Part 4.

Western European archaeology confirms our reconstruction, likewise mediaeval cartography and geography.

Chapter 13.

Surviving mediaeval geographical world maps do not contradict our reconstruction.

2. Conclusions made on the basis of the mediaeval maps.

2.1. Why the Great Wall of China doesn't figure on any maps predating 1617 in the "Art of Cartography" atlas.

The Great Wall of China is indicated on two Chinese maps dated by the chronologists as follows: the first one dates from 1155 A. D. or later, and the second, from the interval between 1311 and 1320 A. D. The maps are strictly local, and only depict the North of China. However, to the best of our estimation we could not find the year of compilation anywhere on the actual maps. Given all that we have learnt about Chinese history, it makes good sense to enquire: how is it known that the maps really date from the XII and the XIV century? We shall not conceal our opinion. It is likely that they were compiled in the XVII-XVIII century the earliest.

Now let us move on to the maps that were made in Europe. They instantly clarify the whole picture. See for yourselves.

The earliest European map to depict the Great Wall of China is map #31 from our list, which modern cartographers date to 1617, or the XVII century. Therefore, our reconstruction that claims the Great Wall of China to have been built in the XVII century and not any earlier is at the very least confirmed by the maps compiled in Europe and collected in the fundamental atlas ([1160]).

However, the fact that the first map whereupon we see the Great Wall really dates from 1617 is also far from self-implied. There are no chronological indications anywhere on the map. Therefore, we must ask the following justified question: who said that this map really dates from 1617 and not the end of the XVII century, for instance? After all, the rest of the European maps contained in the atlas ([1160]) that depict the Great Wall of China were manufactured in the second half of the XVII and in the XVIII century. They are numbered 47 (1666 or later), 34 (1675), 45 (1730) and 46 (1734).

2.2. Most ancient maps do not indicate the year of their compilation.

The above table demonstrates that out of 49 maps that we have processed, only six are marked by the date of their manufacture, one of which dates from the XV century (1442 A. D.), and the rest, already from the XVI century (1506, 1550 and 1587) and the XVIII century (1730 and 1734). All of these maps are fairly recent.

We remain in doubt about 24 of the maps, which either contain semi-obliterated lettering or indications written in a tiny script that cannot be read. The remaining 19 contain no chronological marks or references whatsoever. Thus, the majority of available maps dating from the XIV-XVII century shall have to be redated, since the facts that we encounter virtually everywhere seriously compromise the veracity of their datings.

2.3. Jerusalem as the primordial centre of the world. Indications of three cities (Jerusalem, Rome and Constantinople) appear on later maps.

According to our hypothesis, in the epoch of the XI-XVI century Troy, Jerusalem, New Rome, Czar-Grad and Constantinople were but different names of a single city on the Bosporus. Italian Rome did not exist in the XI-XIII century. It only became a noticeable city around the end of the XIV century.

The maps from the atlas ([1160]) do not contradict our hypothesis in the least, and confirm it in a number of cases. See for yourselves.

