Part 4.

Western European archaeology confirms our reconstruction, likewise mediaeval cartography and geography.

Chapter 14.

The real contents of Marco Polo's famous book.

14. The itinerary of Marco Polo.

“Marco Polo, during the period of his

administrative activity in China, has

studied the countries that comprise

Kublah’s Empire so thoroughly and

describes them in such great detail

that one needs to conduct a great deal

of preliminary research in order to

comprehend the account of the great

Venetian”.

From the preface to [416] by N. Veselovskiy.

14.1. Futile attempts of the commentators to retrace the itinerary of Marco Polo.

We shall cite a number of passages from the book entitled “The comments of Archimandrite Palladiy Kafarov to the voyage of Marco Polo through northern China” ([416]). Let us recollect that Archimandrite Palladiy (Kafarov) is a famous Christian missionary of the XIX century who had spent a long time in China.

He writes: “In the comments related below I mean to verify certain evidence given by Marco Polo about his arrival in China . . . with the aid of Chinese documents . . .

Charchan. No such name can be found in either the XIV century map or any other surviving document of the Mongolian nation . . .

Lop, etc. Neither Chinese history or geography mention the existence of a city called Lob near a lake named similarly . . .

Shachiu. Sha Chow . . . has always been considered a very important location . . . Marco Polo does not mention a certain trait of Sha Chow, a sandy hill . . . or a hill of “rumbling sand”: the sand slides down the slope of the hill and makes a special noise that resembles the sound of distant thunder . . .

This fact, namely, the existence of a road from Ichin to Kharakhorum must have given Marco Polo a reason for taking a trip (a vicarious one, I believe) into the steppes of the Mongolian Khans’ Horde . . .

Calachan, or the capital of the Yerighai region; Marco Polo continues to isolate the Tangut Kingdom and refers to phenomena that already had not existed by his time, yet stayed alive in folk memory” ([416], pages 5, 6, 8, 13-14 and 22).

And so on, and so forth.

It is known that Marco Polo’s book contains a description of several journeys. It is traditionally assumed that they all took place in different places and spanned territories from Italy to the South-East Asia, including India, China and Indochina. Traditional attempts of reconstructing the true geography of Marco Polo’s travels can hardly be called successful. See for yourselves.

In order to make Polo’s reports correspond to the modern map in any way at all, the commentators are forced to make the following geographical re-identifications ([1071], pages 108-109):

1) Central India was moved to Africa (!) – near the source of the Nile, no less.

2) The Great Turkey was relocated into the region of Lake Baikal.

3) They refer to the entire Siberia as to “Dominion Conehi”.

4) River Volga becomes Tigris ([1078], map after page 144).

Well aware of the problems arising from the parallels drawn between Marco Polo’s descriptions and modern, or de facto Scaligerian geography, historians often say that “Marco Polo . . . refers to lands that he heard about, but never visited, as to islands” ([473], page 245).

Our reconstruction implies an altogether different and a great deal more trustworthy picture of Polo’s journey. Apparently, he never travelled any further than the Ural, and therefore he never visited China or India (or the territories known as such today), let alone the modern islands of Java and Sumatra.

His book does indeed contain reports pertaining to several journeys – maybe made by a number of characters, which is what the commentators appear to imply, saying that the very first voyages were made by Polo the senior. As a result, the same locations, and primarily Russia, or the Horde, became described several times.

The journey would begin from Constantinople. The first volume of [1264] contains a part of Polo’s book that describes Tartary primarily. He tells us about Genghis-Khan, his struggle against Presbyter Johannes and the customs of the Great Khan’s court. We have already mentioned all of the above, so let us merely make a small number of additional remarks.

14.2. The location of Karakorum, or the Great Khan’s capital.

Due to their incorrect perception of Polo’s voyage, commentators locate Karakorum, or the Great Khan’s capital, in the area to the south of Baikal in Siberia. We hardly need to remind the reader that the archaeologists are still searching for this city here, but to no avail, qv in CHRON4, Introduction:2. Nevertheless, as we have already mentioned, one must recollect the city of Semikarakorsk in the lower Don, not far away from the Crimea. This leads us to the hypothesis that “Karakorum” translates as “black Crimea”, since “Kara” is the Turkic for “black”, whereas “korum” must stand for Crimea (see [831], page 128).

Furthermore, Karakorum, the “Tartar” capital, was formerly known as Kara Balgasun ([1264], Volume 1, pages 228-230). This name probably means “black Volga” or “Black Bulgaria”. Therefore, the very name of the “Tartar” capital is a reference to Don or the Volga, and not Central Siberia. Apparently, Balge-Su(v) translates along the lines of “River Volga”, since the Turkic “Su” or “Suv” does in fact stand for “river” or “water”.

