similar consonant skeletons, namely, GLC, GLT and GL.

1) Galatia = Galaciam = Galacia = Galathia = Galatina = Gulatia is an area in the centre of Asia Minor ([523], page 204).

2) Galicia, Galacia or Galizo is an area in the North of Spain ([523], page 204).

3) Galilea, Gallilea or Galilee is an area in modern Palestine ([523], page 204).

4) Gallia = Gaul, a Roman province on the territory of modern France ([523], page 204).

5) Galacia, or Gallacia = Russia of Galitsk and Volynsk, and also the Galich Principality in the region of Upper Volga. Let us also recollect the city of Galich (see [517] and the glossary table that we have compiled in accordance with the materials of V. I. Matouzova as cited in CHRON4, Chapter 15:1.5.

Therefore, if some source tells us about the events that took place in a certain land of GLL (unvocalized), we have to make it absolutely clear whether the area in question locates in Spain, Asia Minor, France, Galitsk and Volynsk Russia, or the Galich Principality.

The example that we have cited might give one a rough idea of just how much our understanding of history depends on the correct geographical localisation of the ancient events.

We must also remember that some nations (Europeans, for instance) read text from left to right, whereas others favour the reverse direction (the Arabs etc). One also has to bear this in mind during the analysis of the ancient names, geographical as well as personal.

Apart from that, many of the most important mediaeval geographical names would drift across the map over the course of time. As a result, we have to deal with the following effects today.

1) On the one hand, the same name could be used for referring to different geographical regions in different historical epochs.

2) On the other hand, a single country could be known under a variety of names.

The same refers to the names of nations, cities, rivers etc.

1.4. The multiplication of names on the world map: when and how did it happen?

The example with Galicia as cited above is far from being the only one. There are many of them. In particular, we shall cite a large number of such examples at the end of the present book. This effect becomes less and less pronounced today, which is why we have to turn to mediaeval sources for better representation. The similarities between many names localised in different parts of Eurasia (often located at a great distance from each other), Africa and America are manifest to a much greater extent. These similarities eventually became erased from memory.

The name Ross disappeared from the map of Britain, qv in the geographical atlases of the XVIII century ([1018] and [1019]) as mentioned in CHRON4.

Nowadays it becomes more and more difficult to find the name Rousillon on the map of the South of France, while France itself is no longer known as Gaul (the same as Galatia), which was the case in the Middle Ages.

The name Persia is also absent from the modern map, replaced by Iran. However, mediaeval maps depicted Persia, Paris, Prussia and B-Russia (or White Russia). There was also the word Pars, which used to refer to a large region or country in the XVI-XVII century ([1018] and [1019]). It must have applied to different parts of White Russia, or P-Russia, originally.

The mediaeval Italian Palestrina disappeared from modern maps, giving way to Palestine in the Middle East. This name must have appeared here in the XVII-XVIII century the earliest.

The Kingdom of Jerusalem on the Cyprus is also no longer present on modern maps.

The modern map of Russia won’t tell us anything about the large Galich Principality on the Volga (or the same old Galatia), yet it had still existed in the map of the XVIII century.

The former name of Russia used by foreigners (The Great Tartary) cannot be found in any modern map.

We could have stretched this list onto several pages. More details can be found in the section at the end of the book.

The actual process of information becoming forgotten and desynchronised is perfectly natural. The loss and the permutations of information occur independently in different countries.

However, in this case we are confronted by an important question. When and how did such amazing uniformity of names manifest in the mediaeval world, given the imperfection of the communication means used in that epoch? It appears to have been the result of some relatively short-termed “geographical explosion”, which has scattered multiple copies of a single name all across the world map. The uniformity has eventually become obliterated due to the independence of local changes from each other.