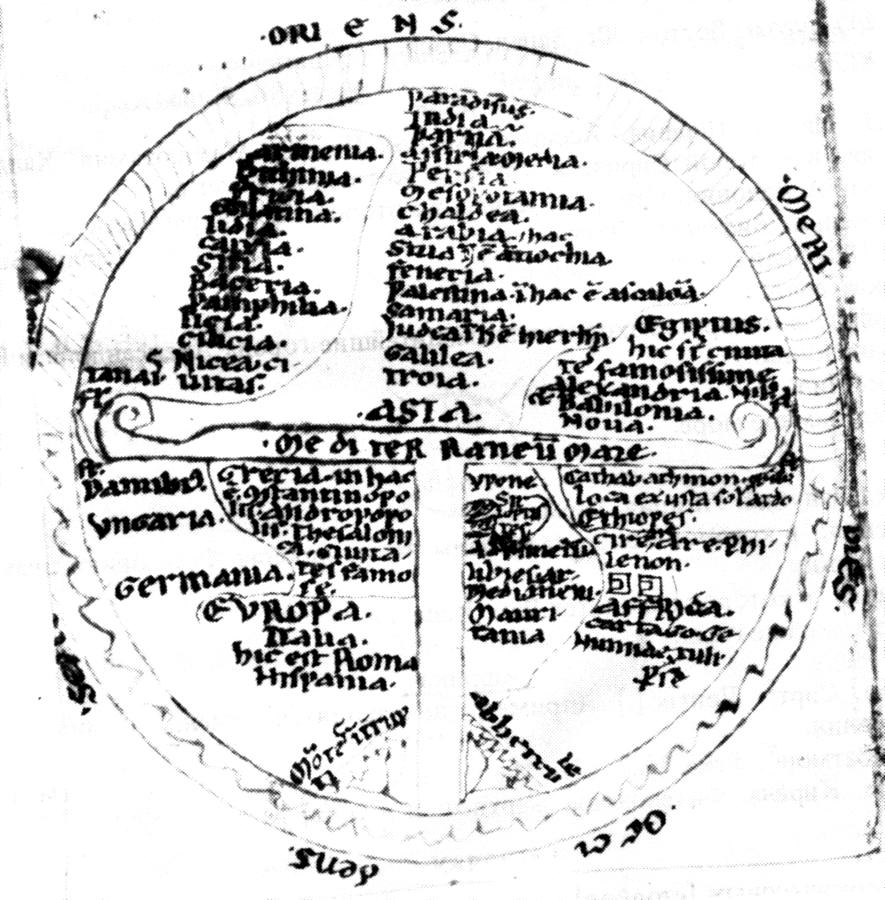

1) On an early map allegedly dating from 1276 (see #10 (2.3) in our table) we find Jerusalem at the centre of the world (fig. 13.2). Whether or not the map's dating is correct should be considered as a separate issue, which we shall not discuss presently. It is obvious that the author of the map considered Jerusalem the only capital of the world. In our reconstruction, the name of Jerusalem, the city of the Gospels, was still associated with Czar-Grad of New Rome in the XII-XVI century.