This is in good correspondence with our reconstruction, according to which Marco Polo, who visited the headquarters of the Great Khan in Yaroslavl, or Novgorod, in the epoch of the XIV-XVI century must indeed have travelled up the Volga, possibly, visiting Crimea prior to that.

Actually, modern historians when they reconstruct the itinerary of Marco Polo (qv in [673]) believe that he had covered the distance between the Black Sea and the Volga Bulgars, and only after that they trace it towards Mongolia – Polo needed to reach the capital of the Great Khan, after all ([673], page 21).

14.3. Cossacks on the pages of Marco Polo’s book as the Great Khan’s guard.

Polo reports that “in order to maintain order in his empire, the Great Khan used his guard of twelve thousand horsemen known as Cossacks (“Keshican”, qv in [1264], Volume 1, page 379). Thus, the Cossacks are named explicitly. Further on, Polo describes how the military force of the Cossacks is organised. Incidentally, in some manuscripts of Polo’s book we find the word “Casitan” here ([1264], Volume 1, page 379, comment 1). That is, Kaz + Tan, or, possibly, “Don Cossacks”, which makes our suspicions even stronger.

14.4. The Black Sea.

Polo mentions “the great River Caramoran . . . it is so great that no bridge can be thrown across it, since its width and depth are great, and it even reaches the Great Ocean which surrounds the Universe. There are many settlements and fortified cities of stone there, and it is visited by many traders” ([1264], Volume 2, page 22).

The actual name of the “river”, which is “Kara-Moran”, is doubtlessly referring to the Black Sea (“Kara” = “black”, “moran” = “sea”). We needn’t be confused by the fact that Polo called a sea “river”. In the Middle Ages, the epoch of coastal trade, seas were often called rivers, and reproduced upon maps as such – for example, they are drawn as narrow rivers in [1160] and [1177]; see also CHRON5, Chapter 13:3.1.

Modern commentators also note that Polo calls Red Sea river ([1078], page 93). The description of the “Chinese river” Caramoran that we find in Marco Polo’s book corresponds to the characteristics of Black Sea.

14.5. The country of Mongolia.

Leaving Caramoran, or the Black Sea behind, Polo comes to the city of Mangalai, the Great Khan’s son ([1264], Volume 2, page 24). The city is surrounded by sturdy walls, five miles long. There is a large market inside the city, where there are many goldsmiths, as well as other craftsmen.

Our reconstruction explains everything perfectly – Polo comes to Mongolia, or the Great Kingdom = Russia, or the Horde.

14.6. Amazonia.

As he moved further, Polo ended up in the country of Manzi ([1264], Volume 2, page 33). This is where we find the Azov sea, to the north of Black Sea, and the land of the Amazons was just there (see Orbini’s book, for instance; also CHRON4, Chapter 4:6). The land of the Amazons was called “Manzi” by Polo – the original name is easily recognizable.

Let us also recollect the ethnic group of Mansi, known well in Russian history – they lived on the Middle Volga ([952]). Once again, perfect correspondence with Polo’s “Manzi” as well as our reconstruction.

Polo returns to the Amazons once more when he describes the land of Scotra, or Scotia (Scythia). See more in re Scythia = Scotia and the Amazons in Part 6. Polo writes about the existence of “two islands” in those parts, or two “Asian lands”, as we have explained already, “one female and one male” ([1264], Volume 2, page 404). The husbands inhabit one of the “islands”, and the wives, the other; they only meet for three months each year – between March and May.

It is curious that the amazons are described in similar terms in the Russian “Povest Vremennyth Let” ([716], page 15). They are even named similarly to Polo’s version – “Masonians”, qv in [716], page 15. Let us quote this passage according to [715]: “And the Masonian [in other manuscripts “Mazon” and “Amazon”] women have no husband . . . but one spring day they leave their land and mate with men from neighbouring countries. Those who give birth to boys have to destroy their offspring, whereas the ones who bear girls raise them with great care” (quoted according to [715], Volume 2, page 22; see also [716], page 15.

14.7. The great market and the customs office in the Russian city of Azov.

Next Polo comes to a large city where he sees an enormous market and a customs office that collects taxes and fees ([1264], Volume 1, page 36-37). The city is called Thindafu (in some manuscripts – Sindu), qv in [1264], Volume 2, page 37, comment 1. If we disregard the standard suffix “fu”, which must have been added in a later edition to make Polo’s book more “Chinese”, we see the city of Tind or Tana.

However, Tana is one of the famous mediaeval names of Azov, a city in Russia ([1078], page 140). It stands on the Azov Sea, right next to the Don (Tan, or Tanais). Moreover, commentators themselves tell us that “in the XIV century . . . the overland trade between Italy and China went through Tana (or Azov), also through Astrakhan” ([1078], page 140). Thus, Marco Polo followed the general trade route between Italy and Russia, finally arriving in Azov.