What “explosion” could have caused this? One may come up with all sorts of explanations – however, our new conception appears to provide an exhaustive answer. The “Mongolian” conquest took place in the XIV century, engulfing virtually the whole of Eurasia and a substantial part of Africa, as well as both Americas in the XV-XVI century, qv in CHRON6. The actual conquest of Eurasia (unlike that of America) is recognised by Scaligerian history, although misdated a hundred years backwards. However, this conquest, or colonisation, is presented as the invasion of wild nomadic tribes, incapable of influencing the culture of the conquered lands in any way at all (in particular, this incapability concerns the expansion of geographical names and other terms). It is presumed that the Eurasian and African countries conquered by the “Mongols” did not feel any cultural influence from the part of the latter – on the contrary, the “Mongols” are supposed to have been influenced by the cultures that were alien to them – Russian culture for the most part, since their “base” is believed to have located in Russia.

Our conception changes this point of view completely. The “Mongol” conquest, which was Russian and Turkic for the most part, was obviously a great cultural influence over the conquered nations. In particular, it could have made similar geographical names spread all across the world map. This makes it clear just why the geographical tractates and maps of the XV-XVIII century still remember these common names so vividly – names coined in the XIV century as per our reconstruction.

1.5. A useful alphabetic list of geographical names and their identifications compiled by the authors from Scandinavian tractates and names.

We shall hardly be adding anything to the following text, simply systematising the important information concerning the data gathered from the Scandinavian maps and geographical tractates.

Y. A. Melnikova has conducted a great body of useful work, having collected assorted mediaeval evidence concerning the origins and the migrations of nations and pointed out different identifications of geographical names either contained in Scandinavian tractates or directly implied thereby. They turn out to confirm our reconstruction of world history for the most part.

What actions of ours were innovative as compared to Y. A. Melnikova?

1) We have gathered and systematised the main Scandinavian evidence concerning the propagation of the nations, their origins and the relations between them as a single alphabetic table. It comprises a whole chapter at the end of the present book. As a result, we came up with an alphabetic list, with each section corresponding to the information about one nation or another, its habitat, conquerors (or conquered nations) etc.

2) Various names of this nation as known to the Scandinavians. As a result, it turned out that some peoples and the countries they inhabited had a variety of different names as used in one or another geographical tractate. All such identifications (discovered by ourselves as well as Y. A. Melnikova) were also indicated in our table.

Moreover, we have complemented the analysis of Y. A. Melnikova with the following method, formal but useful. If some mediaeval geographical tractate tells us that the land of A was also known as B, for instance, and another one mentions that the land of B was also known as C, we register this fact in the table as “group equality” (A = B = C). As a result, we have managed to collect all the different names used for referring to the peoples and the countries they inhabited as found in different geographical tractates.

We believe this systematic approach to be inevitable, since random unorganised wallowing through numerous geographical names and their synonyms is the surest way to get confused and ignore any regular pattern there might be. However, it turns out that regular patters do exist; still, they can only be seen once we collect the whole bulk of available material together, if only as an approximated list, so as to get the opportunity of evaluating the general picture.

This empirico-statistical approach is the primary principle of all the research that we have conducted so far. When it becomes impossible to hold too great a volume of homogeneous information in one’s head, it needs to be processed with the application of statistical methods. In the present case this processing was minimal – it sufficed to collect and systematise all the names, their synonyms, the reports of wars, migrations etc.

The resulting picture is amazing from the viewpoint of Scaligerian history. One may get a more complete concept once one reads Part 6 of the present book.

It has to be said that individual fragments of the “unusual” picture that has revealed itself to us have been pointed out by different historians for a great many reasons. However, none of them appear to have considered this information as a whole. Moreover, the most “bizarre” mediaeval assertions that contradict Scaligerian history were usually ignored by the modern commentators and offhandedly declared to be “apparently erroneous”. We shall see many examples of such a tendentious attitude below.

As we have already pointed out, the entire table of geographical identification is given in Part 6 of the present book. We shall only cover the identity of the Sons of Japheth and the identity of the ancestors of the Scandinavian and European nations according to the Scandinavian sources.