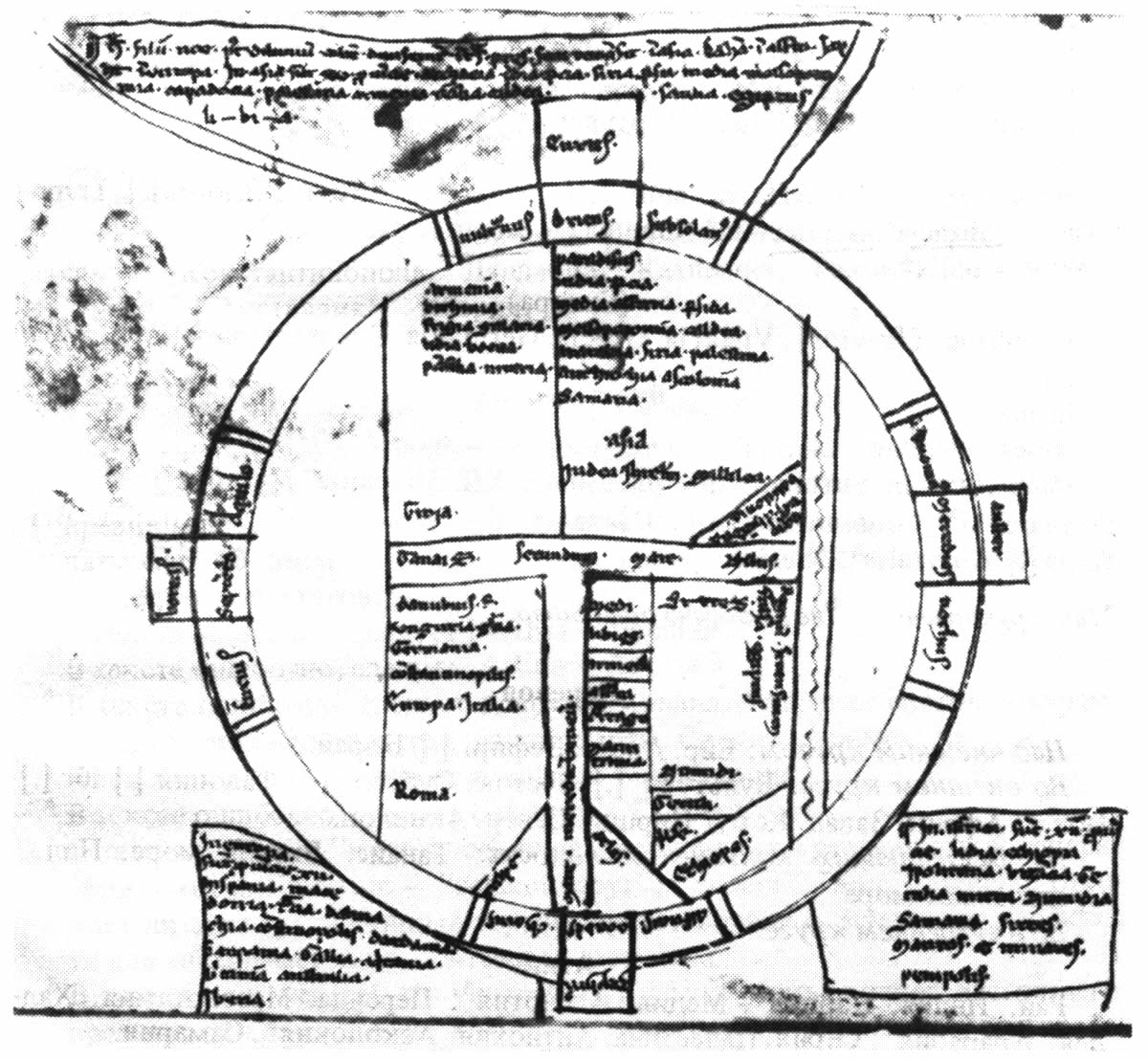

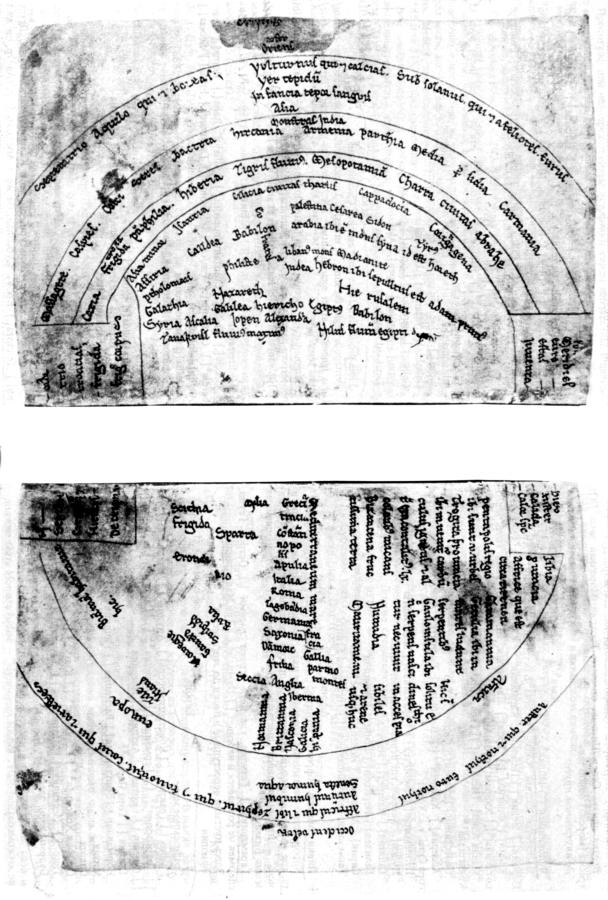

2) We see the same to be the case on map 11 (2.4), dated to the alleged XII century A. D. today (see fig. 8.1). Jerusalem stands at the very centre of the world as the primary capital (see fig. 13.3).

Apparently, ever since the epoch of the XII-XIII century and up until the XVI, Czar-Grad, or Jerusalem, was considered the centre of the world as known back then. This is how the maps depicted it. This leading role of Czar-Grad = Jerusalem = Troy is explained very easily. Christ (1152-1185) was crucified here in the XII century, so Jerusalem was the cradle of Christianity. It is obvious that the Evangelical Jerusalem = Constantinople should be considered the centre of the world for centuries to come.