According to the modern commentators of Polo’s book, all of the above took place on the territory of the modern China. This is erroneous.

14.8. Polo’s further itinerary.

In the description of Marco Polo’s voyage to India we see that he had “visited the place where the holy remnants of St. Thomas the apostle were kept” ([673], page 188). St. Thomas is known to have read his sermons in India: “Indian Christians have long called themselves ‘Christians of St. Thomas’, and they trace the history of their church back to this apostle. Thomas died in the city of Malipur” ([936], Volume 3, page 131). This might be the famous city of Mariupol on the shores of the Azov Sea. One of the oldest and largest burial mounds in Europe was found in Mariupol ([85], Volume 26, page 288). Then the city of Edessa mentioned nearby is most likely to identify as Odessa or some ancient settlement in its vicinity. “The holy relics of St. Thomas the Apostle were taken to the city of Edessa in the year of 385 A. D.” ([936], Volume 3, page 131).

Doesn’t the above imply that Marco Polo paid a visit to Odessa during his journey through India, or “a faraway land”?

We shall refrain from making our narrative even more cumbersome by further details of Marco Polo’s voyage. His test is genuinely old, the names were translated from one language to another several times, and have also undergone several editions. Polo’s descriptions are very general and often built according to the same scheme: a great king (or several great kings), an abundance of gold, idol-worshippers and the subjects of the Great Khan.

Marco Polo appears to have travelled in the area of the Volga for a long time; he may have visited the source of River Kama. The salt mines that impressed him so greatly must have been located in those parts – the old Russian city of Solikamsk still stands here.

It is possible that Marco Polo’s Sumatra and Java derive from the names of the Russian rivers Samara and Yaiva in Middle Volga. The city of Samara stands on the river of the same name; we have already mentioned it, as well as its connexion with Marco Polo’s name. The names reflect that of Sarmatia, another alias of Scythia, or Russia.

The Russian River Yaiva is also located here – it is a tributary of Kama, and its name has never been changed ([952], pages 15 and 61). Marco Polo could indeed have visited these parts, since an ancient trade route passed through these parts, as well as an ancient Russian road known as Cherdynskaya ([952], page 16), two thousand verst long. Hence the likelihood of Marco Polo’s travels through these localities. Then the Scaligerian paper migration of Russian names to South-Eastern Asia transformed these names into “the two isles – Java and Sumatra”.

Apart from other things, Marco Polo declares: “Their money is golden; they use pig-shells [?! – Auth.] as small change” ([1264], Volume 2, page 85).

Polo or his later translators must have become confused here. They were clearly unaware that the word used for referring to a pig’s snout and a five-kopek coin is the same in the Russian language – namely, “pyatak”; this is how a small Russian coin transformed into a mysterious “pig-shell” in one of the translations.

The legendary Rukh Bird is referred to as “Ruc” by Marco Polo – Russian bird, no less ([1264], Volume 2, page 412). This is hardly surprising, seeing as how the graphical representations of a large bird are indeed found in Russian architecture quite often – in churches particularly. An interesting picture of the Rukh Bird, which is based on an ancient Arabic drawing, is reproduced in fig. 14.27.

Finally, Polo appears to have headed Westward via Western Ukraine, Poland, Germany and France.

He calls Western Ukraine “Great Turkey”, making a reference to the haiduks (or “Caidu”), adding that there is never any peace between King Caidu and the Great Khan, his uncle. The two constantly wage war against each other, and there were many large battles fought between the armies of the Great Khan and King Caidu. The original dispute between the two began when Caidu demanded a share of his father’s conquest loot from the Great Khan – parts of the Cathay and Manzi regions ([1264], Volume 2, page 457).

The Great Khan refused to satisfy Caidu’s request, and the two rulers’ armies started to engage in skirmishes: “Still Caidu [the haiduk – Auth.] raided the Great Khan’s lands . . . He has many princes near him whose bloodline is imperial, or Genghis-Khan’s” ([673], page 212). The Great Khan’s son and the grandson of Presbyter Johannes fights against Caidu. Let us consider the description of one such battle: “They grabbed their bows and started to shoot at one another. The arrows filled the air like rain . . . When all the arrows came out, they put their bows back into their quivers and grabbed their swords and maces as the two armies engaged in hand-to-hand combat” ([673], page 213).

Polo continues: “Nevertheless, King Caidu shall never assault the lands of the Great Khan, forever remaining a menace to his enemies” ([1264], Volume 2, pages 458-459).

The readers must have realised it a long time ago that Polo could have been describing the relations between Russia and West Ukraine (or Poland) - a well-known scenario of frequent disputes. However, they cannot predate the XVI-XVII century, which is when the Great Empire fell apart. No such thing could have happened in the “Mongolian” times of the Ottomans, or the Atamans.