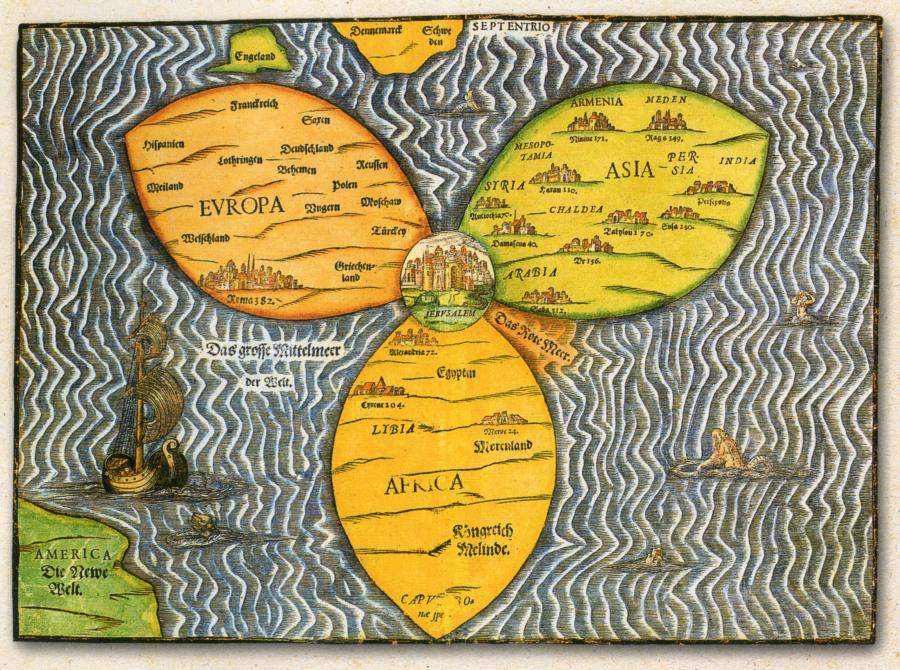

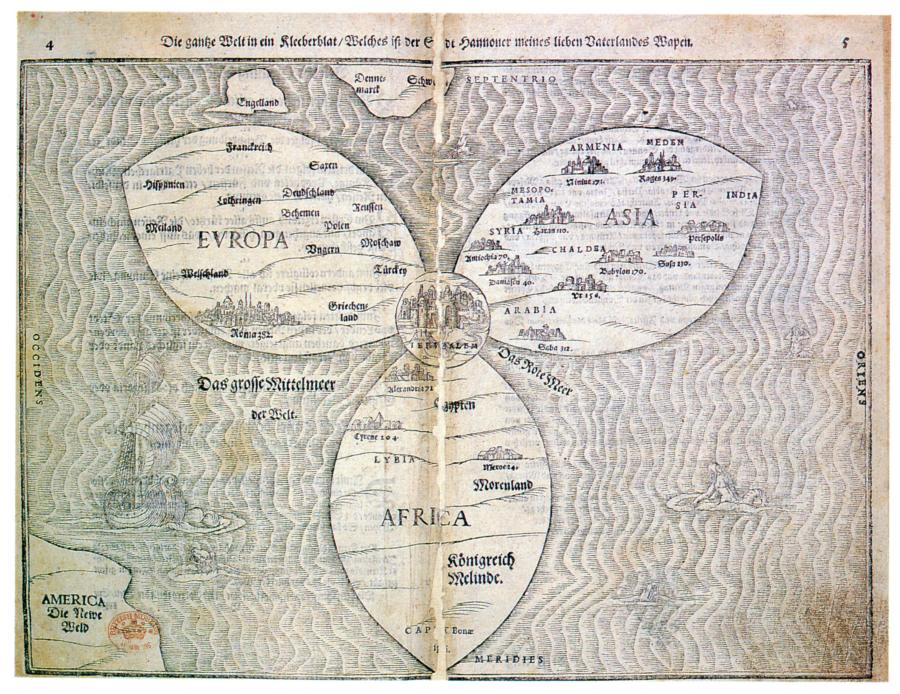

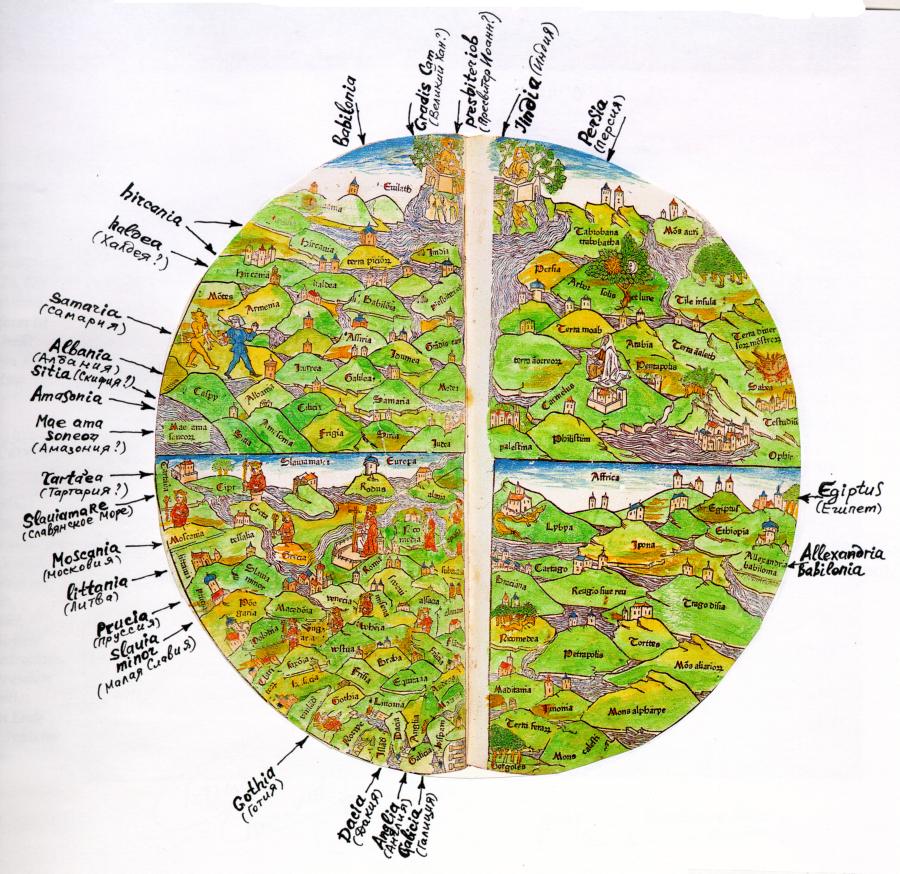

3) In figs. 13.4 and 13.5 we reproduce a world map that was presumably compiled in 1581. Jerusalem is placed at its very centre. It is drawn at the junction of the three continents, symbolically represented as three petals: Europe, Asia and Africa. The three petals obviously form a Christian cross whose centre is in Jerusalem. Such a representation of the Evangelical Jerusalem is in good correspondence with the location of Istanbul - the Bosporus Strait. Bear in mind that the Bosporus separates Europe from Asia. Africa lays further down south. It must be pointed out that although the authors of the map are already familiar with America, qv in the bottom left, the map in general is rather primitive. It must represent the low level of cartography as a science characteristic for the XVI century.

Let us remind the reader that many early maps of the XI-XVI century look like a circle with a T-shaped Christian cross in the centre (figs. 11.3, 11.4 and 11.5). The centre of the cross, where its two beams converge, was placed in the middle of the circular map, or the centre of the world. This is perfectly understandable - the Evangelical Jerusalem = Czar-Grad = Troy had stood here. This is where the XII-XVI century tradition of depicting the whole world as divided in three parts (Asia, Europe and Africa) must originate from, with a Christian cross at its hub - a representation of Jerusalem (see fig. 11.3). The XVI century map reproduced in figs. 13.4 and 13.5 is of the same type.

4) The map that was allegedly made in 1265 (see 5 (1.1) and (1.2) in our table) depicts nothing but Rome – no Jerusalem and no Constantinople (New Rome).

5) However, in the map that allegedly dates from 1339 (see 9 (2.1) and (2.5)) already shows three separate cities – Jerusalem at the centre of the world, Rome and Constantinople. The dating of this map needs to be verified – it is likely to be a lot newer than it is thought today.

According to our reconstruction, in the epoch of the XIV-XVI century the names Rome and Jerusalem started to multiply and spread all across the world map, becoming attached to different cities. Italian Rome, for instance, is likely to have appeared at the end of the XIV century. The name Jerusalem in modern Palestine must be of an even later origin – not earlier than the XVII-XVIII century. See more on this in CHRON6.

6) All the other maps from the Atlas [1160], whereupon Jerusalem, Rome and Constantinople are already depicted as three different cities date from the XV century the earliest. This fact is also in good correspondence with our reconstruction. In fig. 13.6 we see a circular world map of Lucas Brandis, allegedly compiled in 1475. According to the commentators, “the Earth is drawn cruciform, with the Orient at the top and Jerusalem at the centre” ([1160], page 38).

And so, initially the maps had depicted the Evangelical Jerusalem as the centre of the world; cartographers started to distinguish between Rome, Jerusalem and Constantinople as different cities several centuries later.

3. The evolution of the geographical descriptions and maps of the XI-XVI century. The condition they reached us in.

3.1. The reason for the multiplication of names on the maps of the XIV-XVI century.

According to our reconstruction, the Great = “Mongolian” Conquest, which had spread over enormous territories of Eurasia, resulted in the migration of the Russian and Turkic, as well as Ottoman = Ataman names of cities, rivers, areas etc in every which direction. The “Mongolian” conquerors came to the uncultivated lands and settled there, often using familiar names for referring to the new places in memory of their abandoned homeland. For instance, the name “Horde” became multiplied in this manner as it was brought to England, Spain and countless other regions of the Western Europe and Asia. The word Cossack also became duplicated, transforming into the names of a great many places separated from each other by thousands of kilometres (such as Spain and Japan, for instance, qv in CHRON4). The name “Russia” got multiplied as well – as P-Russia, or Prussia, Persia, Paris etc. The same happened to the names “Tartar” and “Turk”, which became Franks in the West and Turks in Asia, not to mention such names as Thracia, Africa etc. Actually, it is possible that the name “Turk” is a derivative of the Christian term “trinity” (“troitsa” in Russian), considering the frequent flexion of TS and K. The name “Troy” is yet another derivative.

Furthermore, the natural process of exporting names along the directions of the XIV-XV century conquest was complemented by another effect in the XVII-XVIII century, which has also led to additional duplications and the propagation of geographical names.

Let us remind the reader that one of the key results of our mathematical and statistical research as related in CHRON1 – CHRON3 was the discovery that the greater part of the ancient chronicles has a layered nature due to the fact that the final editions of these chronicles date from the XVII-XVIII century Basically, the original chronicles became covered by its duplicate, occasionally also with a chronological shift, which would create an elongated layered chronicle. The process could be repeated several times. This would result in the duplication of events, geographical shifts and altered dates.

A similar process has befallen geographical descriptions in the XVII-XVIII century. The research as described above leads us to a number of important corollaries, namely:

1) The first geographic descriptions weren’t scientific reports or maps as we understand them today, but rather brief lists of nations and lands. They were texts divided into several chapters, or countries.

2) The next phase involved circular maps divided into three sectors, namely, Europe, Asia and Africa. The three parts in question were Europe, Asia and Africa. They were divided from each other by the T-shaped Christian cross, qv in the previous section. The corresponding lands and peoples were listed inside each sector. This is the very shape of the ancient Scandinavian maps, for instance, attached to the geographical tractates, qv in figs. 11.3, 11.4 and 11.5.

fig.5.45, CHRON1

3) Later on, with the development of coastal navigation, came the maps with vague outlines of countries. The first seafarers drew seas as long rivers, unable to estimate the sizes of seas and oceans due to the lack of compasses – see the famous map of Hans Rüst dating from the alleged year 1480, for instance, which we reproduced in CHRON1, Chapter 5:11, fig. 5.45.

4) It is only much later that we find veracious shapes of the lands and the seas – namely, on the maps dating from the beginning of the epoch of Great Discoveries (the XV-XVI century), when the compass was already discovered. As we have already mentioned, in the epoch of the XIV-XVI century many geographical names became multiplied, brought by the Great = “Mongolian” conquerors to every part of the world that they colonised.

5) The creation and the implementation of Scaligerian chronology and the “new geography” dates from the XVII-XVIII century. Apparently, the analysis of this stage is particularly important in the reconstruction of the veracious picture of the past. The following is most likely to have happened.

Since the original geographical maps had a textual form and were in fact lists of names, they would inevitably become subject to the Scaligerian duplication effect, as we have demonstrated by the example of chronicles.

In the XVII-XVIII century Scaligerite historians started their process of wiping the Great = “Mongolian” Empire out of chronicle pages. In other words, a great many Imperial names have disappeared from the maps or moved elsewhere. Several geographical shifts, or re-localisations were made – for instance, the Evangelical Jerusalem is claimed to “have never existed” on Bosporus (and was “moved” in modern Palestina). Romanovian historians started to claim that the history of Novgorod the Great as described in chronicles was happening in the swampy and unpopulated marshes near the banks of River Volkhov and not on the Volga, in and around the famous Yaroslavl.