Actually, Polo provides a correct localisation of the Great Turkey as Ukraine, which lays to the Northwest of Hormos ([1264], Volume 2, page 458). Modern commentators are completely incorrect to insist on contradicting Polo’s text and indicating the location of Polo’s “Great Turkey” in far Siberia ([1078, pages 108-109) or Turkistan ([673]).

Polo also mentions a nephew of Prince Haidu, simply calling him suzerain (Yesudar, which is almost identical to “Gosudar” – the Russian for “ruler”). See [1264], Volume 2, page 459). He also mentions that all of them are Christians.

It is possible that Marco Polo’s book also includes the descriptions of Lombardy and France as “Lambri” and “Fansur” ([1264], Volume 2, page 299).

Finally, let us comment the constant references to the alleged idolatry of all these characters as made by Marco Polo. Some might actually think that such words can only apply to savages and the primitive worship of idols somewhere in the insular part of the South-East Asia.

We must disappoint the reader. The word “idolatry” was frequently used in mediaeval religious disputes. It is often mentioned in the Bible as well. This is what the mediaeval traveller, Brother Jourdan from the Order of Confessors is telling us in the alleged XIV century:

“I can only tell what I have heard from people about Great Tartary . . . This empire has temples with idols, as well as male and female monasteries that resemble ours, and they observe fasts and pray there just like we do; the head priests of these idols wear crimson attire and hats, just like our cardinals. It is amazing just how splendid and grandiose their idolatry really is” ([677], page 99).

Therefore, the West Europeans referred to the Orthodox Christians as “idol-worshippers” – it would be expedient to compare these data to the account of S. Herberstein, who wrote about Russia in the alleged XVI century A. D. ([161]).

“To the East and the South of River Mosha . . . we find the people of Mordva, who have a language of their own and obey the Muscovite king. Some call them Mohammedans, others, idol-worshippers” ([161], page 134). Carrying on with his description of the Muscovite kingdom, Herberstein writes the following, presumably referring to some Russian guidebook ([161], page 160): “Many black people come from the region of this lake” ([161], page 157). Herberstein writes about some Chinese lake that he believes to be at the source of River Ob. It is important that Herberstein writes about these things while sitting in Moscow, without any attempts of concealing it. He honestly tells the reader that these fable-like things were translated to him from a guidebook of some sort (pages 157 and 160). Had he been less sceptical about it, wishing to pass for an eyewitness, we would get a text resembling the edited Marco Polo. In general, could Herberstein’s book of the alleged XVI century have served as one of the originals of Marco Polo’s book?

15. After Marco Polo.

It would be curious to compare the book of Marco Polo to the writings of European travellers who visited the modern India in the alleged XIV century (as we understand today – in the XVI-XVII or even the XVIII century – see [677]). There were few of them, but they already describe the South-East Asia correctly, with specific details that give us no reason to doubt the real identity of these lands. In the XVII-VIII century, already after Marco Polo, the West Europeans finally found a route to the South-East Asia.

This is how the transfer of Marco Polo’s geography (including that of “India”) began in the minds of the Westerners – they started their “discovery of the lost India” in the South-Eastern Asia. Why did they lose it, and when did it happen?

Our reconstruction answers the question perfectly well. “India” was lost by the Western Europe during the epoch of the religious schism, or the XVI century. Having severed relations with the Orthodox Christians and the Muslim, the Roman Catholic Europeans de facto lost their former route to the Orient – Russia, or the Horde, and the Ottomans (Atamans) simply denied them the right of passage.

This is when “India”, or the Horde, started to transform into a fable-like land for the West Europeans, becoming ever more legendary. The fantasy version was made more or less uniform in later editions of Marco Polo’s book – the ones that have reached our day.

It is obvious that the West Europeans started to search for a new way to the East – towards the spices, silks etc, which still reached them through the Russian markets, but for exorbitant prices. This is how the epoch of the Great Discoveries began – we all know that the seafarers of the Western Europe were looking for India – the land of spices, gold and diamonds.

As we already mentioned, the seafarers took Marco Polo’s book along with them, and, landing on the shores of faraway countries and islands that they discovered, they named them in accordance with Marco Polo’s book, failing to realise that Marco Polo has never been anywhere near those parts. Even if they did realise this, they must have been chasing the dangerous thought away from themselves – otherwise they would have to sail further in order to find the evasive India, and they were already mortally tired, wanting nothing more than reporting victory to their king . . .

16. Summary.

This is how the “lost India and China of Marco Polo” were rediscovered. The names were naturally of little importance. The Europeans found what they wanted most – sources of silk and spices. Their only mistake was that they were certain that the old names India and China as written in Marco Polo’s book have always referred to the exotic lands that they have discovered and euphorically dubbed thus, simultaneously suppressing the association between these names and Russia, or the Horde.