All the activity concerning the geographical relocations was carried out inside studies and amounts to paperwork and nothing else. Some famous “Mongolian” names were affixed to more or less “anonymous” parts of the Earth. Finally, the Imperial names transferred here were “attached” to the real nations populating these territories, becoming introduced into their conscience, geography and science, as well as passages from the ancient history of Russia, or the Horde, and the Ottoman = Ataman Empire, which were torn away from the old history and transplanted elsewhere; in other words, the events that occurred in Russia, for instance, ended up attached to provinces of the modern China.

Reformist missionaries armed with Scaligerian maps would arrive in Africa or China and tell the aboriginal population about the name of their land and their people in antiquity, as well as the glorious deeds of their ancestors. The locals would initially shrug in confusion, but later acknowledge these reports as veracious.

This is how the geographical names of many of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire’s provinces started to migrate in the XVII-XVIII century – first on paper, and later in reality. The process must have ended as late as in the XVIII-XIX century.

3.2. How the Imperial geographic names were transplanted to new soil in the XVII-XVIII century, accompanied by their historical descriptions.

Nations of the XVII-XVIII century that really resided in certain distant regions (the ones that became associated with the name “Mongolia” all of a sudden) already forgot the real meaning of this proud name. The idea of condensing the gigantic territory of the Great = “Mongolian” Empire to a puny spot on the border of the modern China was born in the faraway studies of the Reformist Europe as a result of geographic falsifications, errors and relocations.

However, the whole matter is that history and geography as known to us today were created by Scaligerite scientists in their studies. Having preserved the name “Mongolia” ascribing it to a small territory next to China, they went even further. Missionaries, travellers and scientists set forth in new directions defined by the maps, telling the locals that the ancient name of their land “has only just been discovered”, as well as the ancient history thereof described in such and such books. Just look at the multitude of maps – all these sources were found in European libraries recently. The locals’ ignorance was to blame for the lack of local records – however, the West European scientists would help them to restore their past, completely free of charge.

The locals were told that they really committed great deeds in antiquity, and so they were not to worry and not to object; the best thing that could be advised to the locals was to look for some remnants of their past, preferably ruins, sepulchres and so forth. Fitting ones - remnants of a foundation, fragments of statues, a few gutters = Babylon, a city destroyed many centuries ago. This means, however, virtually nothing has remained of it, but nevertheless – we know how great a city it once was from books found in Europe recently.

A given place could be identified as the residence of the legendary King Nimrod, and another hill – as the location of the Persian King Cyrus’s headquarters during the storm of Babylon – the books clearly state that he was “standing on a hill”, and the hill surely looks fitting, especially if there are ancient stones here to this date. Cyrus must have leaned against one of them, and it would be of great interest to find out which one.

Any opponents (old sages etc) telling that neither they, nor their ancestors knew of any such events, were declared pagan shamans and evil sorcerers – enemies of civilization and the religious mission of the holy fathers, who had fire as the ultimate means of converting the non-believers.

Needless to say, the locals sat around fires and listened to the tales of the missionaries with great interest. First they must have expressed disbelief, then started to express their agreement and finally passionately sought for proof – and doubtlessly found it. Jugs, decorations, ruins of some sort, which could be interpreted in any which way. Nobody expected the grey stones to be inscribed with “here be Homer’s Troy destroyed in the XIII century B. C.”.

Then come other scientists and poll the aborigines. This results in voluminous archaeological reports about “the discovery of doubtless confirmations of historical sources on site”. The locals eventually started to feel great pride at the sight of the rich tourists who arrive to their village in throngs in order to take a look at the “remnants of the ancient capital” Its inhabitants recollect their former glory with great solemnity and austerity, surrounded by exalted connoisseurs of ancient artefacts. Cyrus, King of Persia, leaned against the stone on the left. There’s still a print of his hand on the stone.

Everyone is satisfied.

To voice criticisms of this viewpoint today means to provoke:

1) true rage of many historians and archaeologists, whose predecessors were responsible for many forgeries, miscalculations and errors;

2) authentic outrage among the locals, who have become accustomed to the flattering and lucrative legend;

3) real fury of tourist companies who make a good living from the demonstration of “authentic remnants of an ancient civilisation”,

4) a great grudge for the gullible tourists, who have touched the “holy relics of the ancient statues” in a pious and solemn way.