This actual error was generally harmless – multiplying geographical names on the map and not much else. However, the implication was a great deal less harmless, since, according to Marco Polo, the court of the Great Khan, the famous “Mongolian” conqueror, became relocated to China. Now, Marco Polo’s book used this name for referring to the Horde, or Russia; when it travelled to the Far East in the XVII century, this is where the centre of the “Mongolian” conquest has moved. Archaeologists started their diligent search of the Great = “Mongolian” capital of the world, or Karakorum, in the Far East, which was a serious mistake.

17. Addendum. Alaskan History.

We shall be quoting additional books here ([al1] – [al4]), which weren’t indicated in the main bibliography to the seven volumes, and are listed at the end of the present section.

Let us begin with relating the consensual version of Alaskan history. It is believed to be as follows. Presumably, up until the XVII or even the XVIII century, Alaska was inhabited by the indigenous tribes of Indians and Eskimos, whose lifestyle was primitive and savage-like. Historians believe that civilisation only reached Alaska in the XVIII century. The discovery of the Bering Strait and Alaska is associated with the names of Bering, Cook and other seafarers of the XVIII century. However, according to other sources, this strait was discovered by the Cossack Semyon Dezhnev in 1648: “The proof that America doesn’t connect with Asia was given by the Cossack Dezhnev in 1648 – he was the discoverer of the Bering Strait, visited by Bering in 1725-1728 and named accordingly” ([al1], Volume 2, page 637). But, as we are told, Russians only came to Alaska after Bering. If we’re to believe the Great Soviet Encyclopaedia, “in 1784, Shelekhov founded the first Russian settlement on Isle Kodyak; Russian settlements in the nearby parts of the American continent started to appear in 1786” ([85], Volume 2, page 205).

The colonisation of Alaska was started by a trade company founded in 1798 in St. Petersburg for this actual purpose ([797], page 1232) that became known as the Russian-American Company [85], Volume 2, page 205). In 1799, the Company “received the exclusive right of monopoly over the use of the former Russian discoveries in the North Pacific, as well as further discoveries, trade and colonisation of lands unclaimed by the other nations, starting with the 55th degree of Northern Latitude on the American continent unto the Bering Strait and beyond, and also on the Aleutian, Kurilian and other islands” ([85], Volume 2, page 205).

We must instantly note that all the “first colonisation” dates fall in the range of the first few years after the defeat of Pougachev in 1774.

It is interesting that the Russian capital of Alaska, or Novoarkhangelsk, was founded in 1784 near the “former fortification on Isle Sitka, which was destroyed by the Tlinkit Indians in 1802” ([85], Volume 2, page 205). We must be hearing the echoes of the wars in Alaska, which rolled over the former land of the Horde after the defeat of Pougachev by the Romanovs. According to our reconstruction, Alaska had formerly belonged to Muscovite Tartary, which was defeated in 1774. After that, the conquest of this country’s vast territories started – up until the very North of the American continent, Alaska in particular. Obviously, the Romanovian invasion here was of a military nature. It is likely that the consensual version of history represents the battles against the last remnants of the Horde, or “Mongolia”, as skirmishes with “Tlinkit Indians”. Incidentally, aren’t we hearing a repercussion of the name “Kitai”, or Scythia, in their name?

“In 1812, the fortification of Ross was created . . . on the coast of North California . . . as a base for Russian seamen and entrepreneurs” ([85], Volume 2, page 205). However, the Romanovian Russian-American Company didn’t venture any further in its conquest of America, since another Company instantly expressed an interest in the lands that instantly became “free for colonisation”, created by the nascent United States of America, which were made an independent state in 1776 during the “War of Independence” fought in 1775-1783, qv in [797], page 1232 – this war started immediately after the victory of the Romanovs over Pougachev. See CHRON4, Chapter 12, for more details.

Basically, a struggle over the vast territories of the Horde started between the Romanovs and the newborn USA. The Romanovs were approaching from the East, and the USA, from the West. They must have run into each other at some point – it is possible that there was military action between the two. Modern history is silent about this. The local populace must have inevitably been involved in military action – after all, they lived upon the land for several centuries on end. However, the Russians were caught between the hammer and the anvil here. Nevertheless, they provided resistance for a long enough time.