All of them will cry out: “So many people couldn’t have been so wrong for so long!”

We shall refrain from arguing – let us only remind about the fact that people had once honestly believed the Earth to be a flat disc carried by four elephants, and also that the Sun rotated around the Earth. History of science knows many examples of consensual errors.

Scaligerian history and geography are but arbitrary constructs implanted into human consciousness.

3.3. Tedious descriptive diaries of actual voyages and thrilling tales written in comfortable studies.

Apart from the process that involved deliberate obliteration of records concerning the Great = “Mongolian” Empire, there was another, of a literary character; it concerned the geographical descriptions, so popular in the XVIII-XIX century. Of course, there were actual voyage records among them – most likely, brief and confused, an arduous and tedious read.

However, some of them were bearing distinct marks of academic style – for instance, works of Roman publishers and commentators written in the XVII-XVIII century as extensive literary works based on collected brief notes of real travellers. These works were doubtlessly useful and important, yet of a cabinet nature. Apart from genuine virtues, they also had some important vices.

For instance, let us consider a real Venetian traveller of the XIV-XVI century who visited Russia, or the Horde, and described it as a faraway land in Asia (India in Asia, in other words). A while later, the brief original text of his notes ends up in the study of a European scientist (operating from Rome, for instance) who collects information about remote countries and treats the ancient documents with the utmost respect.

Yet the Roman scientist of the XVII-XVIII century lived in the epoch when the name India became firmly associated with its modern equivalent, whereas the old meaning (“faraway land”) became thoroughly forgotten. Seeing a reference to India in Asia, such a scientist would assume that he was confronted with one of the first ancient descriptions referring to voyages to India in its modern meaning.

The Roman writer of the XVII-XVIII century would complement the old and brief account of his Venetian predecessor of the XIV-XVI century with new and authentic data concerning the wondrous land of India, where elephants and apes roam free and many amazing things happen.

In order to make the account more interesting for his contemporaries, this author might add something about people with one foot, the Phoenix Bird etc, as though he really saw them and nearly perished in the jaws of a gigantic bear-headed crocodile.

We get a Jules Verne story as a result. The author in question never travelled anywhere, didn’t submerge on the “Nautilus” or die in the clutches of an enormous kraken – he sat in a quiet study, read encyclopaedias and notes of real travellers and wrote fascinating novels swept off the shelves of bookshops by adoring multitudes of readers.

One must think that the genre of fascinating geographical novels was just as popular in the XVII-XVIII century. People have always been interested in mysterious distant lands. And a vicarious experience is always more easily affordable than a real journey – it is enough to recollect one’s love of Jules Verne from the childhood.

Thus, the Roman of the XVII-XVIII century created something similar to the geographical novel of Verne basing it on real notes left by his Venetian predecessor of the XIV-XVI century.

Time goes by, and the vicarious “Roman account” begins a life of its very own. Finally, it ends up in the study of a German scientist, a historian of the XVIII-XIX century who collects mediaeval information about faraway countries. He also treats the Roman “Journey to India” with the utmost respect and interest. What does he learn from the “mediaeval traveller”?

The German scientist rejects the tales of dragons and monster whales that swallow whole fleets of ships – one no longer believed in such things in the XVIII or the XIX century. However, the rest was trusted completely, and served as the basis for a “scientific reconstruction” of the journey in question.

This scientist would instantly come to the conclusion that the traveller visited India in its modern localisation, given the references to elephants, monkeys, parrots, crocodiles etc.

However, this conclusion would be erroneous, since the actual Venetian traveller had really visited the ancient Russia – a “faraway land”, or “India”, in other words. All the details of the modern Indian entourage were added by one of Jules Verne’s colleagues in the XVII-XVIII century.

We have been confronted by the layered chronicle effect – the first layer is authentic and brief, and concerns a voyage to the ancient Russia, or the Horde – a “distant land”, or “India” The second layer is more detailed but literary, and consists of a late description of India in its modern meaning.

Our opponents might counter with the notion that the above scheme reflects nothing but our theoretical constructs. How about actual examples of such layered geographic descriptions of voyages?

They do exist, and we shall be considering them in the next chapter. It was for a good reason that we chose a certain famous Venetian traveller as an example.