A very interesting question about Alaska concerns the time and the circumstances of its sale, as well as whether it was “sold” in the first place. There are different versions voiced on this matter. The most popular point of view today concerns the fact that Alaska was either sold, or rented out to the USA by the Romanovs in 1867 for a preposterously small amount of money. Modern encyclopaedias have been using the term “sold” ever since the second half of the XX century ([797], page 47; also [a2], Volume 2, page 206). However, earlier sources, such as the 1890 edition of the “Encyclopaedic Dictionary” of Brockhaus and Ephron, for instance, as well as the “Concise Soviet Encyclopaedia” of 1928, are using the term “ceded for severance”. We quote: “These territories . . . are made up from former Russian territories in America, which were ceded to the United States of North America for a severance of 7.200.000 dollars according to the agreement signed in Washington on 30 March 1867 and ratified by the Senate on 28 May” ([al1], Volume 2, page 598). As for the “Concise Soviet Dictionary”, it tells us “Alaska was handed to the United States for a severance of 14.320.000 roubles” ([al4], page 248).

The term “sale” wasn’t used until much later, in other words. The sources that date from the epoch of this event tell us the territory in question was “ceded for a severance”. This term must be reflecting the matter with much greater exactitude – it is in perfect correspondence with our idea that none of this land had originally belonged to Russia or the USA and couldn’t be sold by one party to the other for this very reason. These lands could only be ceded by one party to the other in a territorial dispute over the lands that belonged to neither party. The Romanovs must have realised finally that they would not be able to hold Alaska, and demanded a severance fee as a reward for their withdrawal from America. The offer was taken. The price suited the Romanovs, even though it had equalled a mere 7 million dollars. As we realise, this price would be preposterous if we are to understand it as the cost of a whole country with its endless resources – gold, silver, oil, coal, copper, lead etc ([al4], Volume 4, page 250). Even the land itself, being an enormous territory, cost more than the sum in question. However, if we’re to regard it as a “severance fee”, or compensation for withdrawal from a land that could not be taken by force, everything becomes perfectly clear. The Romanovs were happy with as little – it was better than nothing, after all.

Our opponents might counter that the action in question wasn’t really the annexation of another country, but rather the colonization of an “uninhabited territory”. However, later events are difficult to associate with such a viewpoint. Namely, it turns out “the territorial government of the USA, founded in Alaska in 1869, didn’t exist for too long due to the paucity of the country’s white population – a governmental apparatus of this size turned out quite extraneous, and the united government entrusted all of its Alaskan affairs to the captain of one of the ships anchored at the shore” ([al1], Volume 2, page 598). Moreover, before 1884 Alaskan matters “were taken care of by the American Ministry of Defence” ([797], page 47).

These facts correspond to the reality of pacifying unquiet territories of the Horde, but hardly to the colonization of deserted lands populated by a handful of savages – armed with nothing but bows and spears, as we are told today. Why would the military governor of Alaska have to hide away on a ship, ready to hoist away every second and flee for his very life? Afraid of pirogues and tiny kayaks? The captain of an American battleship, armed with heavy cannons?

Up until this very day there is a large indigenous population in the Alaska, which still speaks Russian. Could they be the offspring of the Russian-American Campaign’s individual expeditions for over half a century? After all, in order to keep a language alive for some centuries, one needs more than three or four hundred people – tens of thousands at least, and firm roots.

The American state of Oregon appears to be yet another piece of Muscovite Tartary in America – it only became part of the USA in 1859 ([1447], page 627). Some of its indigenous populace had spoken Russian up until very recently. Incidentally, there was some struggle about Oregon as well during the same epoch that the Alaskan dispute dates from. According to the Encyclopaedia, “after the decades of conventions signed in 1824 and 1825 [between Russia and Great Britain – Auth.], Americans and Brits alike, despite bitter confrontation around the Oregon Issue, kept on delivering new blows to ‘Russian America’ [Alaska, that is – Auth.]” ([85], Volume 2, page 205).

One still encounters Russian guests from America in the Muscovite Pokrovskiy Cathedral, on the Rogozhskoye Cemetery – from Alaska and Oregon. The younger generation is already incapable of speaking Russian for the most part, whereas their seniors usually speak Russian fluently enough. They are of the opinion that their ancestors have always lived in America and didn’t escape there after the schism of the XVII-XVIII century, as official history insists. Let us point out that official sources, be they Russian or American, demonstrate a great scarcity of information about the indigenous Russian populace of America. This topic is hushed up – deliberately, as we believe; otherwise, the consensual version of the history of America’s colonisation becomes a virtual can of worms and spawns an enormous amount of questions.

One might enquire about the following. If it is true that Siberia did not actually belong to the Romanovs before the defeat of Pougachev, how could St. Petersburg have sent the expedition of Bering in order to “discover” the Strait of Anian (soon to become Bering Straits)? Some surviving documents have kept the answer to this question – the expeditions of Bering were organised and carried out as secret affairs, especially the second, and there was hardly any information available” ([al2], page 347).

Moreover, the ensuing expeditions of Chichagov to the Kamchatka Peninsula, which took place in 1765-1766 were also considered “classified information” – top secret, in fact, since all reports of the expedition’s activity were to be kept secret “even from the Senate” ([al3], page 35). Also: “The first publications about these expeditions were made in 1793” ([al3], page 35) – already after Pougachev, that is.

Our opinion is that the reason behind such great secrecy was securing Russian priority in the discovery of lands previously unknown ([al2], page 347). However, we still encounter the same old temporal boundary of 1774 (the defeat of Pougachev). All Romanovian expeditions that predate it were top secret for some reason; the secrecy only disappeared after the victory over Pougachev. Our opinion is as follows. The expeditions of Bering, Chichagov and other Romanovian travellers of that epoch were military reconnaissance sent along the coasts of a neighbouring hostile country – the enormous Muscovite Tartary. Clearly enough, all information of this nature (reconnaissance, espionage and the like) was always kept secret – not simply from the enemy, but from the allies as well (even the Senate in this case). After the victory over Muscovite Tartary there was no reason left to keep the information secret, and so the Romanovs didn’t make any secret of the ensuing maritime expeditions.

Let us also note that the authentic journals of Bering’s expedition vanished, with nothing but their copies remaining intact ([al2], page 348). This is somewhat odd. In the epoch of the Romanovs, the originals of old documents constantly burn or vanish without a trace, unlike copies. Therefore, we are unlikely to find out about the initial content of Bering’s journals.

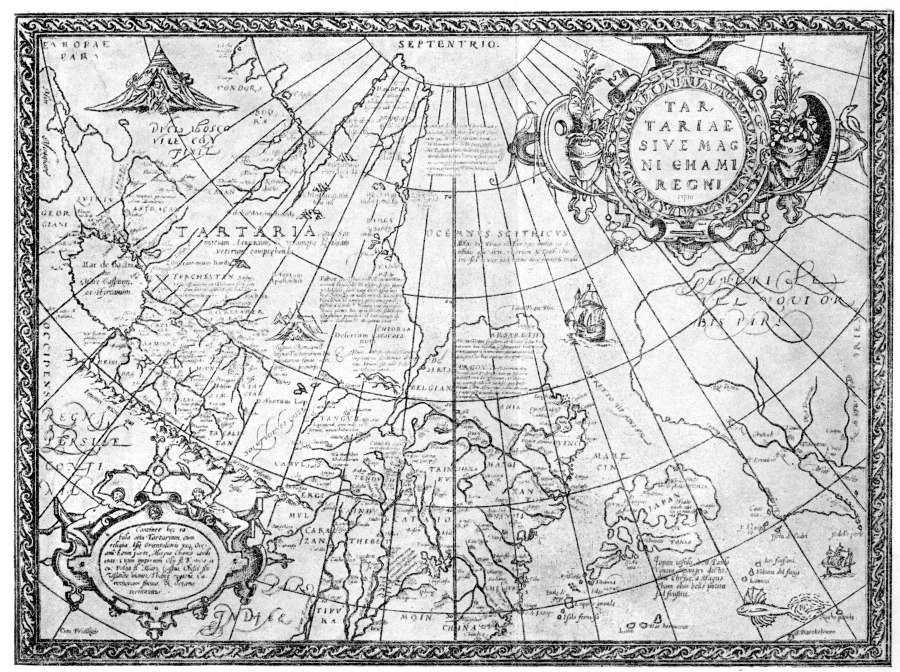

fig.14.28. Map of Great Tartary compiled by Ortelius in the alleged year 1570 A. D. (after L. Bagrov

The old name of the Bering Strait is very interesting – “Anian Strait”, qv in fig. 14.28. This is how the strait was called long before the “successful discovery” made by Vitus Bering in the XVIII century. Incidentally, the existence of the Land of Anian in the borderlands of Asia and America was even known to Marco Polo. Modern commentators are thus put in a very ambiguous position indeed. On the one hand, they may not allow for Polo knowing about the existence of any country in these parts, since they are certain that the itinerary of Marco Polo’s travels should be localised to latitudes that lay further to the South, the territory of modern China ([al2]). On the other hand, the text of Marco Polo is perfectly clear and understandable. Let us quote from L. S. Berg:

<<The name Anian should most definitely be traced back to Marco Polo, who mentions a province called Anin. In some manuscripts and editions . . . the fourth chapter of Polo’s third volume is followed by another, an obvious insert (although, according to Jules, it was possibly made by the traveller himself): “If we sail past the haven of Zaitum (or Zaiton) and sail Westward, and also some 1500 miles to the Southwest, we can reach the bay of Cheinan; the length of this bay equals two months of navigation, if one sails Northward alongside the coastline. This bay’s entire South-Western part washes the shores of the Manzi Province; the other part is adjacent to the provices of Ania (Amu, Aniu, and Anin in other manuscripts) and Toloman (Coloman in some sources). There are many islands in this bay; most of them are densely populated. They have a lot of golden sand – they pan for it in the estuaries of rivers. They also have copper, and other things galore . . . They trade with the mainland, selling gold and copper and buying whatever they need . . . This bay is so great, and it has so many inhabitants that it certainly seems a world apart>> ([al2], pages 15-16).

Marco Polo is clearly telling us about the Okhotsk and Bering Seas, which he calls the “Cheinan Bay” (Khan’s?). Further on, he clearly mentions the famous Kolyma (as Coloman); the land of Anian is located on the other side – it must identify as either Alaska, Kamchatka or both. It becomes obvious just why Polo emphasises the amount of gold panned for inside rivers. It is common knowledge that gold was panned for in the rivers of Kolyma and Alaska, and they pan for it in those parts to this very day, since there is a true abundance of gold in these parts.

Moreover, the Bering Strait, which separates Alaska from Kamchatka, was really referred to as Anian Strait on many ancient maps ([al2]), in full accordance with Marco Polo’s description of these parts. Thus, on the one hand, historians declare Marco Polo’s text to be fictitious, since he is supposed to have never visited these parts. On the other hand, everything that he writes corresponds to reality and to the ancient maps. At the end of the day, Polo may not have visited the Far North and the Okhotsk Sea; nevertheless, it is clearly obvious that his description is based on some XIV-XVI century documents originating from the Horde.

It is amazing how L. S. Berg disentangles himself from this situation, which is truly dire to any historian. He writes: “Doubtlessly, the Anian Strait is but a cartographic fantasy – an invention of Italian cartographers made in the second half of the XVI century . . . However, the fate of this cartographic myth is truly a wonder – it served as one of the reasons why Bering’s expedition set forth, discovering the Bering Strait right where the mythical ‘Stretto di Anian’ was located” ([al2], pages 23-24). No comments are needed here.

Our viewpoint makes everything perfectly clear. Marco Polo was describing the Great = “Mongolian” Empire. We have already written about it, qv in CHRON5, Chapter 14. It comprised East Siberia, Kamchatka and Alaska, as well as a wealth of other territories. Marco Polo uses the term “Province of Anian” for referring to Kamchatka, Alaska or both. Obviously, the strait between the two should be known as the Anian Strait, as discovered and reproduced on many maps of the Horde back in the epoch of the “Mongolian” Empire (many such maps became destroyed and forged later). Russians must have populated Alaska around the same time – in the XIV-XVI century.

Later on, after the decline of the “Mongolian” Empire in the XVII century, East Siberia, Alaska and a great part of North America became part of the new land with a capital in Tobolsk. When this country was defeated after the war against “Pougachev”, a rapid divide of its lands began between the Romanovs and the USA. However, for obvious reasons, the victorious countries (Britain and Romanovian Russia) were interested in presenting matters in such a way as though they were dividing lands that hadn’t ever belonged to anyone (this is how the Romanovs presented the annexation of Siberia and Central Asia). This has resulted in a number of oddities and obscure instances inherent in the consensual version of history. Just like the “embarrassing” (for both the USA and the modern Russia) presence of an indigenous Russian populace in America (Alaska in particular). There should be no such presence as per the laws of Scaligerian and Millerian history. But it carries on existing persistently enough, despite the glum taciturnity of the reference books and encyclopaedias. Our Russian guests from Oregon told us in 1996 that the indigenous Russian youth in America was taught in school that their ancestors were latecomers, and appeared much later than the British and French “pioneers”. Everything was different in reality.

Actually, traces of the name Anian remain in those parts to date. For instance, the indigenous populace of the Kurily Islands is called Ainu. A photograph of an Ainu called Ivan, no less, from Shikotan Isle, made in 1899, can be seen in figs. 14.29 and 14.30. We see a typically Russian face. In fig. 14.31 we can see an Ainu from Isle Hokkaido (Ieso). The face also looks typically Russian. According to the encyclopaedia, the Ainu are a “people facing extinction, which belongs to the initial inhabitants of Siberia . . . They inhabited most of Japan before the invasion of the Mongoloid race, and were almost completely destroyed by the latter in violent struggle” ([al4], Volume 1, page 174).

[al1] The “Encyclopaedic Dictionary” of F. A. Brockhaus and I. A. Yefron. St. Petersburg, 1898. Reprinted by: Polradis, St. Petersburg, 1994.

[al2] Berg L. S. “The Discovery of Kamchatka and the Expeditions of Bering” – Moscow and Leningrad, USSR AS Publications, 1946.

[al3] Berg L. S. “Essays on the History of Russian Geographic Discoveries” – Moscow and Leningrad, USSR AS Publications, 1946.

[al4] “The Concise Soviet Encyclopaedia”. – Moscow, Sovietskaya Entsiklopediya Publications, Volume 1, 1928.